M.Arch Students Nicola Caccavella, Kavita Garg, and Julianne Guevara Win First Place in Manhattan Wildscaper Competition

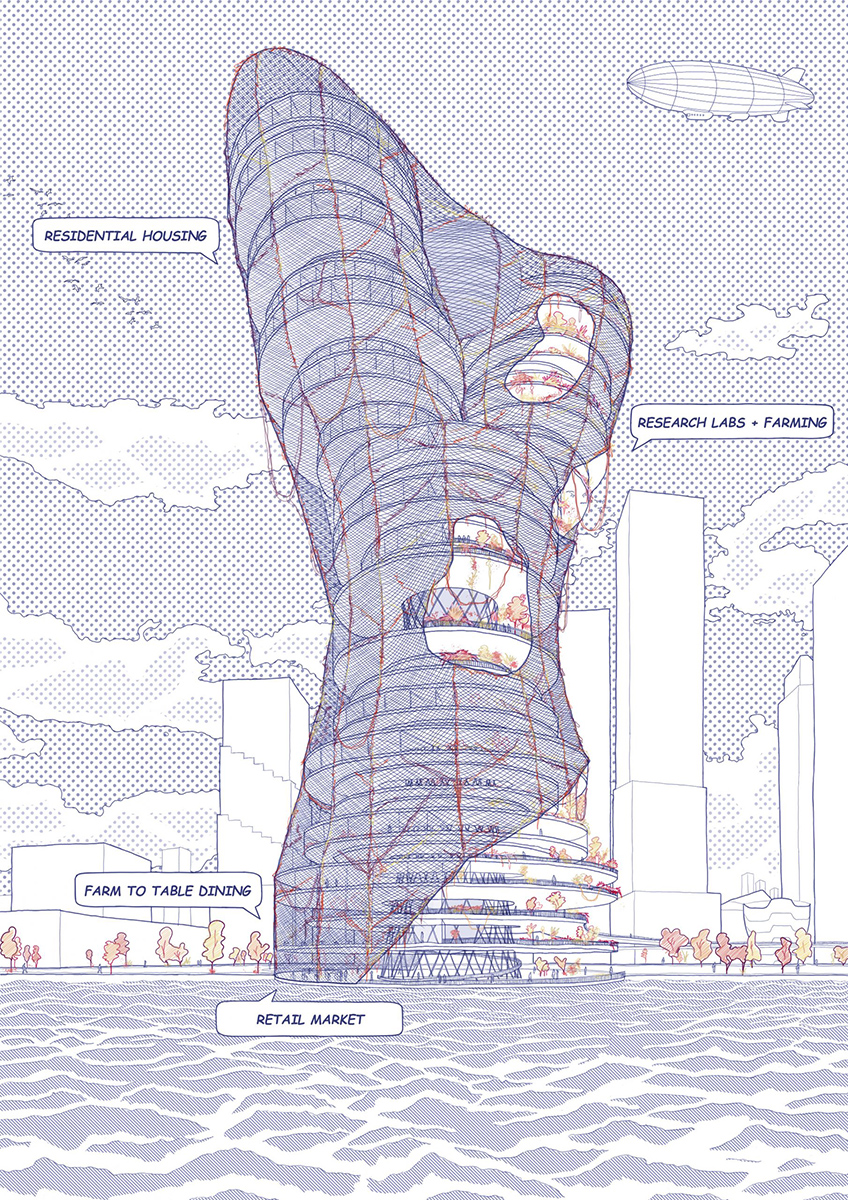

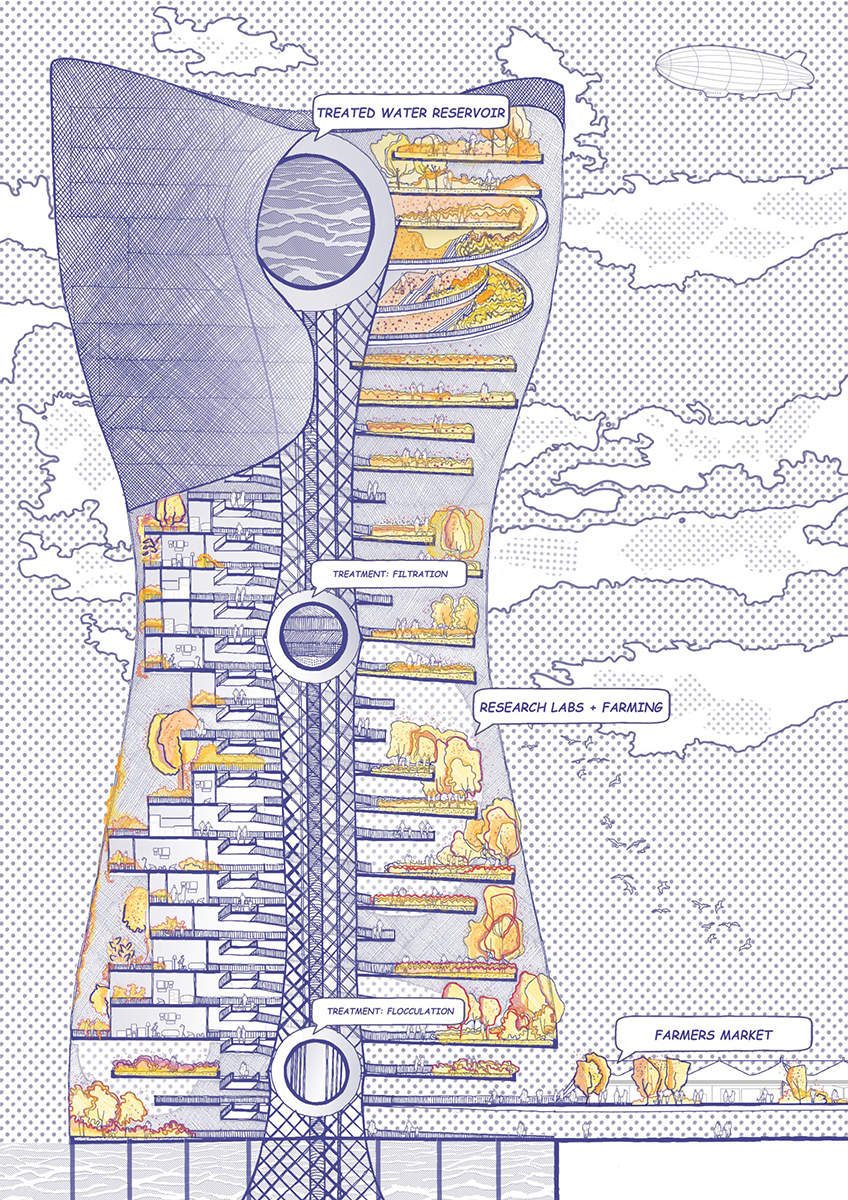

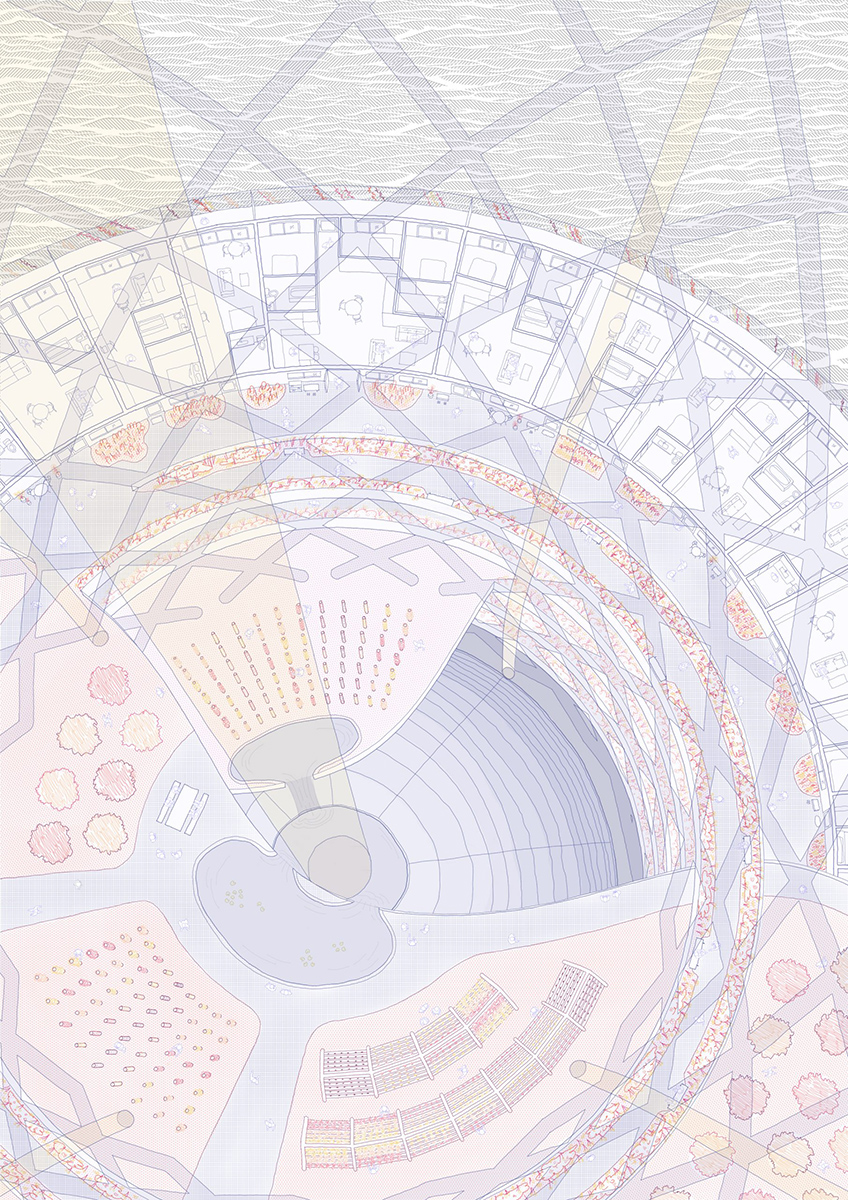

One of two grand prize-winning entries, Nicola, Kavita, and Julianne worked together to develop three drawings for the "Living Water Tower", a mixed-use, green skyscraper which places emphasis on the filtration and purification processes of air and water located in the Hudson Yards (external link) . The building is situated at the original terminus of the High Line, which would extend through the interior of the tower, spiralling upwards. While it incorporates a traditional program (retail, residential, and commercial), it does so unconventionally. The building separates into two parts, one tower which houses on-site research laboratories and farming, and another containing residential units embedded within greenery. The farm sustainably grows crops which are easily transported and utilized in the farm-to-table dining and retail market on lower floors.

Nicola: We’re all in our second year of the MArch program, and I had a great experience as an undergraduate student here. One of my interests that makes its way into all of my work (and I think this goes for all of us), and something I’ve learned is important to incorporate aspects of, is the relationship between the built environment and community.

Julianne: This competition really gave us the opportunity to essentially do anything we wanted, and it challenged us to communicate our ideas in just three drawings. It allowed us to be highly conceptual in our approach as well.

Kavita: As someone based in Mumbai, I really like the brief because it has very attractive components: for example, the drawings allow for the exploration of abstract ideas without being very specific. Another aspect I liked was the emphasis on the integration of people with nature, which I feel is very important. Julianne and I had already explored the concept in one of our studio projects, this notion of giving agency to nature--instead of humans having agency over nature, how can humans adapt to nature? The competition gave us the opportunity to explore a kind of landscape where people from different backgrounds - whether they farm, work in the markets or are residents, can interact with nature.

What aspect of the competition resonated with you the most?

