High-Level Hide & Seek: Mathematics’ Take on a Classic

You’re out yachting at sea. Bright, sunny day. Engine’s running low on gas. Solution? Check the map, hit the throttle and take the quickest, direct route to shore.

The task is straightforward when the destination is clear and conditions are right. But what if the boat is sinking, you’re lost with no idea where the shoreline is, and your energies are dwindling?

Mathematics has the answer.

In search theory, the goal is to develop algorithms to find hidden objects. These contemporary hide-and-seek’ problems can deepen in complexity by introducing various conditions or case scenarios. The challenge can demand not just a workable algorithm, but the optimal one guaranteeing best performance with greatest efficiency.

Although explored theoretically, search problems have real-world applications — in search-and-rescue operations, property surveillance, evacuation planning, and contexts as diverse as economics, computer science and biology.

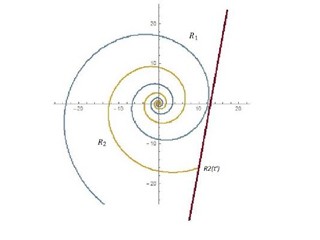

Double spiral trajectories followed by two robots where R1 (robot 1) closely missed the shoreline and R2 (robot 2) found it later.

Searching for a Hidden Shoreline

For her master’s thesis, Sumi Acharjee investigated a problem similar to the one in the outset: finding a shoreline, of which the location is unknown. What’s the most efficient trajectory: a ray, spiral, zigzag, or some other path? Does that change if there are two, three, four or more searchers?

When this two-dimensional search problem was introduced decades ago, mathematicians proposed various algorithms aimed at optimizing their competitive performance. They compared their own algorithms against the time it would otherwise take using a straight, direct route to shore had they known its location. Their results gave, in the language of mathematics, a number of upper bounds to the problem — that is, guarantees that the optimal solution is no more than certain values.

But upper bounds are no guarantee of optimality. To determine that, you also need to know the problem’s lower bounds — in this case, the threshold values (or termination times) that no algorithm can beat. When both upper and lower bounds match, an algorithm with the same performance is the optimal one.

So far, very few and very weak lower bounds had been reported for the shoreline problem — not even accompanied by formal proofs. Without these touchstones of mathematical truth, the reported results could not be relied upon with certainty. Acharjee not only tried to find the proofs, but also wondered if the reported results could be improved.

With supervisor Konstantinos Georgiou and co-authors and fellow students, Somnath Kundu and Akshaya Srinivasan, Acharjee succeeded — producing additional results along the way. Amid the competitive backdrop of theoretical computer science, their research results (external link) were presented and published at the 23rd International Conference on Principles of Distributed Systems in Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Proved, Improved and Optimized Results

“It’s easier to simply propose any workable strategy than to prove that yours is the optimal one,” explains Acharjee. “We initially suspected that the previously reported search times could not be improved in the worst-case scenario, and we set out to prove our conjecture.”

But when Acharjee re-examined the previously reported lower bound for a two-person search. she actually succeeded in finding and proving better lower bounds — setting a new performance measure for algorithms involving a two-person search.

Upper bounds for three-person searches had also existed for decades. But Acharjee is the first to establish lower bounds for this scenario — creating the first available reference point to gauge algorithmic performance in a three-person shoreline search.

For the four-or-more person scenario, Acharjee not only proved new lower bounds, but also matched it to the best upper bounds known so far — thereby reaching the coveted optimization point and closing the books for all time on that particular scenario.

“Adding to the Heritage of Mathematics”

Reminiscing on her results, Acharjee, like other math purists, speaks warmly of the wonderment and philosophical underpinnings of the discipline.

“I still remember the exact moment when we first proved the case for four or more searchers.” Acharjee relates. “Imagine that this variation was a mystery for decades, but we uncovered the optimal result. That was a huge achievement, and an amazing moment.”

Acharjee’s results may yet prove useful in devising strategies for future search operations.

“Mathematics is a global heritage. When we discover new theorems and prove our results, we gain a better understanding of our conceptual world. Our progress makes mathematics richer, and we add to its heritage for others.”

Acharjee’s work was funded by Ryerson University and NSERC.