Edmonton: Proactive Planning + Modest Financial Burdens + Greenfield Development + Existing Neighbourhoods Densification = A Housing Affordability Miracle

By: Frank Clayton, Senior Research Fellow

October 29, 2025

(PDF file) Print-friendly version available

Executive Summary

Edmonton's housing market is now the envy of other Canadian cities, with housing starts increasing significantly over the past year and a half, and its reasonable housing affordability. Compare this to Toronto, where housing starts are plummeting and housing remains extremely unaffordable. The conclusion remains the same regardless of whether the comparison is between the two central cities or their metropolitan areas.[1]

This blog examines new housing production in metropolitan Edmonton by unit type and location, and the reasons behind these developments. Lessons from the Edmonton experience for housing supply and affordability in metropolitan Toronto are drawn.

Key Finding

Metropolitan Edmonton demonstrates that it is possible to produce a considerable amount of new housing across a range of housing types in response to strong demand, while maintaining affordability. Metropolitan Toronto, unfortunately, lacks the preconditions to create a similar housing outcome. The onus is on the province to oversee fundamental changes in metropolitan Toronto's governance and planning regime if overall affordability is to be effectively addressed. This requires, among other things, appropriate policy changes and infrastructure investments to support shovel-ready development.

The Edmonton experience: lessons for metropolitan Toronto

- Recognize, plan for and implement actions to accommodate a full range of new housing at the metropolitan Toronto level, particularly ground-related and missing middle housing;

- Recognize the need for differing primary roles of built-up areas (apartments) and greenfield areas (ground-related housing) in contributing to the full range of new housing;

- Simplify and expedite the land use approvals process to make it more responsive to the needs of the metropolitan housing marketplace;

- Set a target for intensification and redevelopment in built-up areas, not exceeding 50% at the metropolitan level, rather than for individual municipalities;

- Significantly reduce the costs imposed on new residential development by municipalities by financing infrastructure through full-cost user charges for sewer and water services, contributions from senior governments, and property taxes rather than through development charges and community benefits charges; and

- Implement at least annual monitoring of municipal short-term land inventories to ensure the metropolitan area always maintains an ample supply of shovel-ready sites across a range of housing types, thereby stabilizing land costs and promoting competition in the development industry.

Introduction

Edmonton's housing market is now the envy of other Canadian cities, with housing starts increasing significantly over the past year and a half, and housing is reasonably affordable. Compare this to Toronto, where housing starts are plummeting and housing remains extremely unaffordable. The conclusion remains the same regardless of whether the comparison is between the two central cities or their metropolitan areas.[2]

We begin by comparing housing starts in the Edmonton metropolitan area and its components (the city of Edmonton and the suburban municipalities combined) using CMHC starts data by unit type for 2023 and 2024. Our focus then shifts to the city of Edmonton, where building permit data by unit type are examined for developing (greenfield) and redeveloping (built-up) areas.[3] Next, we recap the reasons for Edmonton's housing supply and affordability miracle. Finally, we examine the lessons of the Edmonton experience for housing supply and affordability in metropolitan Toronto.

This blog is a follow-up to a previous post that examined why housing is significantly more affordable in the metropolitan areas of Edmonton and Calgary than in Toronto.[4] That blog concluded that the benign affordability in the two Alberta metropolitan centres was the result of (a) a plentiful supply of shovel-ready greenfield lands and intensification and redevelopment sites in built-up areas, and (b) a housing-conducive planning system that encouraged missing-middle housing and lower financial burdens on new development.