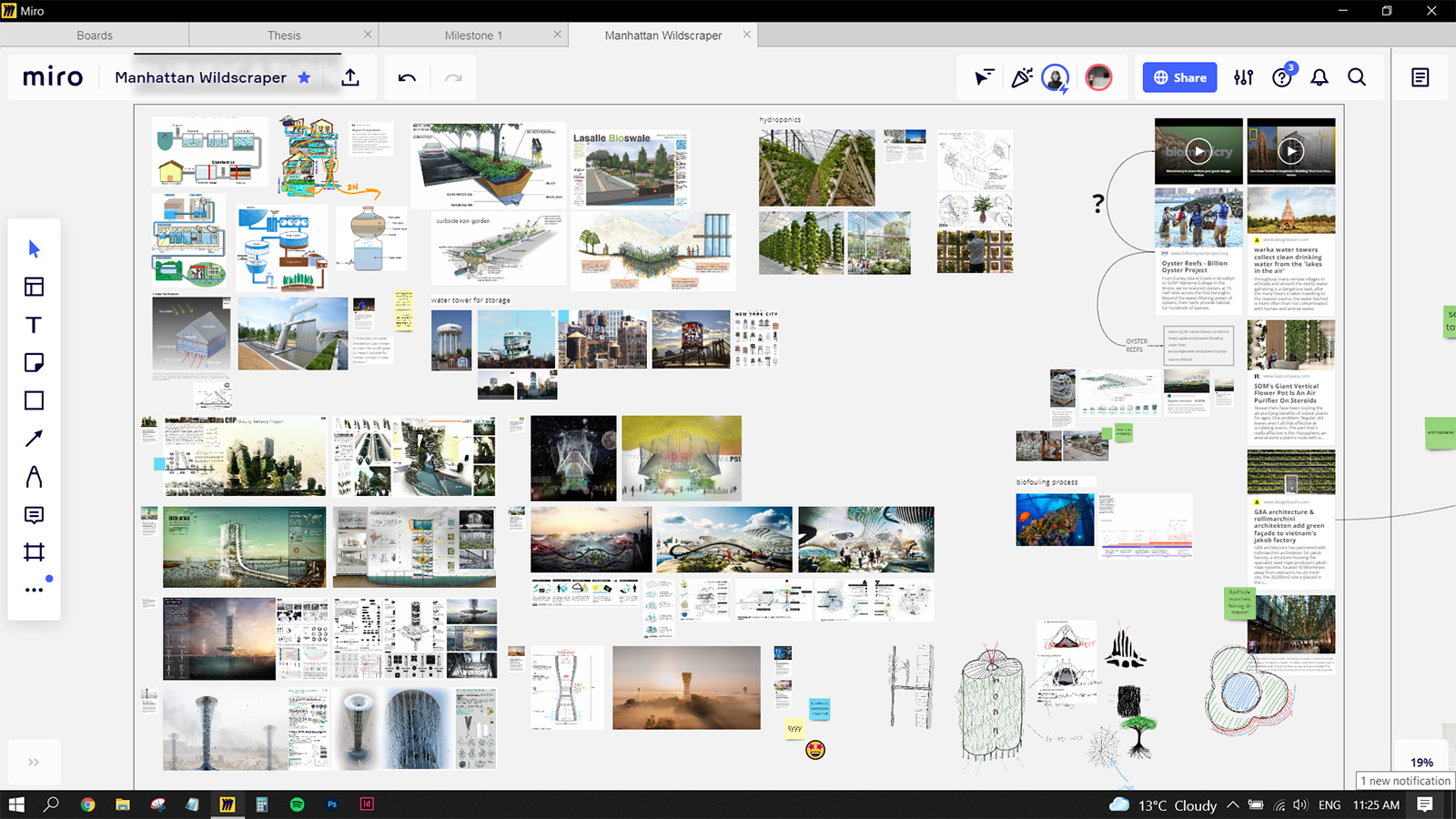

N: The project deals with the relationship between architecture and biodiversity - integrating the natural and built realm. I'm interested in biomimicry - that's what inspired a lot of the work. We incorporated the natural distribution of water through the netting which was inspired by spider webs; we looked at the Coanda effect - the ventilation of heat through the stack effect as well as Murray’s law for the structure - all of these things made their way into the design.

K: The MArch program itself is an important platform for us to develop our values. I’m still developing those values, but they include community and cultural integration, and Canada itself is very diverse and is now becoming more aware of its own colonial past. This really resonates with me because I am also from a colonial nation, and so I see the competition as a platform to respond to that diversity. I also think giving agency to things which are inanimate or things you cannot quantify as important, is part of decolonization. We made a conscious effort to not get into those more controlling details, but to expand on larger ideas of how the high line (even though it's so horizontal) expands and becomes vertical in our proposal. It gives us the flexibility to break the barriers of the known and question certain systems by bringing about unknowns.

J: Yeah, the ability to be free and expressive.

