Complex Systems Series: Spotlight on Eric De Giuli

Complex Systems professor, Eric De Giuli

Like many budding physics students, a younger Eric De Giuli had also once entertained dreams of becoming the next Einstein. But realization soon dawned: illustrious forebears had already demystified the fundamental laws of physics.

Now a professor at Ryerson University’s Department of Physics, De Giuli has since surmounted that intellectual wall, and is helping next-generation physicists do the same. His message: expand traditional mindsets, and apply the tools of physics to fresh areas that, until now, have existed outside its purview.

De Giuli has been a key figure in debuting the new complex systems graduate field at Ryerson. In a recent interview, he talked of his research on the statistical physics of disordered systems, the outlook for complex systems, and what students can expect conducting research in his lab.

What exactly is the ‘wall’ that physics students often hit?

Physics has always been exciting because it makes sense of the world, supplying engineers with fundamental equations that can be used to address societal needs. But in a sense, particle physics has become a victim of its own success.

We already have a nearly complete model of the fundamental building blocks of nature: the Standard Model, whose predictions have been verified to astounding accuracy. So, what remains unknown, such as the interiors of black holes, are often way out of the range of human experience. It can be disheartening for students looking for a direction to head in.

So, you feel physics needs to move in a new direction — where and how?

It’s not about leaving physics, but adopting a new mindset. Once we expand our understanding of what physics is, there’s so much more to discover — such as how the brain works or neural networks in machine learning.

What’s exciting now are emergent phenomena that appear in complex systems with a huge number of interacting parts. We see this happen all the time in physics, but it’s also relevant in wider domains. So, if we start using our powerful quantitative tools to make sense of it all, those new problems can be seen as physics problems.

Complex systems is a relatively new field. What’s the outlook?

Ryerson is now one of the only universities in Canada to offer formal training in complex systems. We’re creating everything from scratch, with new courses and a variety of research opportunities. So, our graduate students will have an early opportunity in this field.

The pandemic has plainly illustrated how interconnected our world is. That’s complexity: it’s not enough to understand individual parts, because they can coordinate to create large scale, unpredictable behaviours. A critic might see this as a futile desire to understand society down to the smallest detail, but that’s not quite right. We need to let go of the idea that we can predict everything exactly.

Part of complex systems thinking is taking an ‘ensemble’ perspective, to consider a whole spectrum of possibilities, rather than insisting on one single outcome. Once you do that, it totally changes your view, and we can then start designing better systems that are robust enough to handle fluctuations and instability.

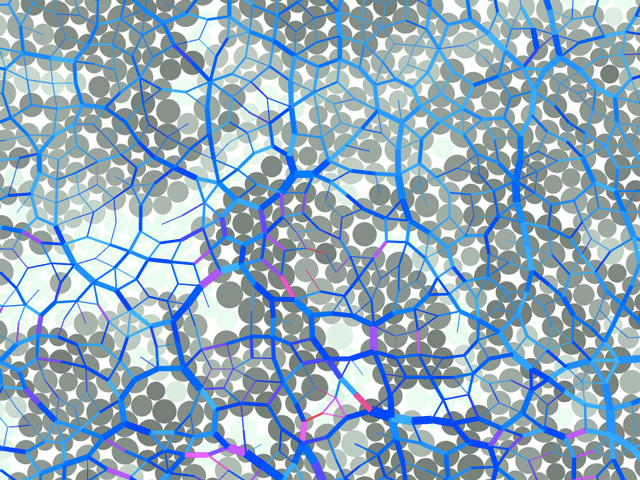

Flow of granular material, illustrating emergent patterns generated from interacting elements within complex systems.

Specifically, you’ve used statistical mechanics to study complexity in glass, chemical systems, and even language?

Yes, I look at systems that are not in thermal equilibrium, and how their metastable states at the microscopic level affect their macroscopic, large-scale behaviours. There’s a whole new world of physics out of equilibrium!

For example, most liquids will become a glass if rapidly cooled. This is a transition from a fluid to a solid, but unlike a crystal, the glass is disordered at the microscopic level, with many possible molecular configurations, all out of equilibrium. Part of my research is on structures near these rigidity transitions. Moreover, this type of phase transition is a prototype for many real-world transitions, say in ecosystems, economies, and yes, even languages, where there are no special crystalline arrangements.

What exactly was that connection you made between physics and language learning in kids?

By using analogies of things we’ve already seen in statistical physics, we can map this very complex problem and understand it better. When children learn language, they also go through a phase transition — from a state where they’re babbling random words to one where they’re using syntax to form comprehensible sentences. How do they make this largely automatic transition?

Essentially, as a child is continuously updating their grammar by imitating their caregivers’ speech, the likelihood of utterances varies. At some point, the sheer number of ways they can babble (which is entropy) becomes less important than the bias towards producing 'correct' utterances (which is energy). This competition between energy and entropy is well-known in physics. I expect that each phase of learning follows this pattern, although much remains to be understood.

This project is part of a larger theme of systems in which rich structure emerges spontaneously. Obviously this is central to biology, whose beginning is one of the great scientific mysteries of our time: how did metabolism spontaneously emerge in a chemical reaction network? To answer this, I’m now making a cautious foray into the wild world of complex biological systems.

What’s the ideal student profile for your lab?

There’s a lot of math, simulation coding, and data analysis. So, candidates should have a background in physics, high proficiency in math, basic coding skills — and an interest in researching emergent phenomena.

Overall, for students who feel they’ve hit a wall in fundamental physics, I want to show them that physics does continue — that its horizons can expand into attacking new, more complex problems beyond what’s traditionally recognized as physics.