What’s Underneath the Surface: Plastic Pollution and the Hidden Chemical Threat

Maybe you’re reading this at the office with your morning coffee, delaying the start of the workday. Maybe you’re waiting for the subway or bus, which has been delayed for another 10 minutes (classic). Maybe you’re reading this in bed, in hopes that it will put you to sleep. Either way, have a quick look around you, and try to spot some items that you think are made of plastic…

That was probably pretty quick, right? Heck, the phone or computer you’re reading this on is chock-full of them. It’s undeniable that we live in a plastic world. Ever since the advent of plastics at the start of the 1900s, they have gradually taken over our society, replacing products that were traditionally made from glass, metal, wood, or other simple materials. It’s hard to deny the usefulness and efficiency of plastics; they are lightweight, easy to manufacture and scale-up, and can be produced at a fraction of the cost of those traditional materials. Most importantly, they have undeniably changed the course of technological advancement and engineering. From the pipes we use to transport clean water to our homes, to the medical devices that have revolutionized healthcare, plastic has become inextricable from our daily lives. What we didn’t think of, though, is what happens to all this plastic when we are done using it?

Unlike those traditional materials, plastic doesn’t break down easily. Where wood can take a few years to decompose under the right conditions, plastics can take upwards of 500 years. Where glass, for example, is easily recycled and made anew, plastic recycling is very finicky, with global recycling rates (external link) at only 9% (in Canada, this figure is 6%). As such, roughly 350 million tonnes of plastic waste enter our landfills every year, with a large portion of this waste entering the environment. Our oceans, lakes, rivers, and seas see tens of millions of tonnes of plastic waste annually, often disrupting key ecosystems and food chains. Over time, these plastics in the environment do break down into (or start life as) microplastics and nanoplastics, terms that have become more and more common in our cultural zeitgeist. Describing plastic pieces that are a million or a billion times smaller than a metre, micro- and nanoplastics are a growing issue, being found in countless species of fish, birds, and increasingly, humans. These tiny plastics are a problem; they are extremely hard to remove from the environment and can disrupt a bunch of bodily functions in many organisms. What we often don’t consider when talking about plastic pollution, though, are the chemicals associated with these products.

