Reimagining Water Equity

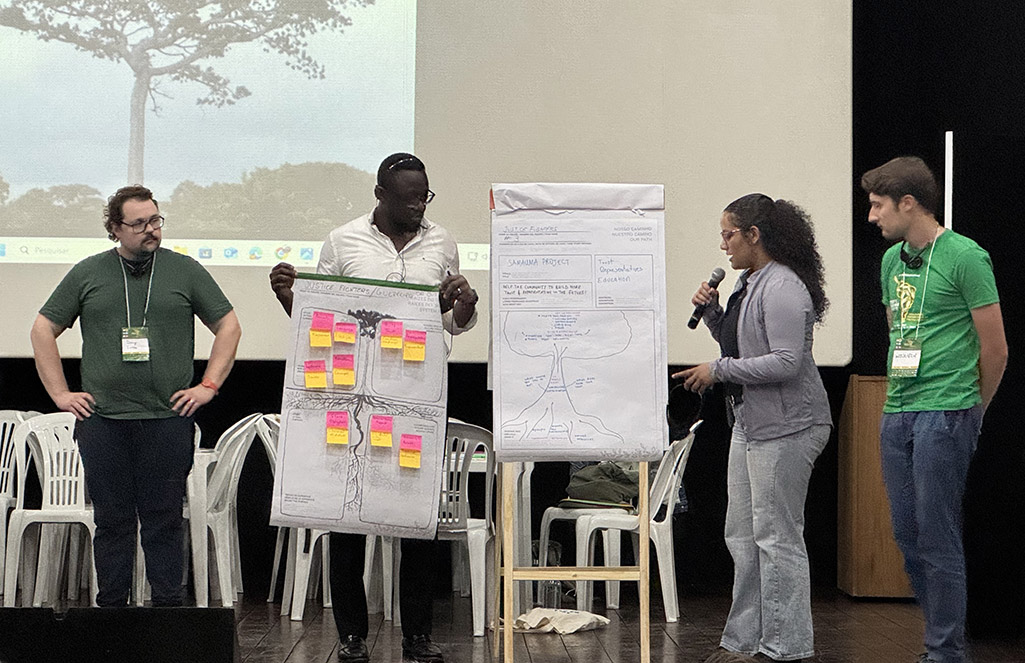

Lincoln Alexander Law's Professor Priscylla Joca (centre) travelled to Brazil this past summer with Rachel Wickham (left) and Kingsley Eze (right) to attend the Participedia School on Democratic Innovations in Latin America.

Professor Priscylla Joca sees law as being in constant movement and responsive to external forces, much like water. So it’s fitting that she’s currently researching water equity and reciprocity, funded by a Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Explore Grant as well as grant funding from Toronto Metropolitan University.

Her research explores how the degradation and pollution of water constitute environmental racism against Indigenous peoples as well as discrimination against other marginalized populations in Canada, such as rural and low-income Canadians. “Because water has no physical boundaries, the river that remains unsafe for Indigenous communities is the same river that nourishes the lands on which non-Indigenous people live.”

In collaboration with Anishinaabe law professor Larissa Speak at Lakehead University, Joca is examining how Anishinaabe laws and worldviews conceptualize water reciprocity. While the concept in international law refers to how citizens of two or more countries can share access to privileges, water reciprocity, in Anishinaabe law, conceptualizes water as a living relative which sustains life and to which humans have sacred responsibilities. If water reciprocity is respected, water can enrich humanity, other living beings, and the ecosystem, Joca explains. “Anishinaabe law provides a powerful counter-teaching to Eurocentric ways of seeing the natural world as a resource to extract - often violently,” she says.

Through this research, Joca explains that she has come to understand “water reciprocity” as being reflected in Anishinaabe water-walking practices. Beginning in 2003, Anishinaabe women, including Josephine Mandamin, have undertaken ceremonial walks to honour and protect nibi (water) where individuals carry water in a copper pail, often taking turns so the water keeps moving. As Joca understands it, this continuous movement echoes the way water itself flows. Some walks follow the shorelines of lakes and rivers, while others carry water along routes connecting different waterways. At a walk’s end, the water may be returned, with ceremonial offerings, as an expression of a sacred responsibility to care for water.

In addition to working with Speak to study the Great Lakes, Joca’s team includes four Lincoln Alexander Law students and one Lakehead Law student. As the SSHRC Explore grant supports research in its infancy, the research team is working to outline a broad understanding of how the tensions and gaps between federal, provincial, and Indigenous jurisdiction affect water equity and reciprocity, which could provide the basis for legal and political solutions.