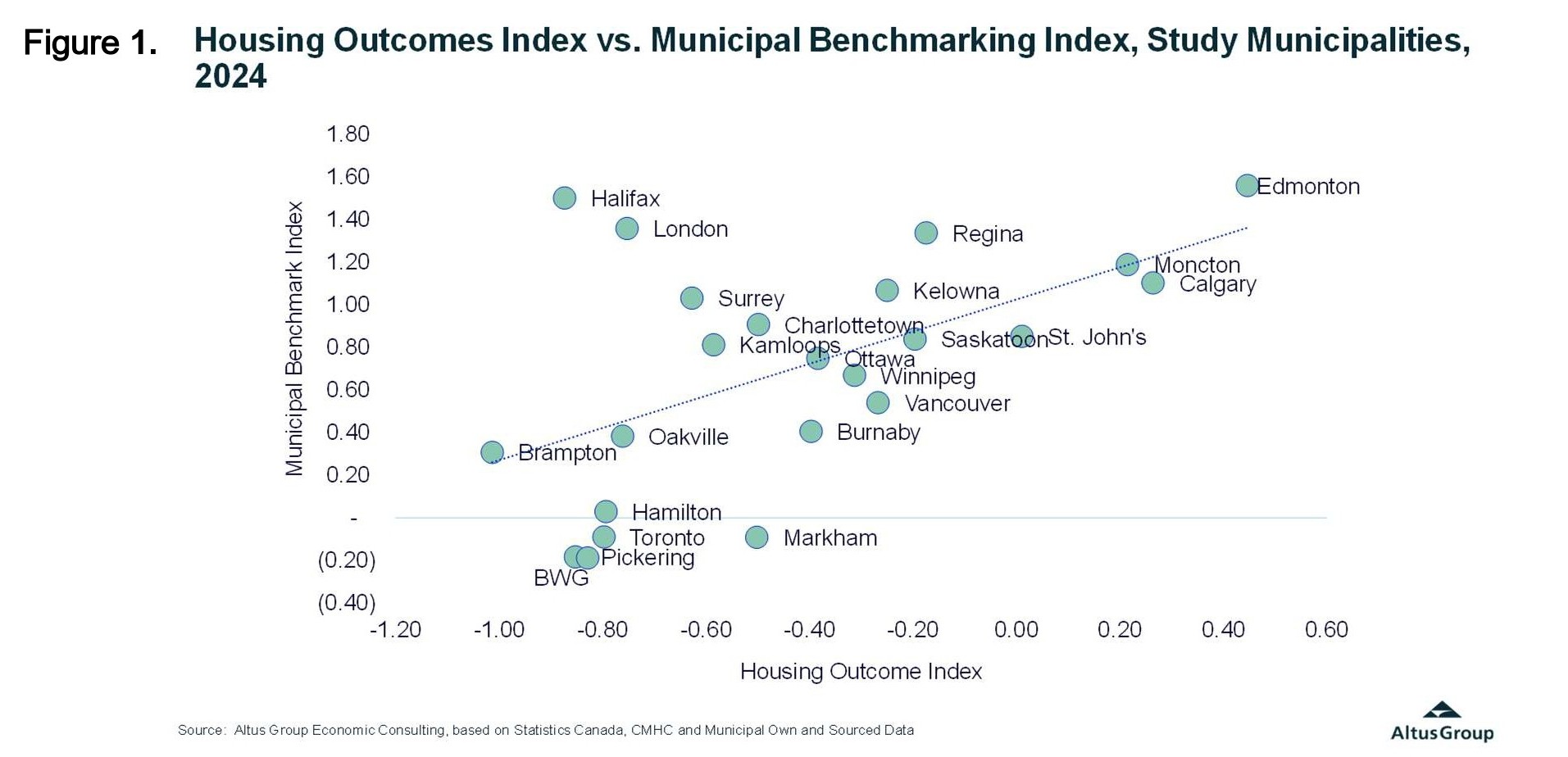

Edmonton is Unique

According to a recent Altus Group study, the city of Edmonton is unique among the 23 municipalities surveyed (see Figure 1).[5] Not only does it rank highest (best) in the most favourable housing outcome index (housing affordability and availability), it also ranked highest (best) in the municipal benchmarking index (lower municipal fees and shorter approval timelines).[6]

Compare the Edmonton ranking with that of Toronto and other municipalities surveyed within the metro Toronto area, which are ranked the lowest (worst) in both the housing outcomes index (housing affordability and availability) and the municipal benchmarking index (municipal fees and shorter approval timelines).

