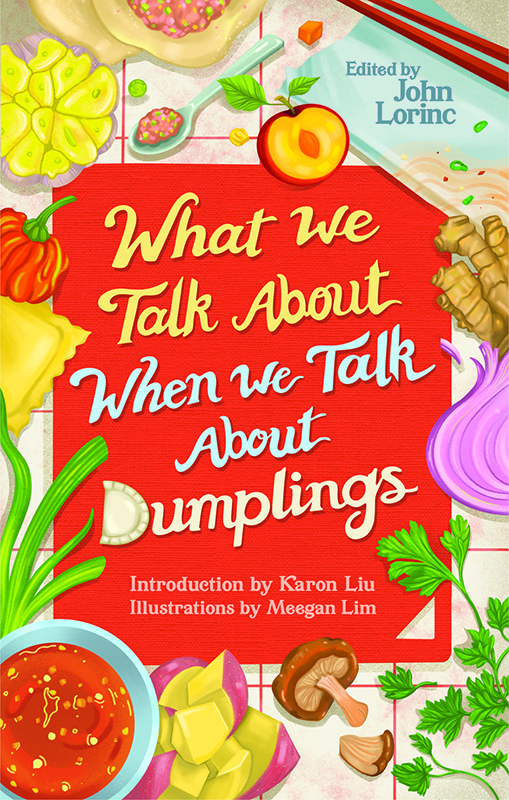

Unity, hope and food culture: new book featuring Toronto Metropolitan University’s alumni and instructors brings new meaning to dumplings

Depending on your ethnicity, your family's dumpling may be a tamale or a perogy, ravioli, shumai or har gow. In the new book, What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings (Coach House Books (October 2022), writers pay tribute to what they call a dumpling.

“Dumplings are a reminder that we all have more in common than we think,” one of the writers, Michal Stein, MJ’19, says.

The anthology, edited by John Lorinc, features essays by more than 20 writers, including Journalism at the Creative School alumni and instructors.

J-School Now spoke to some of the writers about the meaning behind dumplings and their essays.

“Ask No Questions About Samosas” by Angela Misri, Assistant Professor at Journalism at the Creative School

Misri’s dumplings are samosas and pakoras, but in her essay Misri also looks into conflicts between western culture in immigrant households.

What do ‘dumplings’ mean to you?

The only "dumplings" I had in my youth were pakoras and samosas. We rarely ate out (as immigrants in Calgary) so Chinese dumplings, Italian gnocchi, Ukrainian perogies, and all the other wonderful savoury-filled pastries didn't make it onto a plate in front of me till I moved to Ontario for school.

What can dumplings/or any of their variations teach us about representation?

Like many other things that unite different humans, we all love a tasty pastry filled with something savoury. It's something easily translated between cultures, "Try this, it's like your (insert local dumpling here to reassure the newbie)." Many of us have a shared relationship with family and making those dumplings.

What is a dumpling that represents the world of journalism?

I wonder if a matzo ball would be representative of fact-based journalism (and if they sink in their soup or taste like cardboard I hereby relegate them to fake-news)?

What is a dumpling that represents you?

It would need to be something surprising on the inside, so maybe a paneer pakora (a little unexpected and super-tasty).

In a world full of conflict and hopelessness, what symbolic message would you want to give through your writing in What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings?

That we're more alike than we are different and that many problems can be solved with a shared meal of tasty dumplings (I wish our political leaders would try it).

Why should people read this book?

Like a good dumpling, it is loaded with really tasty stuff (and even in small doses will satisfy your cravings).

“Around the World” by Michal Stein MJ ‘19 (she/her), Journalism at the Creative School alum

When Stein gathered friends for a “dumplings around the world” evening, she posted a photo of the delectables (external link) . She writes about the loss of one of her close friends, Julie-Rae King, and brings light to the unity of friends during and after a pandemic.

Why did you decide to contribute to What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings?

The editor, John Lorinc, reached out to me (after) my tweet about a Dumplings Around the World party I had with my friends went viral. People were reacting really strongly to my tweet, just on a surface level — getting in arguments about dumplings, getting excited or angry about our choices — but there was a much deeper story behind what we were doing, beyond the dumplings themselves, and I wanted to write about the road that brought my friends and I to hosting that party. I also loved the idea for the collection, and was really excited to be included among the other authors, many of whom I have admired for years.

What do ‘dumplings’ mean to you?

A dumpling is: a seasoned meat or vegetable, wrapped in a starch, then boiled, steamed, fried, or baked. You must be able to eat them in one or two bites. More broadly, dumplings are a reminder that we all have more in common than we think.

What can dumplings or any of their variations teach us about representation?