“We need to make space to reimagine relationships between legal orders so that Indigenous communities can practice water governance along with provincial municipalities and the federal government,” she explains. “This would be beneficial for all of us.” As an example, Joca points to her birth country of Brazil. Although there is a “huge gap” between what the law affirms and how this is enforced, federal law in Brazil encompasses a broader understanding of Indigenous territorial governance that includes not only the right to land but also the protection of water bodies.

For Joca, the research with Speak also exemplifies what feminist political ecology scholars describe as relational approaches to nature – ways of understanding humans, more-than-humans, and water as deeply interconnected rather than separate entities. In a recent publication (external link) with Dr. Catherine Viens, Joca examines how feminist political ecology engages with decolonial thought and Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Central is the Latin American concept of cuerpo-territorio (body-territory): the understanding that Indigenous women's bodies are constitutive of their traditional lands, waters, and territories. Developed by community feminists including Lorena Cabnal (Maya Xinca), Julieta Paredes (Aymara), and Gladys Tzul Tzul (Maya K'iche'), this framework reveals how violence against bodies and violence against lands and waters are interconnected, and express Indigenous ways of knowing and being rooted in reciprocity and care.

Teaching the next generation of environmental lawyers through compassion and humility

In addition to her research, Joca teaches environmental law and provides mentorship to TMU students and visiting scholars from Brazil, including Anderson Santos, a federal judge who researches international justice and human rights (University of Brasilia); and Kethlyn Winter, who is researching Indigenous self-determination (Military Sciences of the Army Command and General Staff School). “My colleagues at the law school are opening up their offices and supporting our visiting scholars, and I’m so appreciative of that,” says Joca. “We’re developing emergent, critical, and unique scholarship at Lincoln Alexander Law and we have so much potential to advance justice across both Global North and Global South contexts.”

As a teacher, Joca aims to train lawyers who recognize the living, evolving nature of law, and can communicate legal justice issues to the wider public. For example, for her Legal Issues in Indigenous Economic Development class, her students produced podcasts where they were tasked with explaining a relevant legal issue in an accessible way. “I was impressed with how the students articulated complex areas of research in ways that different communities in Canada could engage with meaningfully.”

For another class, students visited a park or protected area in Toronto to examine how industrial practices and colonialism have affected the land and how communities use and interact with it - grounding their reflection in environmental law frameworks, Indigenous epistemologies, and environmental and ecological justice.

When Joca talks about her students, she speaks with awe. “When I was a student, I approached law from a positivistic view, and later I learned how to critically understand law and even later, interrogate law from an anticolonial view,” she says. “From the beginning, my students are learning how the law operates even as they are being called to reimagine the entire system…and this is what is shaping them into excellent lawyers.”

Rachel Wickham, who graduated from Lincoln Alexander Law and is currently articling at West Toronto Community Legal Services, worked with Joca as a research assistant earlier this year. Together, they examined how international law often overlooks many of the rights particular to Indigenous women and girls, as well as how the right to exist applies to Indigenous communities in the Amazonas region in Brazil. “She gives so much space for people to be heard, and this ends up really impacting the research in a valuable way. It feels more human and less clinical, and it ends up doing greater justice to and honouring people’s stories,” says Wickham.

Wickham travelled with Joca, as well as Kingsley Eze, currently in his third year at Lincoln Alexander Law, to attend the Participedia School on Democratic Innovations in Latin America, held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil this past summer.

Over the eight-day trip, the students interviewed community leaders, attended workshops and visited a Quilombola settlement, which was formed by escaped enslaved Africans and their descendants in the 16th century. “It was a privilege to learn from these communities,” says Wickham.

Along with program participants, Kingsley Eze and Rachel Wickham present a case study on democracy and access to justice for Indigenous peoples at the Participedia School for Democratic Innovation.

Eze recalls that Joca had written a case study that proposed solutions to food sovereignty and other legal challenges facing Afro-Indigenous peoples. “We saw how much Professor Joca meant to the community in the advancement of their struggle, and how the leaders of the community really welcomed her,” Eze says.

After taking two of Joca’s courses during the fall term, Eze has come to deeply appreciate her innovative pedagogy. For example, every week, the students were tasked with writing a journal entry reflecting on what they learned and how it has impacted them, culminating in a letter to their future selves. “I’m excited to go back five years down the road to see how I have changed and to recommit to the ideals of justice that I learned in class,” he says.

“It almost becomes ingrained to question your positionality when you’re learning from or collaborating with Professor Joca,” says Eze. “It makes you realize how much privilege you bring to a topic or how much you don’t know about a topic, and it makes you move forward with humility and curiosity.”