Using Labour Market Information to Make Skills Development More Inclusive

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, paired with ongoing technological advancements, has caused a “ (PDF file) double disruption (external link) ” for workers and job seekers and necessitated a change in how we work and in the skills we need to thrive in this shifting labour market. Globally, we are seeing that (PDF file) digital skills and skills associated with innovation and entrepreneurship are increasingly in demand. These include skills such as resilience, stress tolerance, flexibility, leadership, and technology use. Similar trends are observed here at home: social-emotional skills and basic or mid-level digital skills are frequently called for among Canadian employers. Indeed, Canada’s Skills for Success Framework (external link) identifies several (PDF file) social-emotional skills (external link) (i.e., problem solving, communication, collaboration, adaptability, creativity, and innovation) and digital skills as essential for navigating today’s rapidly changing world.

Though seemingly innocuous, the demand for social-emotional and digital skills has significant implications for equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in the labour market and the workplace. Evidence suggests that members of equity-deserving groups, such as Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities, women, racialized persons and newcomers, often face discrimination in the assessment of their resumes, credentials, and skills (external link) , particularly their social-emotional skills. Yet, it is wrong to presume there is a trade-off between diversity and qualification; on the contrary, addressing biases and creating more (PDF file) inclusive workplaces can only increase the pipeline of talented candidates. Part of the solution in addressing these inequities involves better assessment of and training in social-emotional skills and better access to inclusive skills development services.

This research summary is part of the Labour Market Insights series funded by the Future Skills Centre and led by the Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University. This article weaves together two themes—skills development and EDI—to explore what the skills-development ecosystem can do to advance EDI in its work. First, we provide recent labour market information on the most in-demand skills in Canada to provide guidance to employment service providers on what skills their clients need to develop as the economy continues to grapple with the pandemic. We then discuss how to make the assessment of skills and the access to skills-training services more equitable and inclusive. From this, it will be seen that truly equitable skills development will require shifts from multiple actors in the skills-training ecosystem.