Metro Edmonton: Housing Starts by Type

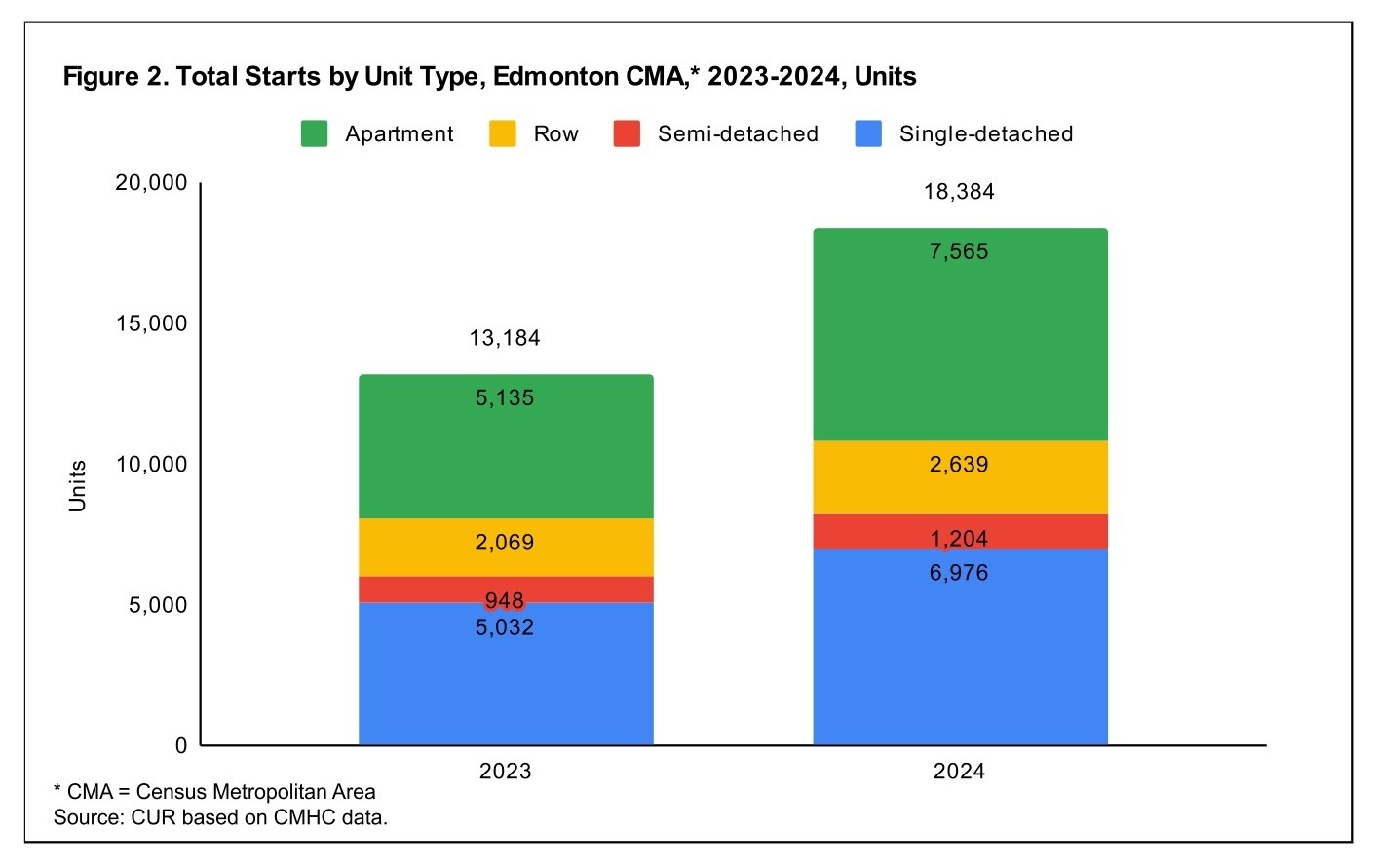

Figure 2 shows housing starts in metro Edmonton by type of unit in 2023 and 2024.

Housing starts surged in Metro Edmonton in 2024

Total starts in metro Edmonton jumped by 39% from 13,184 units in 2023 to 18,384 in 2024.

The 2024 surge in Metro Edmonton starts was due to apartments and single-detached houses

Both apartments and single-detached houses contributed to the significant increase. Apartments climbed by 47% and single-detached house starts by 39%.

Ground-related housing accounted for the majority of the metro starts

Unit types other than apartments (referred to here as ground-related housing[7]) accounted for 59% of total starts in metro Edmonton in 2024, down slightly from 61% in 2023 (Figure 2). The apartment share increased marginally from 39% to 41%.