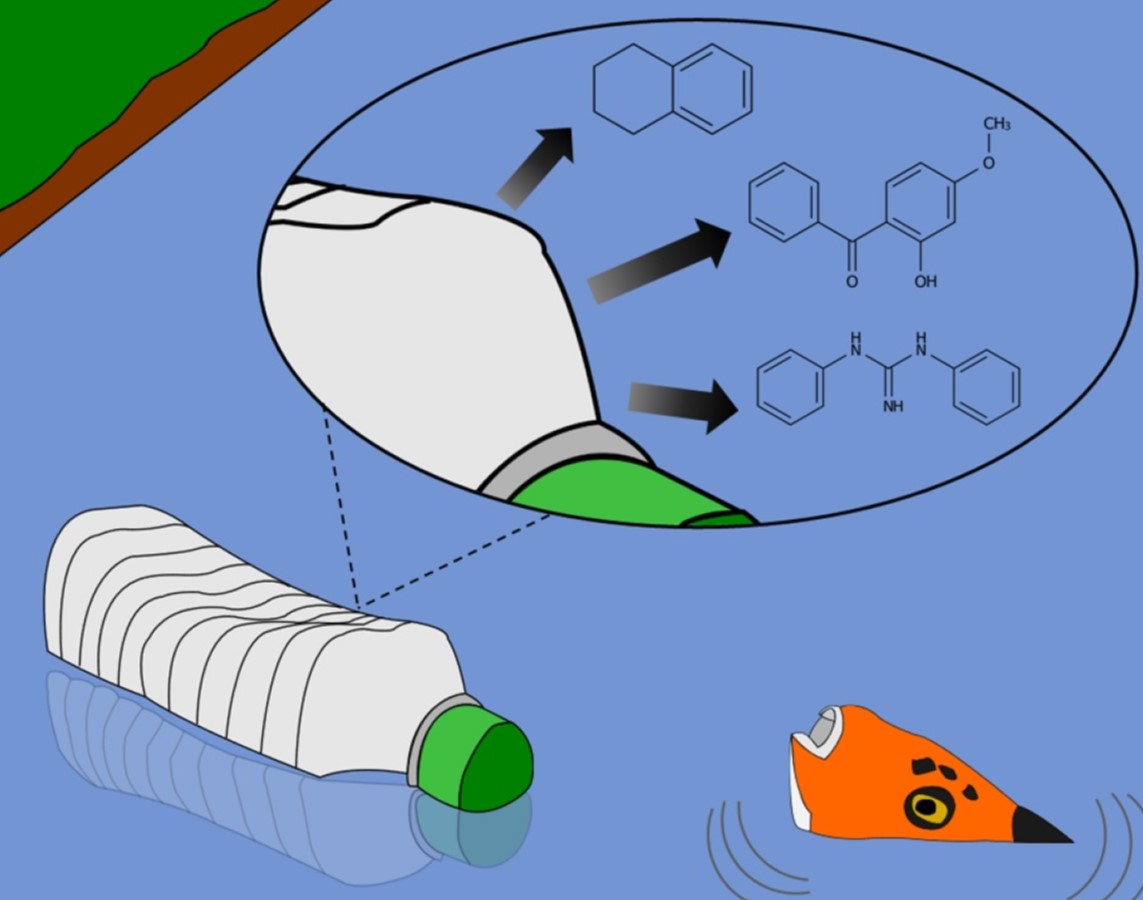

Plastics come in countless shapes, colours, and sizes, because of the chemicals that are added to them, fittingly called plastic additives. These additives have a growing number of applications, from flame retardants that make a product ‘fire-proof’, to plasticizers that make a product more flexible, to colourants that cover every shade of the rainbow. All of these plastic additives have an application, whether necessary or not, and are worked into the plastic during manufacturing. While important for a variety of applications and functions, many plastic additives have shown toxic properties, with several additives having been linked to cancers, endocrine and reproductive disorders, and many, many more. What’s important to note is that for the most part, plastic additives are not chemically bonded to the plastic material, they are instead physically worked in. This means these chemicals are not strongly bound to the plastic, so when a product ends up in the environment, the additives can leach out over time. On a small scale, this isn’t very significant; the amount of additives in a given product can be on the scale of a millionth or a billionth of a gram. But, consider the millions of tonnes of plastic waste that end up in our water bodies every year, and the thousands of known additive chemicals in use – this adds up to a massive and complex chemical contamination issue. You can think of every single plastic bottle, bag, straw, or microplastic, like a little tea bag of (typically toxic) chemicals, slowly steeping away in that water body. Moreover, many of these additives are hard to remove from water using standard wastewater or drinking water treatment processes, meaning they can recirculate in the environment and potentially concentrate over time. This is where my research comes in.

Over time, plastics leach additive chemicals into water bodies, acting as a major source of contamination.

In my work with Dr. Roxana Suehring, I focus on a group of plastic additives that are persistent, mobile, and toxic (PMT). Persistent means that they don’t break down easily in the environment, often surviving months or even years before breaking down. Mobile means that they are hard to remove from water and can often travel great distances in a variety of environments without being removed. Finally, toxic is rather self-explanatory, with these chemicals being associated with cancers, endocrine disorders, and many other health conditions. Together, these properties make for a dangerous set of emerging contaminants, one that our current water treatment facilities are unable to deal with. Since we have only become aware of PMTs in the last 10-15 years, there is plenty of work to be done in the field. My work in the Emerging Contaminants Lab at TMU homes in on these PMTs and their use in plastic products. In 2022, we published the first study of PMT plastic additives in Canada (external link) , identifying the PMTs that are used in the country, and simulating their behaviour in a typical wastewater treatment plant. Unsurprisingly, of the 124 PMTs that we identified, over half showed that they would have very low removal from wastewater, ending right back up in the environment. A year later, we published two first-of-their-kind methods (external link) to study PMTs: one to study how PMTs leach out of plastics, and one to measure PMT plastic additives in water. We continue to use both methods frequently, applying them to a growing library of plastic products with the hopes of being able to better identify sources of PMT contamination in the environment.