Top skills by occupational category and skill level

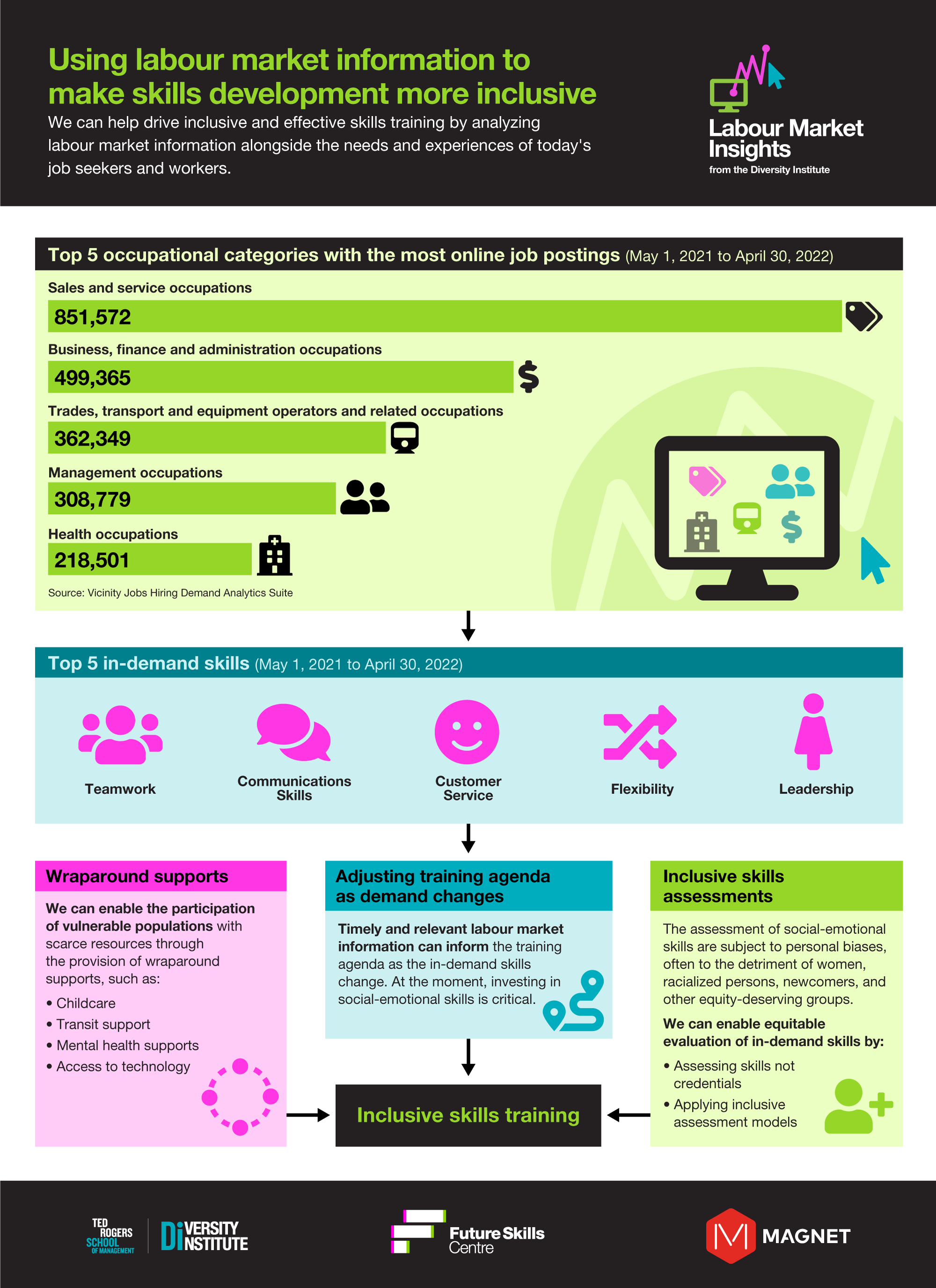

To identify job posting trends and in-demand skills, we use data from the Vicinity Jobs Hiring Demand Analytics Suite to examine job postings during the 12-month period between May 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022 (the most recent data available at the time of this analysis). A unique feature of the Vicinity Jobs database, which collates data about online job postings across Canada, is its ability to extract skills information from job postings and categorize jobs according to occupational type. Between May 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022, there were over 3.2 million online job postings. The occupational categories (as defined by the National Occupational Classification (external link) [NOC] system) with the most job postings during this time period were sales and service (26.5%); business, finance, and administration (15.6%); and trades, transport, and equipment operators and related occupations (11.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1

Number of online job postings by broad category (one-digit NOC code) between May 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022

Broad Occupational Category |

# |

% |

|---|---|---|

1. Sales and service occupations

|

851,572 |

26.5% |

2. Business, finance, and administration occupations

|

499,365 |

15.6% |

3. Trades, transport, and equipment operators and related occupations

|

362,349 |

11.3% |

4. Management occupations

|

308,779 |

9.6% |

5. Health occupations

|

218,501 |

6.8% |

6. Occupations in education, law, and social, community, and government services

|

177,420 |

5.5% |

7. Natural and applied sciences and related occupations

|

141,701 |

4.4% |

8. Occupations in manufacturing and utilities

|

80,515 |

2.5% |

9. Occupations in art, culture, recreation, and sport

|

33,809 |

1.1% |

10. Natural resources, agriculture, and related production occupations

|

27,998 |

0.9% |

Job postings not assigned to a NOC |

506,074 |

15.8% |

Total |

3,208,083 |

100.0% |

To better understand the skills that job seekers need for different career paths, we identify the top skills by broad occupational category and “skill level,” as defined by the NOC (external link) (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5). The NOC skill level refers to the level of education or training typically required for certain jobs (e.g., university education, college education, apprenticeship, occupation-specific training, etc.). To avoid confusion, we refer to the NOC skill level as “education/training requirements.” Some broad occupational categories only include jobs that require university-level or college-level credentials, while others have jobs where university-level training is not required, so some of the occupational categories are not listed in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Table 2

Top 10 skills for occupations requiring a university education (NOC skill level A)

Rank |

Management Occupations |

Business, Finance, and Administration Occupations |

Natural and Applied Sciences and Related Occupations |

Health Occupations |

Education, Law, and Social, Community, and Government Services |

Occupations in Art, Culture, Recreation, and Sport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Leadership |

Communication |

Teamwork |

Communication |

Teaching and training |

Writing |

2 |

Communication |

Teamwork |

Communication |

Leadership |

Communication |

Teamwork |

3 |

Teamwork |

Microsoft Excel |

Leadership |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

Communication |

4 |

Customer service |

Planning |

SQL (structured query language) |

Planning |

Leadership |

English language |

5 |

Planning |

Accounting |

Agile software development |

Problem solving |

Interpersonal |

Flexibility |

6 |

Flexibility |

Leadership |

Planning |

Interpersonal |

Planning |

Leadership |

7 |

Organizational |

Customer service |

Cloud computing |

Critical thinking |

English language |

Organizational |

8 |

Fast-paced setting |

Attention to detail |

Project management |

Organizational |

Flexibility |

Attention to detail |

9 |

Interpersonal |

Interpersonal |

Problem solving |

Flexibility |

Organizational |

Bilingual |

10 |

Budgeting |

Microsoft Office |

Java |

Decision-making |

French language |

Time management |

Note: Certain broad occupational categories do not have jobs at certain skill levels. As a result, this table does not include all occupational categories.