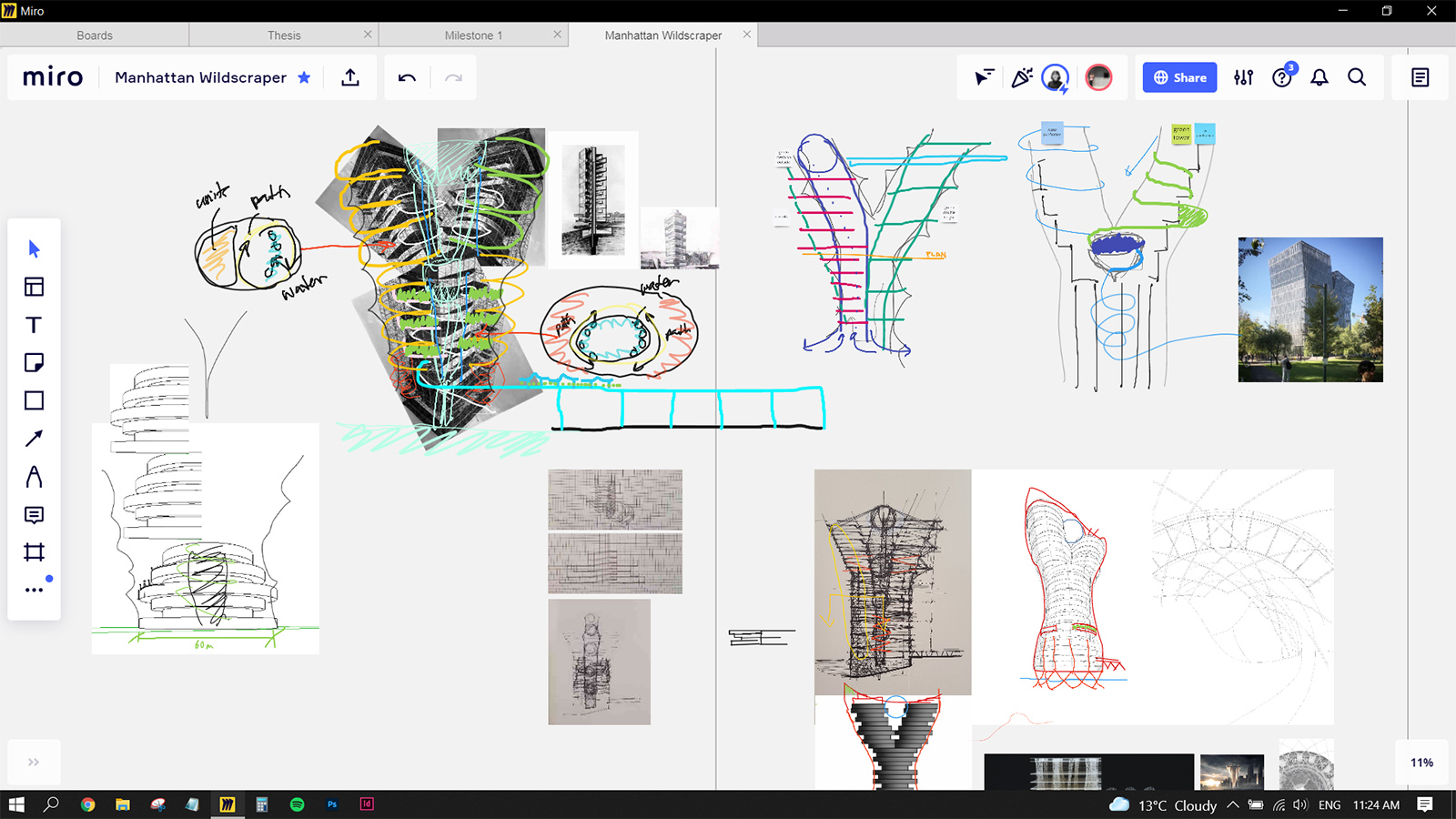

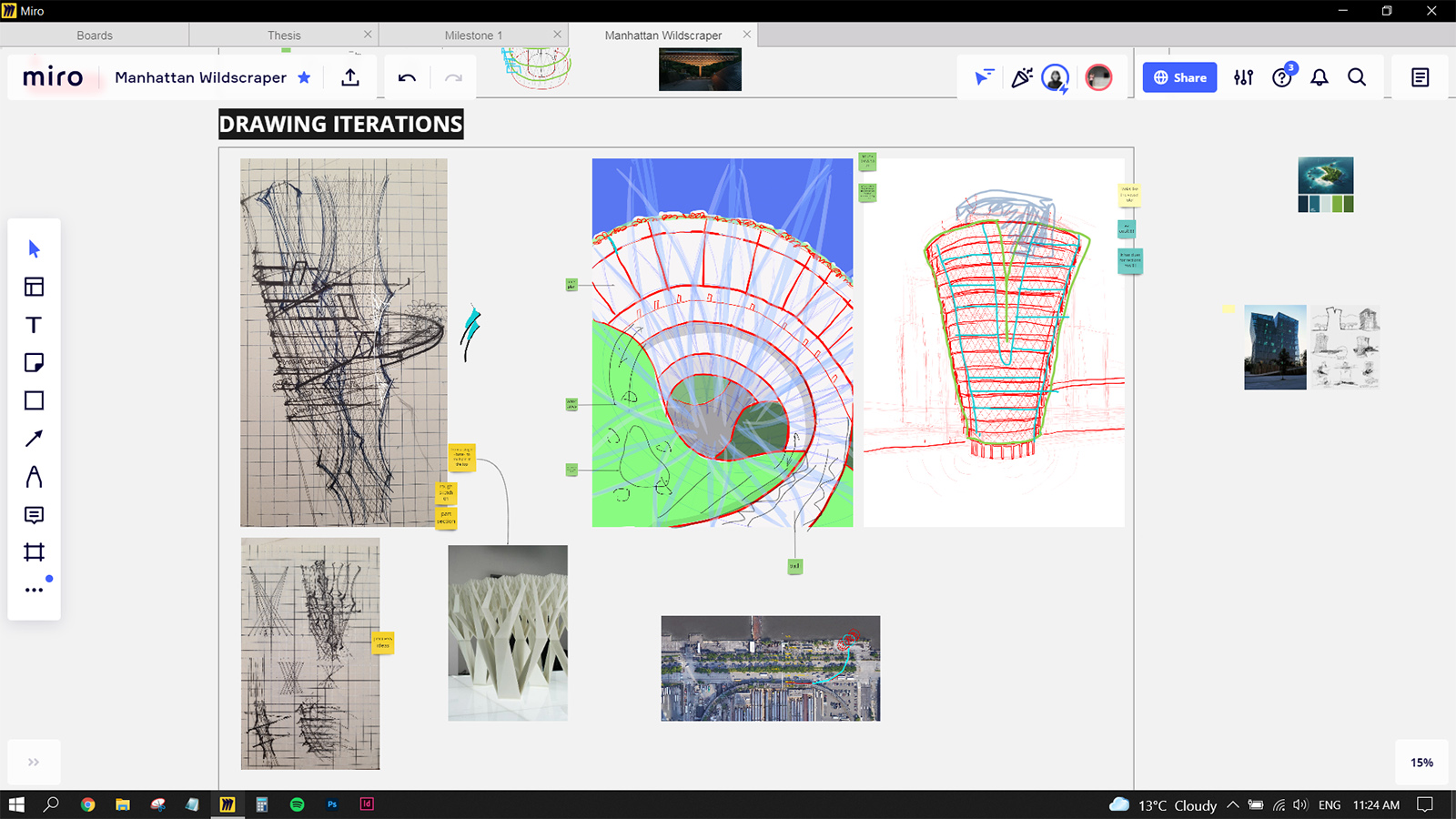

N: Also the fact that there wasn’t pressure to produce digital drawings. We decided to hand draw everything, and when we’d meet, we would draw over each other’s drawings which really added to that free, collaborative aspect.

K: Sometimes working on digital models means you can lose that touch of drawing with your hands. This approach really taps into the intuitiveness that we sometimes tend to lose when we work on digital models.

N: We would put our drawings on miro, and then we would draw over them.

Can you take us through why you chose the Hudson Yards as your site in Manhattan?

N: The Hudson Yards is important, and is a neighbourhood that is still being developed. It’s split up into what’s been developed with the vessel and those buildings. It’s highly capitalistic. We thought it would be Interesting to use the High Line to direct our building to the other end of the road - and to have the building give back to the natural element of New York, to combat these capitalist forces. The extension of the High Line ended up coming naturally from that.

When we finished the project, I visited New York a few weeks after. Even when you look at it from The Vessel, you can see all these clean and polished buildings around you. Given where our building is located, if you were to turn around and look at our building from The Vessel, it wouldn’t be so clean and polished, as it’s something that integrates the built and natural form.

J: The project also focused on water as a resource and our relationship with water - we wanted to find a site on the river. It’s a perfect point of tension in thinking about how we can integrate water into the building. Water purification was a really central aspect to the project: the building flows over the water a bit and really interacts with it there. Interacting with the river ecosystem was another important point for site selection.