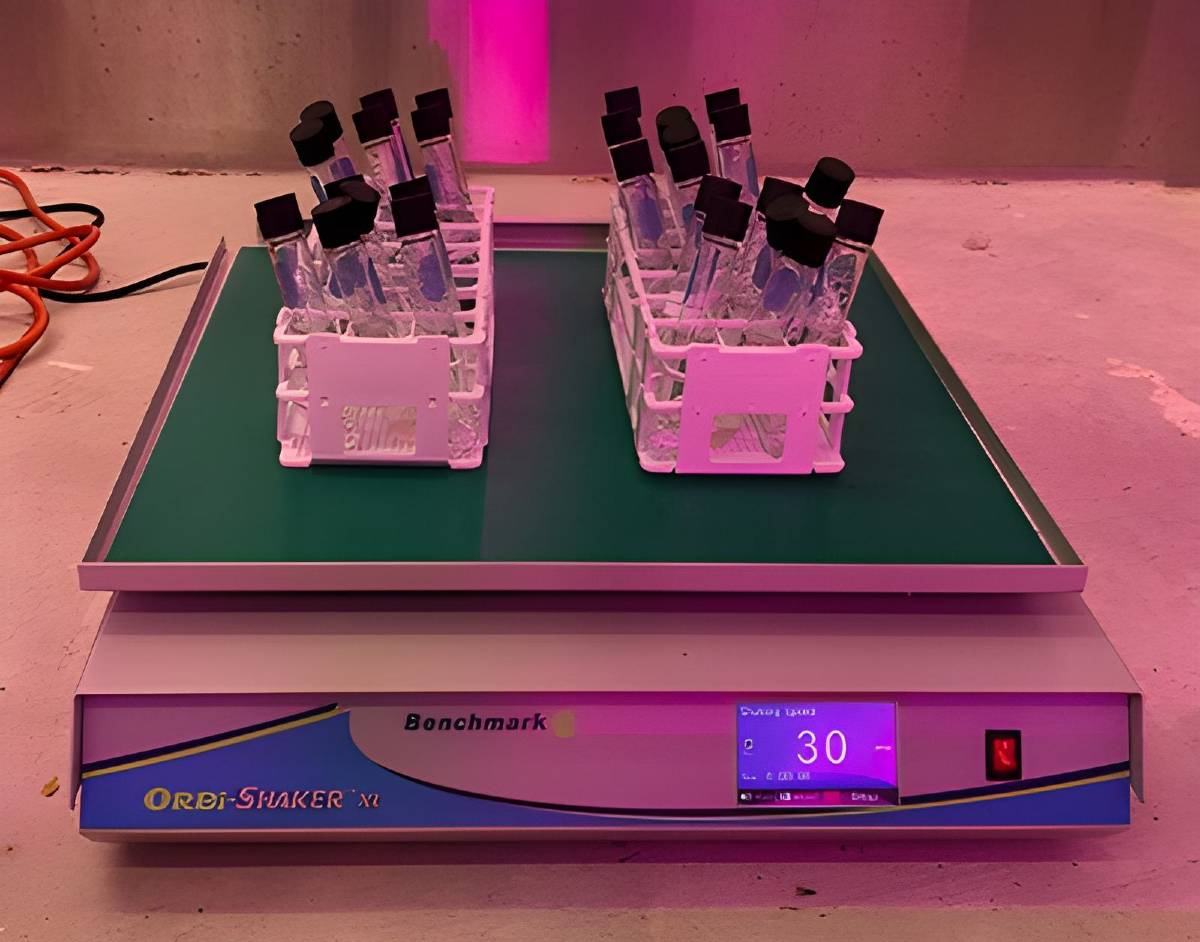

The set up of a PMT leaching experiment. Test tubes containing plastics and lake water sit on a shaker, simulating water turbulence, and under a UV light, simulating a day-night cycle, all to best simulate real environmental conditions.

Moving forward, I continue to work on PMT plastic additives as part of my PhD research. I am now applying these methods to nearly 70 plastic products, from children’s toys and plastic bottles, to construction materials and cigarettes. By looking at where these products came from, what polymers they are made of, and their lifecycle in the environment, we hope to better understand which PMTs are used in what products, which products may be a greater threat for PMTs, and where these PMTs are ultimately coming from. I am also looking to build upon our current methods, making them more accurate, confident, and applicable to a larger range of PMT compounds. Through improving these aspects of the method, we can continue these experiments being more confident in the exact identities and quantities of the PMTs in these plastics, providing more actionable data for regulators or monitoring bodies. Moreover, I am looking to measure PMTs in the Canadian Arctic, an area which often incurs pollution and contamination issues they had no hand in creating. Through investigating PMTs in these regions, we hope to better understand how PMTs travel to the Arctic, which PMTs may be the greatest threat in these regions, and how they may be impacting key water or food resources. All these works aim to improve our understanding of PMTs, plastic pollution, and how we can deal with these chemical threats.

The new plastic world can be a daunting one the deeper you dig, but it is one that is not without hope. It is virtually impossible for us to remove all the plastics from our lives (especially on a student’s budget), but small changes do make a difference. Switching from plastic water bottles to a reusable, metal bottle. Remembering to pack your reusable shopping bags before that trip to the grocery store. Donating your old clothes, toys, or furniture to give them a new life. All these little changes accumulate, keeping plastics out of our landfills and waters, and just as importantly, keeping these chemicals out of the environment. The battle against plastic pollution is one that will take time and understanding, but it is a battle that we can win when we look at what’s underneath the surface.

Eric Fries is a PhD student in the Environmental Applied Science and Management program at TMU. His research, supervised by Dr. Roxana Suehring, specializes in the study of emerging contaminants associated with plastic pollution, developing new analytical and preparative methods to do so. Through this work, Eric has collaborated on projects with Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Northern Contaminants Program, international partners in the United Kingdom, Germany, and more.

Questions about the article? Contact Eric Fries directly at: eric.fries@torontomu.ca