Table 3

Top skills for occupations requiring college or vocational education or apprenticeship training (NOC skill level B)

Rank |

Business, Finance, and Administration Occupations |

Natural and Applied Sciences and Related Occupations |

Health Occupations |

Occupations in Education, Law, and Social, Community, and Government Services |

Occupations in Art, Culture, Recreation, and Sport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Communication |

Teamwork |

Communication |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

2 |

Teamwork |

Communication |

Teamwork |

Communication |

Communication |

3 |

Microsoft Excel |

Attention to detail |

Interpersonal |

First aid |

Flexibility |

4 |

Organizational |

English language |

Organizational |

Teaching and training |

Customer service |

5 |

Microsoft Office |

Customer service |

Decision-making |

Flexibility |

Teaching and training |

6 |

Attention to detail |

Organizational |

Problem solving |

Interpersonal |

Leadership |

7 |

Microsoft Word |

Interpersonal |

CPR |

English language |

First aid |

8 |

Customer service |

Microsoft Office |

Leadership |

CPR |

Interpersonal |

9 |

Interpersonal |

Troubleshooting |

Flexibility |

Planning |

English language |

10 |

Fast-paced setting |

Bilingual |

Customer service |

Organizational |

Organizational |

Table 3, continued

Rank |

Sales and Service Occupations |

Trades, Transport, and Equipment Operators and Related Occupations |

Natural Resources, Agriculture, and Related Production Occupations |

Occupations in Manufacturing and Utilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

2 |

Customer service |

Communication |

Attention to detail |

Communication |

3 |

Fast-paced setting |

English language |

English language |

Attention to detail |

4 |

Communication |

Attention to detail |

Organizational |

Leadership |

5 |

Flexibility |

Customer service |

Communication |

English language |

6 |

English Language |

Fast-paced setting |

Fast-paced setting |

Interpersonal |

7 |

Organizational |

Troubleshooting |

Work under pressure |

Troubleshooting |

8 |

Attention to detail |

Flexibility |

Leadership |

Flexibility |

9 |

Work under pressure |

Interpersonal |

Customer service |

Occupational health and safety |

10 |

Interpersonal |

Leadership |

Flexibility |

Fast-paced setting |

Note: Certain broad occupational categories do not have jobs at certain skill levels. As a result, this table does not include all occupational categories.

Table 4

Top skills for occupations requiring secondary school and/or occupation-specific training (NOC skill level C)

Rank |

Business, Finance, and Administration Occupations |

Health Occupations |

Occupations in Education, Law, and Social, Community, and Government Services |

Sales and Service Occupations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Communication |

Communication |

Communication |

Customer service |

2 |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

Flexibility |

Teamwork |

3 |

Customer service |

Organizational |

Organizational |

Communication |

4 |

Attention to detail |

Interpersonal |

Teamwork |

Flexibility |

5 |

Organizational |

Customer service |

Interpersonal |

Sales |

6 |

Microsoft Excel |

English language |

First aid |

Fast-paced setting |

7 |

Accounting |

Decision-making |

Customer service |

Attention to detail |

8 |

Microsoft Office |

CPR |

English llanguage |

Leadership |

9 |

Microsoft Word |

Flexibility |

CPR |

Interpersonal |

10 |

English language |

Attention to detail |

Self-starter/ self-motivated |

Organizational |

Table 4, continued

Rank |

Trades, Transport, and Equipment Operators and Related Occupations |

Natural Resources, Agriculture, and Related Production Occupations |

Occupations in Manufacturing and Utilities |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Teamwork |

English language |

Teamwork |

2 |

Customer service |

Teamwork |

Attention to detail |

3 |

Communication |

Fast-paced setting |

English Language |

4 |

Attention to detail |

Attention to detail |

Communication |

5 |

Flexibility |

French language |

Fast-paced setting |

6 |

Forklifts |

Bilingual |

French language |

7 |

English language |

Flexibility |

Organizational |

8 |

Fast-paced setting |

Work under pressure |

Bilingual |

9 |

Organizational |

Organizational |

Leadership |

10 |

Time management |

Interpersonal |

Flexibility |

Note: Certain broad occupational categories do not have jobs at certain skill levels. As a result, this table does not include all occupational categories.

