INNOVATION

Issue 43: Fall 2025

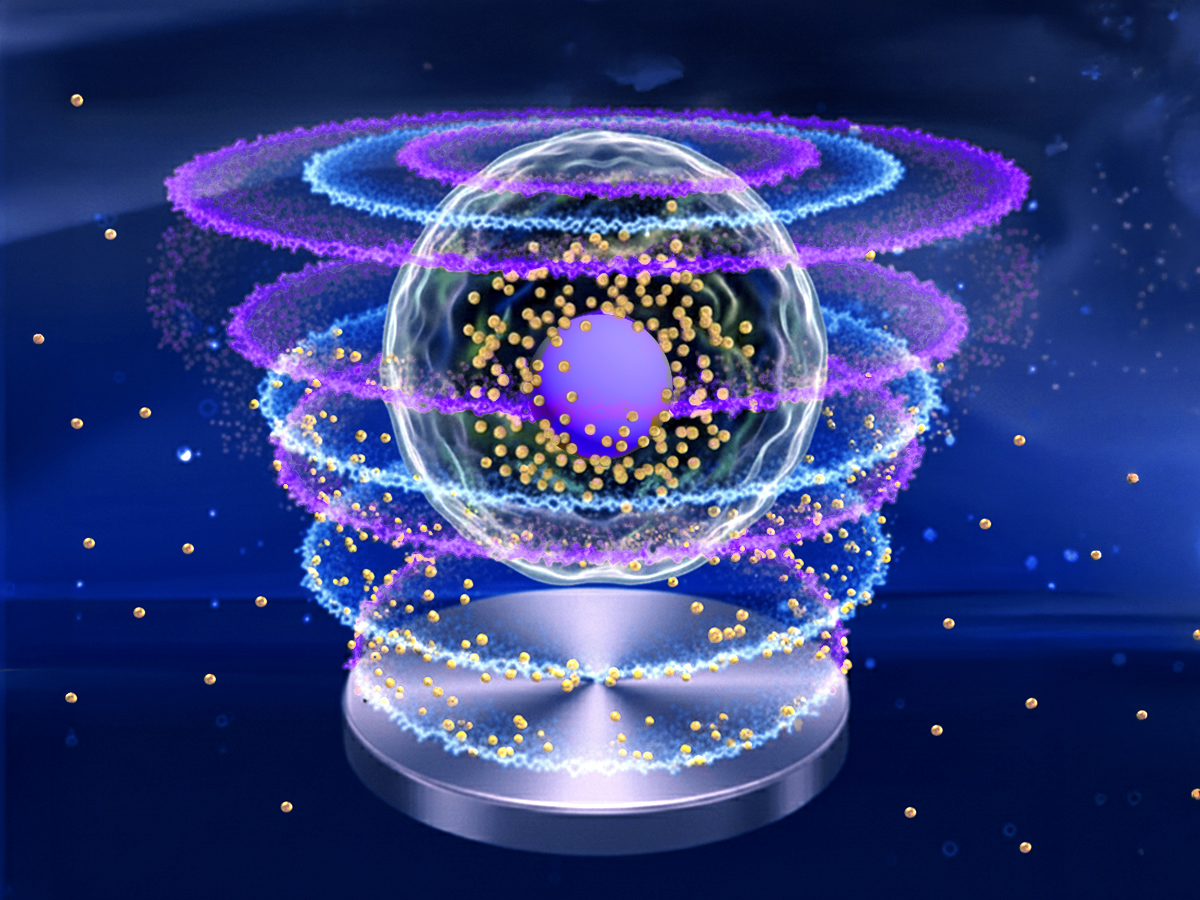

Combining ultrasound waves with nanomedicine to treat cancer in a new way

Idea to Innovation

Combining ultrasound waves with nanomedicine to treat cancer in a new way

A novel combination of two treatment methods has yielded a promising advancement in targeted drug delivery for cancer therapy, according to the Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) team behind the research.

Their work shows that using low-intensity ultrasound waves to activate drug-coated gold nanoparticles inside the human body can deliver a higher dose of tumour-fighting drugs where they’re needed most.

Using gold nanoparticles to treat cancer isn’t a new idea – it’s been extensively explored for more than a decade. The minuscule particles are coated with chemotherapy drugs and injected into the body to attack tumours. Still, efficient targeting has been a challenge, in part because human cell membranes and the tumour microenvironment act as barriers to effective drug uptake.

Likewise, while it’s been known for years that ultrasound is able to influence what happens inside cells, the exact ways it affects cellular behaviour – such as how cells respond, communicate or process drugs – are still not fully understood.

However, as the TMU work shows, when unfocused, low-intensity ultrasound waves are used to activate drug-coated gold nanoparticles inside the body, the outcome is a new, synergistic drug delivery platform with “a significant improvement in pre-clinical treatment efficacy,” according to the team’s paper in Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.

Multidisciplinary project flourishes in integrated research environment

This unique combination of ultrasound and nanomedicine was developed at the Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology (iBEST), a partnership between TMU and St. Michael’s Hospital, a member of Unity Health Toronto. The project has united researchers with expertise in physics, engineering and computational modelling, as well as hospital clinicians and researchers.

“It’s an incredibly multidisciplinary effort,” said project supervisor and TMU physics professor Michael Kolios. “It brings together ultrasound physics, chemical synthesis, and tumour and cellular biology, all converging toward clinical application. The iBEST environment makes this kind of integrated research possible.”

A key member of the TMU research team is Farshad Moradi Kashkooli, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Banting postdoctoral fellow in TMU's Department of Physics.

“Non-invasive strategies to improve drug delivery efficiency are really needed,” Moradi Kashkooli said. “This is a very safe, non-invasive method to enhance cellular drug uptake.”

The treatment is delivered with a transducer, a device that emits the low-intensity ultrasound waves. Those waves help a greater number of nanoparticles – each so small that their width is about one ten-thousandth of a single human hair – to pass through cell membranes and deliver their drug payload.

The drug-coated gold nanoparticles used in the research were created in the team’s TMU labs by postdoctoral fellow Anshuman Jakhmola. Likewise, the handheld transducer used to deliver the ultrasound waves is also a TMU creation: it was developed by the late professor Jahan Tavakkoli, former chair of the Department of Physics.

Why using low-intensity ultrasound is important

The low-intensity ultrasound waves enhance nanoparticle and drug uptake at the cell level in two ways. The first is thermal, with ultrasound waves heating the cells and increasing their permeability. The second is mechanical, further increasing permeability and allowing more drug-coated nanoparticles to enter.

In tests performed on triple-negative breast cancer cells, the researchers were able to target a larger area for treatment while also limiting potential damage to surrounding healthy tissue.

“With focused ultrasound, the treatment zone is about the size of a grain of rice,” professor Kolios said. “At lower intensities, we can control the size of that zone, making it as small or as large as needed. The effect occurs only where the gold nanoparticles are located within the region exposed to the low-intensity ultrasound, leaving surrounding tissues unharmed.”

Professor Kolios praised the accessibility of the TMU-designed, handheld transducer used in the research.

“It’s simple, it’s portable,” he said. “You don’t need costly equipment, like MRI-guided systems, that focused ultrasound often relies on. This device can achieve therapeutic effects in a more accessible way.”

Read the paper, "Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances uptake of doxorubicin-loaded gold nanoparticles in cancer cells (external link) ,” in Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.

It’s an incredibly multidisciplinary effort. It brings together ultrasound physics, chemical synthesis, and tumour and cellular biology, all converging toward clinical application.

The research described in this article is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Ontario Research Fund and Toronto Poly Clinic Inc.