Level Justice Fellows shine a light on gaps in Toronto’s Mental Health Court

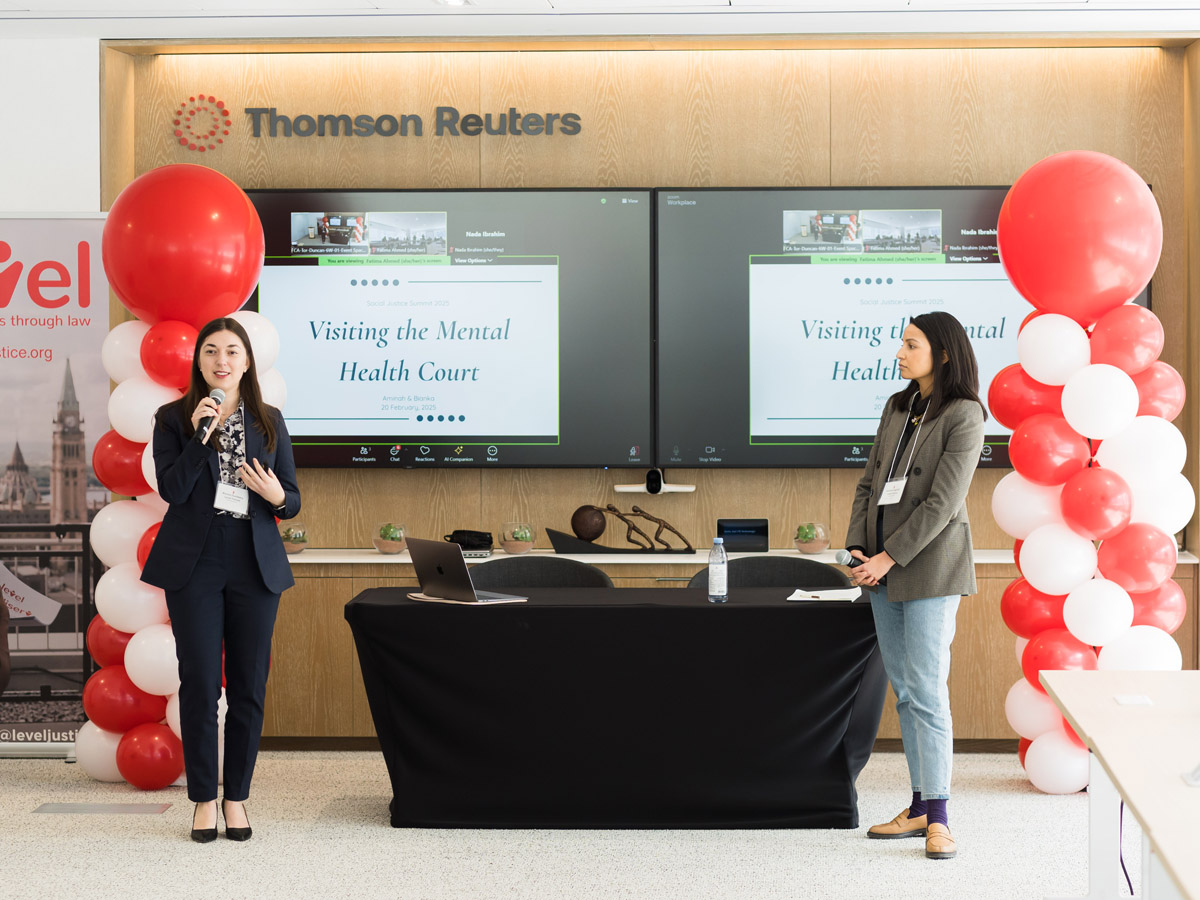

Law students Bianka Dunleavy (left) and Aminah Haghighi presented their research ideas at a Social Justice Summit last February.

Two Lincoln Alexander Law students recently published a comprehensive evaluation of Toronto’s Mental Health Court (TMHC), highlighting barriers to access, including inadequate staffing and narrow eligibility criteria. The TMHC is a specialized diversion court designed to address the intersection of mental health and the criminal justice system by emphasizing treatment and rehabilitation over punishment.

Bianka Dunleavy and Aminah Haghighi researched and wrote the report over the 2024-2025 academic year while serving as Social Justice Fellows at Level Justice (external link) . The two students were among 20 fellows across Canada who received funding, training, and mentorship to pursue a social justice research project. The fellows’ research findings were published (external link) in the Journal of Law Student Scholarship earlier this fall.