City of Edmonton vs the Suburban Municipalities: Housing Starts by Type

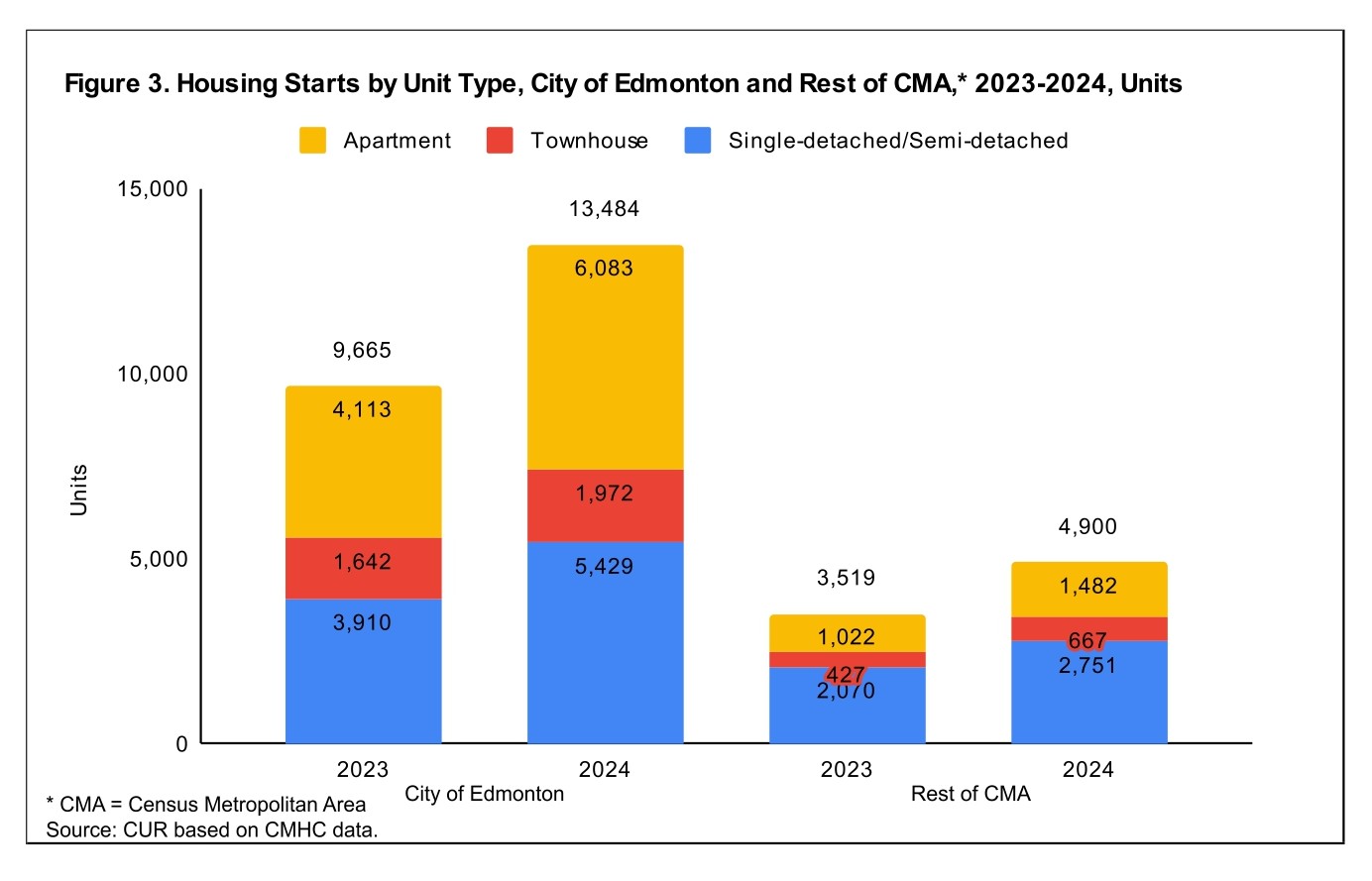

Figure 3 breaks down the housing starts in Metro Edmonton by unit type, distinguishing between the City of Edmonton and the suburban municipalities.

The city of Edmonton is the primary location of housing across the housing type spectrum

Aided by a plentiful supply of greenfield land, the city of Edmonton outperformed its neighbours in all types of new housing, as enumerated by CMHC, including singles/semis and townhouses. It also dominated apartment construction. The city accounted for 75%-80% of the 2024 starts of single-detached/semi-detached houses, townhouses, and apartments.