One thing we learned when we were planning our Dumplings Around the World party was that there were way more types of dumplings in the world than we could possibly fit on one table. It might take us years to get through all of them, and we will keep doing this annually until we've scoured every corner of the earth for dumplings and tried them all. Our project started with a realization, over dumplings, that every culture has their own dumpling. Of course, every culture's dumpling is different, and is so specifically tied to that region — but there is something universal about them. They're typically handmade, so they're a labour of love, but they're also typically made with inexpensive ingredients, so they're accessible. They're warm and comforting, but can also be a canvas for creativity — I once had a duck dumpling at Foxley on Ossington Ave. that blew my mind. One of our rules with our "around the world" dinners, where each person brings a different dish, is that there's no one winner — we're all winners, because we all get to enjoy an abundance of beautiful food. I think dumplings kind of follow that rule — they symbolize abundance, almost an expansiveness in possibility. There doesn't need to be a hierarchy — which one is best, what's the Platonic form of dumpling — because as long as you're eating dumplings, you're doing pretty well. Again, I think dumplings serve as a reminder that beneath all our differences, we have a lot in common with each other.

What is a dumpling that represents the world of journalism?

This is a bit controversial, because a calzone is more of a pocket than a dumpling... but I would have to say a calzone, which represents the boxes of pizza delivered to newsrooms everywhere on election night.

What is a dumpling that represents you?

In an ode to my 96-year-old grandmother, who would hate that I wrote about eating shrimp and pork dumplings (we're Jewish, and shrimp and pork are not kosher), it would have to be her perogen, which I was lucky enough to have with my chicken soup over the High Holidays this year. Perogen, as she makes them, are similar to Polish pierogies, but the dough is a bit different, and we typically eat them in soup. Honestly, it might just be pierogies, but in Yiddish. She usually makes them with meat, and they're always a hit. After a disappointing encounter with kreplach (which I wrote about in my essay), I am firmly on Team Perogen as far as Jewish dumplings go. Many would argue that a matzo ball counts as a dumpling, but if we get started on that conversation, we're going to be here all night.

In a world full of conflict and hopelessness, what message would you want to give through your writing in What We Talk About When We Talk About Dumplings?

I ultimately wanted to talk about the power of community when dealing with challenging situations. A year and a half into the pandemic, my friends and I found ourselves dealing with a tragedy we never could have expected. We all had to do a lot of growing up, really fast, and figure out how to support each other and stay afloat. The path of least resistance for this is always food. How do you support someone going through a hard time? Bring them dinner. Leave it for them if they want to be alone, or stay if they're open to having company. Dumplings are the perfect vehicle for this kind of connection. If you get dumplings by yourself, you can really only have one kind of dumpling, maybe two. If you get ten of your friends together? Now, you can have ten different dumplings. So I guess my message is – the world doesn't have to be so hopeless when you share the load with other people.

Why should people read this book?

The whole book is delightful. I'm amazed at the kinds of connections other writers were able to make in their thinking about dumplings — there's stories of self-discovery, explorations into family lineage, and a few recipes thrown in for good measure. If you're ready to forever change the way you see dumplings, read this book, because by the end of it, you'll realize that dumplings are so much more than just spiced meat or vegetables, wrapped in starch, then boiled, steamed, fried, or baked.

“Patty Controversy” by Dr. Cheryl Thompson (she/her), Assistant Professor, TMU’s School of Performance

In her chapter, Dr. Thompson writes about Jamaican patties and how it came from one place, arrived in Canada and was kept alive as it represented its own Jamaican culture, while sharing western cultures.

Why did you decide to contribute to What we talk about when we talk about dumplings?

John Lorinc, editor of the collection, was my editor on my second book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty (external link) . He is also an editor at Spacing (external link) , where I contribute a column on race, space, and culture in Toronto. So when he approached me asking if I would write about Jamaican patties, I jumped at the idea given the previous experiences we have working together, and his understanding of my approach to writing cultural histories like this one.

What do ‘dumplings’ mean to you?

As I said in a recent CBC Magazine interview (external link) , dumplings are a universal street food in so many cultures because of their simplicity -- a meat or veggie encased in a pastry. This culinary treat is literally enjoyed in a plethora of variations in every region of the world. For me, dumplings symbolize home, comfort, and community.

What can dumplings/or any of their variations teach us about representation?

They teach us the universality of food and the ways in which differences in terms of race, ethnicity, language and even culture, when you boil it down to the bare bones, are the things in this world that make the world worth living in. The idea that in Poland they're eating perogies while in China they're eating dim sum, etc. but at the core they're both essentially eating the exact same food with its regional nuances and variations says a lot about the universality of cultural experiences and history.

What is a dumpling that represents you?

In the book, I wrote about Jamaican patties. While not traditionally considered a dumpling, the argument I make is that it's a street food born of a diasporic experience of transatlantic slavery, immigration, and place-making. Like so many food cultures in Canada, it came from somewhere else, and arrived here with a people who not only kept the tradition alive but with the opening of shops and restaurants, shared that food with the cultures of the Western world. For me, a dumpling, like a patty, represents a culture from "over there" that has found itself "over here".

Why should people read this book?

The reason they should read any book -- to learn something new about something they think they know but likely have little context about its historical development and also the profound meaning this particular food has for people around the world.

Other School of Journalism alumni and instructors who contributed essays to the anthology include: Karon Liu, Chantal Braganza and Navneet Alang.