When Dunleavy first shared a social media post last year inviting her fellow law students to collaborate on a project, Haghighi jumped at the chance. “I liked the idea of doing academic research on what is happening at the Mental Health Court just down the street from us, an opportunity that we’re afforded as a uniquely urban, downtown law school,” explains Haghighi.

Both students, then in their second year of law school, interviewed mental health court workers and legal experts, as well as people with lived experience with mental health courts and the criminal justice system. In addition to benefitting from mentorship offered by Level Justice staff, Haghighi and Dunleavy attended the Social Justice Summit held in Toronto last February. Fellows were invited to present their projects and received feedback and guidance from other fellows and mentors. “It was really meaningful to meet the other fellows, work through our ideas together, and learn about their research topics,” says Dunleavy.

One of the key challenges identified in Dunleavy and Haghighi’s research was that the TMHC no longer has dedicated judges or Crown lawyers. This means that the judges currently assigned to the court have less time to devote to its cases than before. In addition, they may also lack the same level of familiarity with and understanding of mental health challenges as past judges and Crown counsel. For Dunleavy, “This clearly represents an access to justice issue.”

Another challenge they highlighted is that the eligibility criteria of the TMHC is narrow, as cases involving crimes like dangerous driving or assault generally cannot be heard by the TMHC, regardless of the individual’s mental health challenges. Unlike similar courts in Canada, the TMHC has a limited definition of mental health that fails to take into account that mental health challenges often overlap with addiction and cognitive disability.

In addition to dedicated judges and Crown counsel, and broader eligibility criteria, Dunleavy and Haghighi’s research report calls on increased awareness about the existence of the TMHC option, standardized evaluation criteria for specialized courts, and culturally appropriate treatments.

Dunleavy adds that talking to Nikoleta Carcin, who had previous experience with a drug court and now works as a consultant and researcher, made her realize the important role that specialized courts can play. “Nikoleta changed her own life, but if her lawyer didn’t advocate for her case to be diverted from criminal court, she may not have received the tools and support to do so,” Dunleavy said. “Speaking to her made me appreciate the profound role lawyers can play in people’s lives.”

Tasha Stansbury, Environmental and Social Justice Program Manager at Level Justice, described the importance of Dunleavy and Haghighi’s interviews with judges, lawyers, support workers, and individuals with lived experience, as well as attendance at conferences featuring experts on therapeutic justice. “Their final work reflects the well-roundedness of their research; it includes not only legal and systemic considerations in their recommendations, but also the interpersonal human aspects of participation in diversion programs,” she says. “The purpose of Level Justice’s fellowship program is to support students with a passion for social justice. In equal measure, we are supported and bolstered by our fellows.”

Haghighi shared how the experience had a profound impact on her. “I came into law school thinking that I would want to graduate and practice right away. This opportunity made me realize that I love doing research, so now I’m thinking about the possibility of grad school,” she says.

The ongoing collaboration with Level Justice reflects Lincoln Alexander Law’s broader commitment to experiential education, equity, and community-engaged learning. The law school recently engaged the organization to deliver Cultural Humility and Empathy Training (external link) to first-year law students as part of the JUR 400: Law and Legal Methods intensive course held at the start of the fall term.

Desneige Frandsen, a graduate of Lincoln Alexander Law’s inaugural class, currently serves as the Indigenous Justice Program Manager at Level Justice. Together, she and Shelan Markus, Executive Director at Level Justice, have provided cultural humility and empathy training to several organizations including McCarthy Tétrault, LexisNexis, and the John Humphrey Centre for Peace and Human Rights, but Lincoln Alexander Law is the first law school to incorporate the training into a mandatory law course.

“The cultural humility and empathy training helps us to fulfill Calls to Action #27 and #28 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which relate to cultural competency for law students and the legal profession, and ensuring training on Indigenous history, treaties, and Indigenous law,” Frandsen explains. She adds that cultural humility is not an end goal; instead, it means a commitment to continually confront biases, misconceptions, and gaps in one’s understanding. “The learning process is never over.”

This work is supported by government entities, law firms, other non-profit organizations, charitable foundations, law societies, and individual donors. “They play a huge role in making sure that our programs continue to be as impactful as they can be,” says Frandsen, who will provide similar training to fellow alumni at an upcoming professional development and networking event.

According to Shelan Markus, Level Justice and Lincoln Alexander Law share “a commitment to building equitable justice systems and challenging the status quo.” In addition to hiring Lincoln Alexander Law alumni, recruiting research fellows from the school, and offering cultural humility training, Level Justice also invites Lincoln Alexander Law students to volunteer in youth justice education programs. “This work reflects our commitment to removing barriers to justice, disrupting prejudice, and advancing human rights,” Markus says.