City of Edmonton vs the Suburbs: Apartment Starts by Intended Tenure

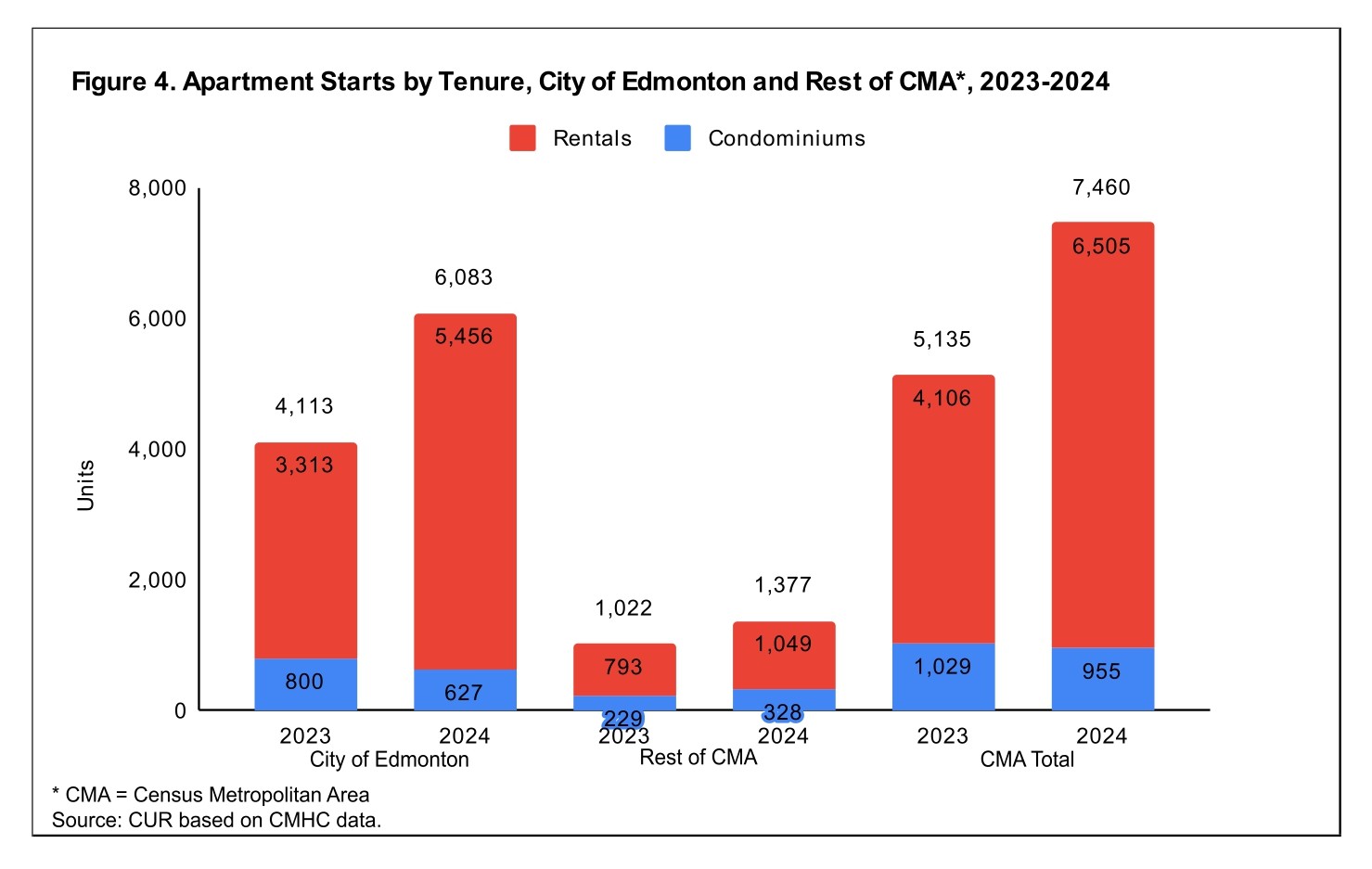

Figure 4 splits apartments starts in metro Edmonton between units intended for the rental market (purpose-built rentals) and those intended for the condominium market.[8]

Most of the new apartments in metro Edmonton are purpose-built rental

Most apartment starts in the metropolitan area in 2023 and 2024 are in buildings intended for the rental market, both in the city and its suburban municipalities.

