TMU graduate researcher develops new methods to identify and assess toxic plastic additives in the environment

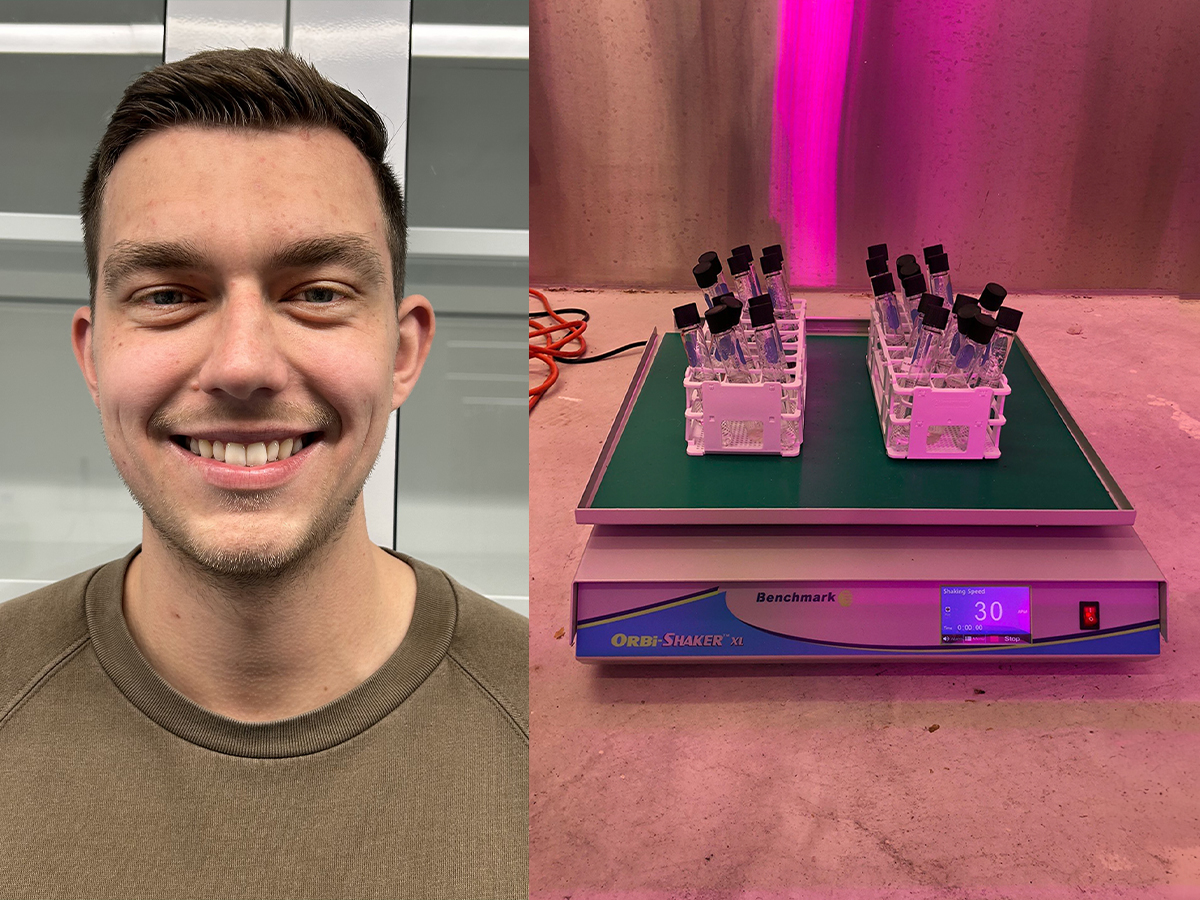

Eric Fries tested how UV light affects the way different plastics leach into water as part of his research in the Emerging Contaminants Lab. Photo: Supplied by Eric Fries

A Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) researcher has developed two first-of-their-kind methods to analyze harmful chemicals commonly used in plastics and assess how they make their way into our environment and waterways.

Eric Fries, an environmental applied science and management PhD student, designed two methods to examine a group of persistent, mobile and toxic (PMT) chemical additives. PMTs, such as flame retardants and waterproof coatings, are used in numerous plastic products, from toy balls to medical face masks. They do not break down easily, can pass through water treatment processes and are known to be toxic. Some PMTs are carcinogenic, while others can disrupt endocrine and reproductive systems.

“We’ve only really become aware of these PMTs in the last 10 years or so,” said Fries. “There’s not a lot of research on how they enter the environment.”

To learn how PMTs enter the environment, Fries first needed to develop a method to identify the individual PMTs in a water sample. Using specialized equipment, he tested different solvents to see which would result in the best separation of molecules. Once the molecules were separated, he was able to compare them to a database of known chemicals to pinpoint which individual PMTs were present in the sample.

Fries then created an optimized protocol to calculate and assess the amount of each chemical that leached into the water sample. He also tested the chemicals under various conditions, such as light levels, water turbulence and in both freshwater and saltwater, to see how environmental conditions affected their levels. As a result of his research, Fries found that all PMTs do not act the same when leaching from plastic into water, and they must be studied individually.

These two new methods developed by Fries lay the foundation for continued research and can be used to monitor PMTs in the environment, including waterways. Knowing the concentration levels of different environmentally present PMTs will allow researchers to better assess their risks to humans and other organisms.

“The big issue with these chemicals is that they are virtually unregulated in Canada and the rest of the world. They’re free to be used at any level,” said Fries.

Fries continues his research in TMU’s Emerging Contaminants Lab with supervising professor Roxana Sühring, whose expertise is in environmental analytical chemistry. The next step in the research is to test Fries’ novel methods on more plastics. He is also working on additional research to compare the levels of PMTs present in used plastic products collected in the environment with PMTs levels present in their new, store-bought counterparts. Another area of investigation includes examining the differences in PMT levels in recycled and non-recycled plastics.

Read "The unusual suspects: Screening for persistent, mobile, and toxic plastic additives in plastic leachates" (external link, opens in new window) published in Environmental Pollution.

Learn more about the Emerging Contaminants Lab.