K: The Hudson Yards is an increasingly commercialized space, and as a result it’s becoming less accessible. As it gentrifies and caters to the upper classes, it excludes marginalized communities and those who don't really fit into those systems. We are trying to rupture that point of being closed off from the rest by extending the High Line, by having a messy building, by integrating nature and water, and we are trying to open up that particular junction to more people.

N: Drawing on my own real world observations of this place, I noticed that while the area is new and densely populated, there aren't as many people as you would expect to be there. There are thousands of people living in these buildings but all of these public spaces feel deserted.

K: When my parents visited the area, they noticed that the malls and the shops in that area were priced for wealthy people. It speaks to the kind of people who would use that area, so introducing something like a farmers market, we think would open up the space to more people.

N: I didn’t even go into the shopping mall, I noticed that it looked fancy. The NY Times also published an article about Hudson Yards as Manhattan’s biggest gated community. So we thought, “Okay, it would be good to choose that site and do something completely different from what already exists there.”

Can you speak to how sustainability is a crucial part of urban fabric?

K: Everything is interconnected. Sustainability is something we’ve been talking about for the last two decades because of climate change. I also think that by responding to growing social disparities, you can actually respond to climate change. As architects we always have to keep in mind we cannot respond to things on the macro level, we have to respond through design, through buildings - so we try to do this by coming up with systems of integration, integrating nature and people, and making things more accessible for everyone. By responding to such themes, we are already responding to sustainability and climate change. It’s a slow process but we are stuck in this kind of profession of optimism. By doing small interventions, by responding to things on the micro level, we would be experiencing some changes 20, 50 years down the road on the macro level.

N: Like Kavita says, everything is intertwined. If you're talking about environmental sustainability, you’re also talking about social sustainability. As the climate changes, it affects people's lives elsewhere (for example, coastal cities). We’re always hearing about this many people forced to leave their homes. Everything is connected: the social, the economic, and climate sustainability. Everything is connected but on different scales. I think In order to tackle climate change, you have to look at it from all these different spatial and temporal scales.

Can you speak to your design process a bit more?

J: I think from the very beginning, we distilled our objectives into major themes: the duality of nature, water purification and agriculture cultivation. We established these goals early on. Then we would put each of our drawings beside one another every week and sketch over them to be on the same page conceptually, stylistically, and tectonically. Some of the things that may not be immediately evident from the drawings is our research into a lot of purification systems and vertical agriculture, and how to facilitate ecosystems. We had a fun time working on everything.

N: We also had guidance from Will Galloway who was our supervisor for the competition. He really helped us pull everything together into this one cohesive building. Also as a practicing architect, he almost brought it to real life, because he was looking at how things work at the street scale, and how to funnel people into the building. Before that, we were just looking at the themes. His mentorship really helped us transform these concepts into a building.

Tell me more about why you chose to display the drawings in comic book format.

N: It was partly due to being inspired by some other drawings, and how we wanted to represent the building. The hand-drawn approach also lent itself to that style.

J: Yeah, since we were already doing the drawings by hand, the comic book aesthetic and labeling methods really worked with the drawings we already had.

N: The history behind comic book design and how it was largely inspired by Hugh Ferriss really opens up this correlation between architecture and comic design.

How has being students at DAS helped you approach this challenge?

J: I can really see the connection between my two stages of education at DAS - our undergraduate program is very technical and detail focused. There is emphasis placed on understanding how things are going to stand and be put together. Going into the masters, it's almost the opposite - projects can be super conceptual, and you’re free to propose anything you want. So I think our project brings that together - even though it’s this wild proposal, there’s still a rationale to it, a logic to it. You can really see the structural elements of the building being expressed, and this holistic integration with the city. So, as we are developing the design, we have that foundation to build off of to do something that’s wild but that also makes sense.

N: It’s a kind of organized chaos, because there’s a kind of structure behind it even though it may not be as apparent.

K: Speaking as an international student, the freedom to think very conceptually is something I love, and at the masters level I think it’s important to have that freedom because ultimately - you can build things, but you have to be the person who can think through things too, and that’s what DAS encourages. With our first studio assignment, our professors would say that even if a project takes you in a direction that doesn’t result in a building per se, that’s fine - as long as the work forces you to think through things that wouldn’t otherwise be talked or thought about, either because it’s too controversial or challenging to current norms. It lets me be an international student who can respond to something which I am not aware about, it helps me bring my lived experience into something which is extremely new.