City of Edmonton New Housing: Greenfield and Built-up Areas

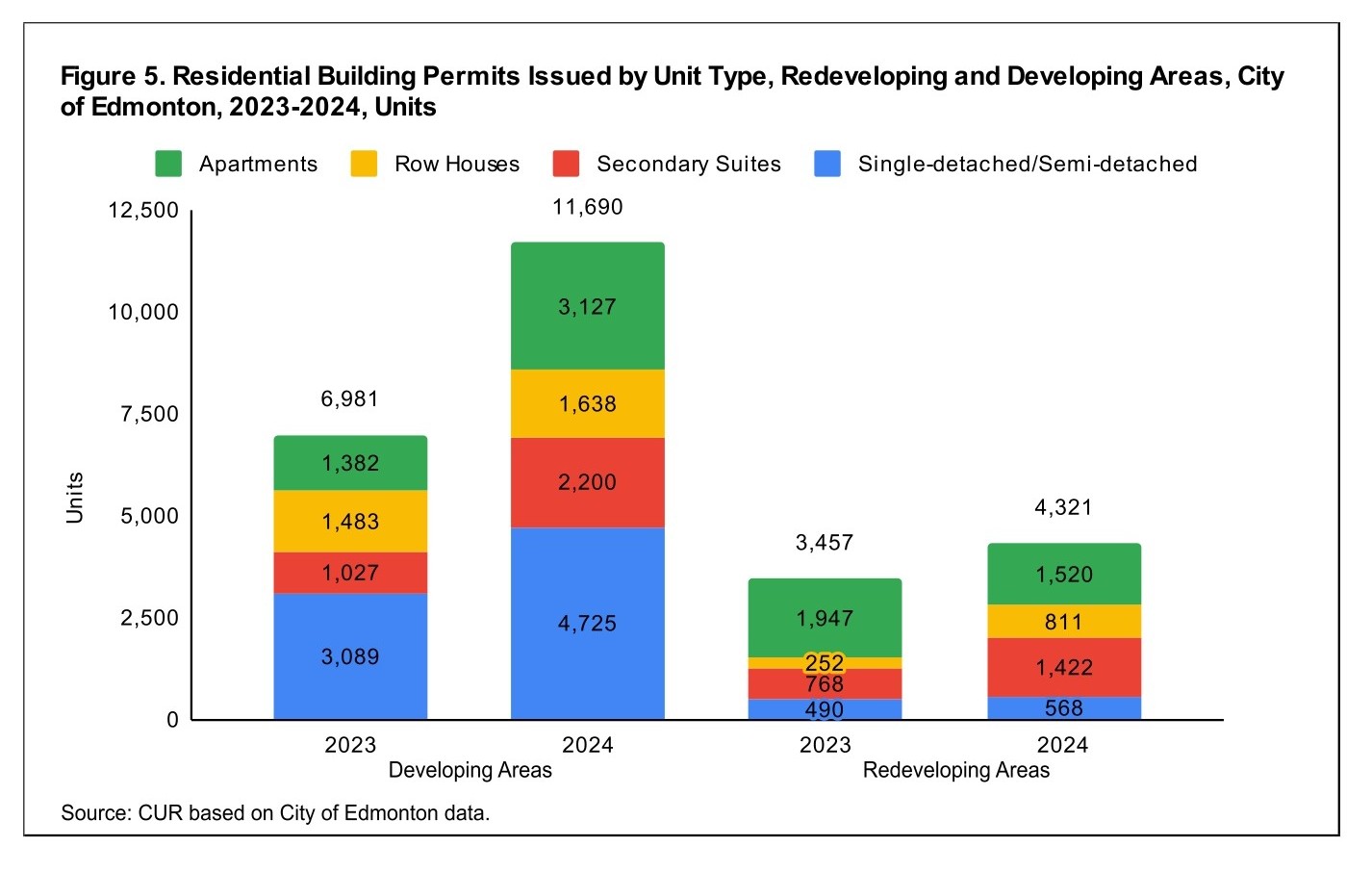

Figure 5 presents new housing building permits by type for greenfield areas (developing areas) and built-up areas (redeveloping areas) in the city of Edmonton in 2023 and 2024. Single- and semi-detached houses are combined. The city data separates secondary suites from other apartments.[9]

Apartments accounted for the majority of new housing in built-up areas, about equally divided between secondary suites and units in apartment structures

In 2024, the new housing in the city's built-up areas (redeveloping areas) included a variety of unit types, with apartments in apartment structures making up the largest component (35%), followed by secondary suites (33%) and townhouses (19%).

Greenfields accommodate a broad mix of housing

In 2024, the housing built on greenfield land (developing areas) included more than just single and semi-detached houses. Singles and semis accounted for 40% of all new units, while apartments (excluding secondary suites) made up 27%, townhouses accounted for 19%, and secondary suites accounted for 14%.

Greenfields accommodates the majority of each type of new housing in the city of Edmonton

Figure 5 shows that:

- Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the new housing built in the city of Edmonton in 2024 was built in a greenfield area – up from 55% in 2023;

- The greenfield areas accounted for the majority of each housing type; and

- More secondary suites were created in newer houses in greenfield areas than in existing houses in built-up areas.

Key Attributes of Metro Edmonton's New Housing Market Performance in 2024

Summarizing what we have discovered:

- Metro Edmonton recorded a surge in housing starts in 2024, mainly the result of increased rental apartment and single-detached housing starts;

- The city of Edmonton dominates the metro area's new housing supply across all unit types;

- The majority of new housing in the city is accommodated on greenfield land;

- A wide range of housing types are built on greenfield lands; and

- Surprisingly, there are more secondary suites built in new houses on greenfield lands than are added to existing houses in the built-up area.

How is Metro Edmonton Able to Achieve Its Housing Affordability Miracle?

Let's now examine the factors underlying Edmonton's achievements in housing supply and affordability. The focus is on the city, as it dominates the metro market across all housing types. It is worth noting that both Toronto and Edmonton have rapidly growing populations. Here are our findings.

Municipal boundaries encompassing most of metropolitan Edmonton's housing activity

The production of new housing is facilitated when there is a single or dominant municipality in a metropolitan housing marketplace, according to a previously published research report comparing the metropolitan Toronto and Ottawa housing markets.[10] As we have seen, the city of Edmonton accounts for 75-80% of all new housing constructed in the metropolitan area, across all housing types. In metropolitan Toronto, in contrast, the city of Toronto accounts for the majority of apartment starts but has few ground-related housing starts.

Regional municipal coordination

Until recently, planning for metropolitan Edmonton was undertaken at the regional level by the Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board.[11] The Board's mandate included planning for and promoting a range of housing options.[12] Metropolitan Toronto lacks a regional planning body to coordinate growth, including infrastructure and housing.

Planning for the long-term future

Edmonton comprehensively plans for the future. The City Plan, approved by the City Council in 2020, envisions the city growing from approximately one million to two million people.[13] The goal is to build 50% of new housing units in the built-up area through infill. The remaining 50% will be built in greenfield areas. Progress toward achieving The City Plan's goals is monitored through Annual Growth Monitoring Reports.

Although the city had a sizable 71,529 vacant lots for single- and semi-detached houses in approved greenfield areas in 2023, it annexed 8,260 hectares from Leduc County and the City of Beaumont in 2019 to accommodate long-term urban growth.

The city has been at the forefront of encouraging what it calls "infilling" of its built-up area. Starting with permitted secondary suites in existing houses, its efforts culminated in its comprehensive zoning bylaw overhaul effective January 1, 2024. The bylaw allows a maximum of eight dwellings per lot in the R5 zone (Small Scale Residential Zone), the most common zone in Edmonton's mature neighbourhoods.

Accommodative planning process

Land-use regulation and approval times in metropolitan Edmonton are rated more favourably than in high-cost areas such as metropolitan Vancouver and Toronto, according to a 2022 survey by CMHC/Statistics Canada. Overall land-use regulation was estimated to be 18% less onerous, and approval delays were 50% lower than in metropolitan Toronto.[14] An Altus Group study concluded that the city of Edmonton had the sixth-fastest approval times and the best planning features among 21 Canadian cities surveyed in 2024.[15]

Moderate municipal charges

The city of Edmonton also imposes relatively low financial charges on new residential development. The Altus Group study, conducted in 2024, estimated that the municipality had the lowest government charges among the 21 surveyed.[16]

Monitoring residential land availability and future infrastructure needs

The city of Edmonton produces annual reports on low-density residential lot absorption and supply, as well as infill approvals in redevelopment areas.[17] It also prepared 10-year forecasts of the city's infrastructure requirements.

