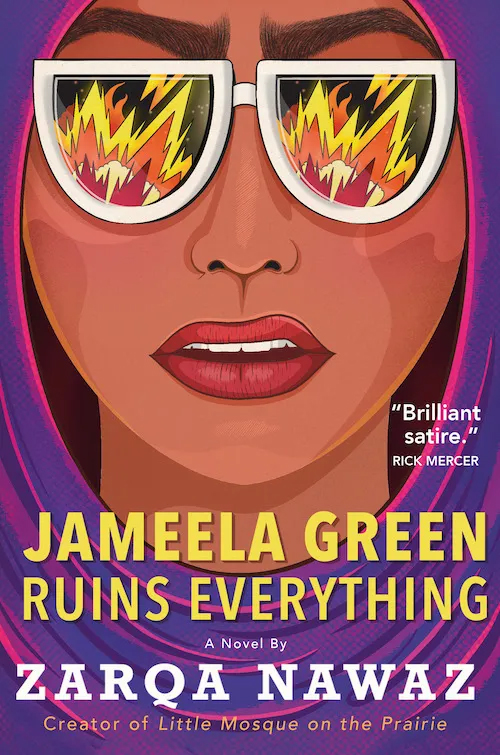

Q&A with alumna Zarqa Nawaz on her satirical novel Jameela Green Ruins Everything

Zarqa Nawaz, ‘92, released a satirical novel this year, Jameela Green Ruins Everything. She is an accomplished producer, author, public speaker, journalist, and former broadcaster. Best known as the creator and producer of the award-winning CBC TV sitcom Little Mosque on the Prairie, which addressed the stereotypes and misconceptions about Muslims.

She is a trailblazer known for her zesty, distinctive, searing satire, which she envelopes in every piece of work that she creates. This book is no different, as Nawaz does not shy away from uncomfortable topics like war, terrorism and selective empathy.

If you could summarize the experience of writing this book into one line, what would that be?

Writing this book was a very long, exhaustive [laughs] and ultimately rewarding experience.

This book has been years in the making, what was the original idea for Jameela Green Ruins Everything?

I remember going through a lot when my first book (a memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque (external link) ) had been published and feeling a sense of, “I wish the book had done better,” and “I wish the book had been a bestseller.” I felt like a professional failure as an author. At the same time, ISIS had just emerged in the media, and it had been a really painful and difficult time for Muslims. The popular media were saying things like, “Well, this is what ultimately Muslims do: gravitate towards Jihad and become jihadists.” I wanted to understand the forces behind what created this group. So, I created a character who was going through a really difficult emotional and spiritual time … and that somehow she gets embroiled in a terrorist group, which she brings down through incompetence.

It was my way of understanding what was going on in the world and understanding what was happening with myself emotionally at the same time.

What were some of your favourite comedians/sources of comedy growing up that informed your approach?

I grew up on a diet of CBC Radio, and the satire of This Hour Has 22 Minutes — all those radio comedies that were exclusively on CBC Radio. I feel like those political satires really informed me growing up.

Unpacking political issues can be a daunting task. But you manage to add a satirical lens when discussing complex and nuanced issues, making them a bit more approachable. What do you think it is about comedy that keeps people listening?

A lot of people have tried to figure out what it is about comedy. Personally, I think when you laugh, you let down your guard and you acknowledge the humanity of someone else in a way that you normally would not do if it was very serious, and you were being lectured to. When you laugh, you kind of let your defenses down. That chink in the armor allows you to think about something in a new, novel way that maybe you had not considered before.

In an article (external link) about the book, you said “My hope is that when people read my novel, they get a greater understanding of how actions in one part of the world, albeit well-meaning, can have catastrophic results for another people that can last for generations.” Can you explain what this means in the political context of writing this book?

When we see, say, the issue of Ukraine, I see all these really sympathetic and empathetic stories. There are so many stories, night and day, about the suffering of the Ukrainian people, and rightly so, but those stories were missing what happened to the people in Iraq, after weapons of mass destruction had gone into that country and destroyed it. I feel that there was this lack of empathy towards Muslims, because we are not really seen fully as humans. So, when I see and read stories about Ukrainian people and how much the media is worried about their suffering I wonder, if those stories had existed when the bombs had fallen in Iraq, would they ever have fallen in the first place?

We are willing to give one group of people all our empathy and support, and for another group of people, it seems like it doesn't even matter what they are going through - there is a double standard. The Iraqi and the Syrian people suffered the same way for much longer, and it was allowed to happen because there was this sense that they deserved it. The antipathy towards the Middle East brings home the fact that you can have large areas of the world that suffer for a long period of time because people assume that brown and black people are used to suffering. So what's the big deal? Whereas white people are not used to suffering. The only way I could bring this issue to light was by writing about it. A lot of people who read my book are like, "Wow, we had no idea. We really had no idea.”

From what I understand, publishers weren’t too keen on the book at first, but that didn’t stop you. Then you get a book deal and a TV series deal in one day. Can you describe what that moment was like as creative in this industry?

The arts is a really tough industry to be in for anyone, and then not to be white, it is even harder when you are going against the stream of what is acceptable. The work that I do tends to go against what a lot of people in this industry focus on. We are talking about a secular kind of world of art where they prefer secular stories, and I write a lot of stories that are very much faith based.

Then I get criticism from some Muslims themselves, who feel that I am too liberal and wanting to change the faith or making fun of it, and not having a level of sophistication that you need to be able to understand satire. Satire is not necessarily making fun of faith, but showing people their own insecurities, agendas and racism in a different light. I think sometimes Muslims cannot see that they tend to be very binary. So, I tend to get two groups of communities who really do not like my work and that is how I feel like I am doing something right.

You do not want everyone to love you, because that means that you have diluted your work to such a degree that nobody really cares that much about you. If you can irritate people in just the right manner, then you have struck a nerve.

If there is something that you would want a reader to think about, what would that be?

We should look at injustice equally for all people of all colours, races and religions and not just for the people who look the same as us. That is what I would want people to leave thinking about. Also, to really be more curious about stories in the Muslim world and to read more stories written by Muslim authors from their perspective.

What are your next projects?

CBC has greenlit the second season of Zarqa (external link) ! I also have a comedy with CTV in development called Bad Muslims, which is about a heist in the mosque during Ramadan.

For students in the journalism program who would like to follow a similar path as yours, what would be your advice?

To really have a point of view that is authentic to your voice and not be afraid of it. I know that sometimes means it might be taking a longer and harder journey, but in the end, it is worth it. You cannot follow the trends, you have to make the trend out on your own and have the courage to do it. It is hard - I am not gonna lie, it is really, really hard, but I think that is what the world needs: people who have the courage of their own convictions and speak truth to power.