In 2024, the city had 68,240 remaining potential planned and developing lots for single- and semi-detached houses in approved greenfield areas (Area Structure Plans and Neighbourhood Structure Plans).[18] Of these, 37,348 lots were available for development (within developing area neighbourhoods with approved Neighbourhood Structure Plans). According to city planners, these lots are sufficient to support demand up to The City Plan's 1.5 million population threshold.

Lessons from Edmonton for Housing Availability and Affordability in Metropolitan Toronto

The stars have aligned for Edmonton, making it the poster child for housing supply and affordability among Canadian metropolitan areas experiencing substantial growth pressures. What is needed to recreate the Edmonton miracle in Toronto? It is recognized that metropolitan Toronto’s circumstances differ significantly from Edmonton's, including population size and absolute growth, the lack of greenfield land in the central city, and physical and regulated constraints on potential greenfield expansions.[19] However, the metropolitan Edmonton experience offers guidance on expanding housing supply by unit type and improving affordability.

- Recognize, plan for and implement actions to accommodate a full range of new housing at the metropolitan Toronto level, particularly ground-related and missing middle housing

Metropolitan Toronto no longer has a shortage of shovel-ready high-rise apartment sites. Much more action is needed to increase the short- and medium-term supply of shovel-ready land for ground-related housing—single-detached, semi-detached, and townhouses—and reasonable close substitutes, such as duplexes, stacked townhouses, and low-rise apartment buildings (so-called ‘missing middle housing’). Surveys consistently show that the majority of households prefer ground-level housing or as close to the ground as possible.

Since the city of Toronto no longer has greenfield sites and, in the absence of a metropolitan-wide governance structure, the Province must take the initiative through regulation, restructuring, or incentives.

- Recognize the differing primary roles of built-up areas (apartments) and greenfield areas (ground-related housing) in contributing to the full range of new housing available

The economics of site and housing development are such that apartments will be the dominant type of housing built in built-up areas, with a component of townhouses. In contrast, ground-related housing will be more common in greenfield areas with a component of apartments. The challenge is to introduce a significant number of missing-middle housing units in both areas to improve affordability.

Greenfield development in metropolitan Toronto is, in fact, providing a range of ground-oriented and missing-middle housing types. The drive to densify existing low-density neighbourhoods needs to be more aggressive, allowing for higher densities in the form of townhouses and apartments to make redevelopment more financially viable.

- Set a target for intensification and redevelopment in built-up areas, not exceeding 50% at the metropolitan level, rather than for individual municipalities

Currently, provincial planning directives in Ontario require municipalities to establish and implement minimum targets for intensification and redevelopment within their built-up areas, but they do not specify these minimum targets.[20] These targets are applied at the local municipal level. Failing to recognize that all new housing in the fully developed cities of Toronto and Mississauga is on intensified or redeveloped sites can lead to exaggerated targets in other municipalities within the metropolitan area.

- Significantly reduce the costs imposed on new residential development by municipalities by financing infrastructure through full-cost user charges for sewer and water services, contributions from senior governments, and property taxes, rather than through development charges and community benefit charges

Municipalities have become accustomed to charging developers the costs of building or improving infrastructure, thereby substantially increasing the base costs of new housing construction.

A fundamental change is required in the way infrastructure is funded. For utilities like sewer and water, a shift to a full-cost pricing model would eliminate the need for funding through development charges. The provincial and federal governments are financial beneficiaries of the new development and should be funding infrastructure more generously than they are presently.

- Require and enforce at least annual monitoring of short-term municipal land inventories to ensure the metropolitan area always has an ample inventory of shovel-ready sites across a range of housing types to stabilize land costs and promote competition in the development industry

The city of Edmonton regularly monitors its residential land supply and takes action to ensure an ample inventory of sites for new housing. Metropolitan Toronto, in contrast, lacks an equivalent land inventory database, despite a provincial directive requiring municipalities to maintain a minimum of a three-year supply of short-term land by unit type at all times (with a minimum of four years' inventory and annual monitoring).

Following the housing affordability crisis of the late 1980s, the housing industry, along with federal and provincial governments, funded consultants to prepare an annual inventory of residential land in metropolitan Toronto, a practice that continued until 2003. The province and the industry should reactivate this initiative.

Conclusion

Metropolitan Edmonton demonstrates that it is possible to produce considerable new housing across a range of housing types in response to strong demand, while maintaining affordability. Metropolitan Toronto, unfortunately, lacks the preconditions to create a similar housing outcome. The onus is on the province to oversee fundamental changes in metropolitan Toronto’s governance and planning regime if overall affordability is to be effectively addressed. This requires, among other things, appropriate policy changes and infrastructure investments to support shovel-ready development.

End Notes

[1] Metropolitan areas refer to census metropolitan areas as delineated by Statistics Canada. The terms metropolitan area and metro area are used interchangeably.

[2] A metropolitan area (census metropolitan area, or CMA) as defined by Statistics Canada approximates the regional housing market, as it encompasses the areas where most people work and live. “Metro area” is used interchangeably with “metropolitan area” in this paper.

[3] Edmonton city planners refer to greenfield lands as developing areas and built-up areas as redeveloping areas.

[4] Frank Clayton. “The Globe & Mail is Correct: Ontario Can Learn About Housing in Alberta But Disregards the Importance of Greenfield Development.” CUR blog. November 22, 2024.

[5] Individual municipalities were surveyed. The city of Edmonton was the only municipality in metro Edmonton surveyed.

[6] Altus Group. “Municipal Benchmarking 2024 Study.” Prepared for the Canadian Home Builders’ Association. March 2025. The housing outcome index is based on four variables: housing affordability, suppressed households, rental vacancy rate, and out/in migration (p. 61). The municipal benchmarking index is based on three variables: approval timelines, municipal charges and fees levied on new residential development, and planning features used to facilitate more efficient and transparent development processes (p. 1).

[7] Ground-related housing is the sum of single-and semi-detached houses and townhouses.

[8] Condo-registered apartment buildings are intended to accommodate owner-occupants but investors can own and rent out individual units.

[9] CMHC and the Census of Canada categorize houses with a second suite as a duplex unit. The city of Edmonton classifies the house as single-detached, semi-detached or townhouse with the secondary suite classed as such. Backyard housing is combined with secondary suites here.

[10] Frank Clayton. “The Housing Affordability Benefits of Commutershed Land Use Planning: A Case Study of the Ottawa and Toronto Metropolitan Areas.” CUR. February 6, 2024.

[11] Madeleine Cummings. “Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board votes to initiate process for winding down operations.” CBC News. Last updated: January 23, 2025.

[12] Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board. “Growth Plan Overview.” November 2021.

[13] City of Edmonton. “The City Plan.” Office Consolidation June 2025.

[14] Referenced in Frank Clayton. “The Globe & Mail is Correct: Ontario Can Learn About Housing in Alberta But Disregards the Importance of Greenfield Development.” CUR blog. November 22, 2024.

[15] Referenced in Frank Clayton. Ibid.

[16] Altus Group. “Municipal Benchmarking 2024 Study.” Prepared for the Canadian Home Builders’ Association. March 2025.

[17] Edmonton realizes the importance of collecting land inventory data by unit types.

[18] City of Edmonton. "Low Density Residential Lot Absorption and Supply." 2024 Annual Report.

[19] The constraints are Lake Ontario and the greenbelt lands.

[20] Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. “Provincial Planning Statement, 2024.” P. 8. Prior to this document being released, many municipalities within the Greater Horseshoe were required to implement a minimum 50% intensification target.

References

Altus Group (2025). “Municipal Benchmarking 2024 Study.” Prepared for the Canadian Home Builders’ Association. March 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.chba.ca/assets/pdf/CHBA+Municipal+Benchmarking+Study-3rd+Edition-2024_compressed/ (external link) .

City of Edmonton (2025). “The City Plan.” Office Consolidation June 2025. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.edmonton.ca/sites/default/files/public-files/City_Plan_FINAL.pdf?cb=1760652450 (external link) .

City of Edmonton (2024). "Low Density Residential Lot Absorption and Supply." 2024 Annual Report. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.edmonton.ca/sites/default/files/public-files/2024-Lot-Absorption-Annual-Report.pdf?cb=1757025407 (external link) .

Clayton, Frank (2024). “The Globe & Mail is Correct: Ontario Can Learn About Housing in Alberta But Disregards the Importance of Greenfield Development.” CUR blog. November 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/centre-urban-research-land-development/blog/blogentry94-globe-and-mail-correct-ontario-can-learn-about-housing-from-alberta-but-disregards-greenfield-development/.

Clayton, Frank (2024). “The Housing Affordability Benefits of Commutershed Land Use Planning: A Case Study of the Ottawa and Toronto Metropolitan Areas.” CUR. February 6, 2024. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/centre-urban-research-land-development/pdfs/Toronto_Ottawa_CMA_Comparison_CUR.pdf.

Cummings, Madeleine (2025). “Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board votes to initiate process for winding down operations.” CBC News. Last updated: January 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/edmonton-metropolitan-region-board-votes-to-wind-down-1.7439639 (external link) .

Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board (2021). “Growth Plan Overview.” November 2021. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.emrb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Growth-Plan-Fact-Sheet-2021.pdf (external link) .

Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (2024). “Provincial Planning Statement, 2024.” [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.ontario.ca/files/2024-10/mmah-provincial-planning-statement-en-2024-10-23.pdf (external link) .