Table 5

Top skills for occupations requiring on-the-job training or no formal education (NOC Skill level D)

Rank |

Sales and Service Occupations |

Trades, Transport, and Equipment Operators and Related Occupations |

Natural Resources, Agriculture, and Related Production Occupations |

Occupations in Manufacturing and Utilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Customer service |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

Teamwork |

2 |

Teamwork |

English language |

Attention to detail |

English language |

3 |

Communication |

Fast-paced setting |

Fast-paced setting |

Attention to detail |

4 |

Flexibility |

Flexibility |

English language |

Fast-paced setting |

5 |

Fast-paced setting |

Communication |

Flexibility |

French language |

6 |

Attention to detail |

Customer service |

Organizational |

Bilingual |

7 |

English language |

Scaffolding |

Customer service |

Communication |

8 |

Organizational |

Interpersonal |

Interpersonal |

Flexibility |

9 |

Occupational health and safety |

Attention to detail |

French language |

Leadership |

10 |

Interpersonal |

French language |

Bilingual |

Interpersonal |

It is striking that the top ten skills sought by employers in each occupational category are largely social-emotional skills (external link) , even when taking into account education/training requirements (see Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5). Teamwork was among the top skills in demand in every broad occupational category and at every level of education/training requirements. Other skills that were frequently called for were communication skills, flexibility, organizational skills, and interpersonal skills. A core set of social-emotional skills emerges clearly as a useful foundation for career growth or transition in any occupational category.

Certain skills may facilitate a pivot between occupational categories. Among jobs that require a university-level education, leadership and planning skills were highly sought after across most broad categories. For jobs requiring on-the-job training or no formal education, the ability to work in a fast-paced setting, attention to detail, and English language were the top skills across all occupational categories. Skills training providers can help job seekers be resilient in a changing economy by offering programs that help develop a core set of transferable skills that are useful across multiple fields and at various stages of a career journey.

While these data show top skills across job categories and at various steps of the career ladder, it does not provide information about the importance of each skill to successful job performance. Indeed, other technical or specialized skills and knowledge of certain tools are certainly relevant and important. As (PDF file) career pivots and job changes become more commonplace over the course of a working life, the prevalence of (PDF file) social-emotional skills across occupational categories (external link) suggests there is value in developing these as a foundational set of skills.

A few caveats are important to note in this analysis. Nearly 16% of job postings could not be assigned to a NOC category (Table 1). Additionally, not all postings had sufficient information about education/training requirements or the skills needed to perform the job, resulting in their exclusion from the analysis (6% to 30% of postings were excluded in each occupational category). To the extent that these exclusions were more likely to occur in certain occupational categories, this may over- or under-represent certain occupations in this analysis. Moreover, 2021 was an unusual year (external link) due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; some sectors were negatively impacted, while others experienced a hiring boom.

Inclusive skills assessments

The demand for social-emotional skills in the past year’s online job postings, including in occupational categories that are traditionally associated with technical or hard skills, supports the argument that (PDF file) social-emotional skills are some of the most essential skills. Demand for these skills, however, needs to be placed in the context of ongoing skills and labour shortages in the Canadian economy. At the same time, the parts of the labour force that are growing, such as Indigenous Peoples, immigrants, or racialized persons, typically experience under-employment.

Canada can look to equity-deserving groups as part of the solution to the country’s skills shortages. However, barriers at the societal, organizational, and individual levels hinder the full participation of members of equity-deserving groups in the Canadian labour force (external link) . At the societal and organizational level, educational credentials have traditionally served as stand-ins for the assessment of individual social-emotional skills, meaning that those who have the means to acquire credentials are more favoured in the job market. Thus, the practice of seeking credentials rather than skills creates a major hurdle in the hiring and promotion process.

Additionally, social-emotional skills, or so-called soft skills, have been shown to be more impacted by personal biases (external link) and prejudices than hard skills. (PDF file) Women and racialized groups (external link) are deemed less likely to possess certain soft skills, or are rated unfavourably on the skills they do possess. For example, women tend to be rated less favourably (external link) in social-emotional skills that are stereotypically seen as “masculine,” such as leadership, which leads to wage gaps and occupational segregation. Racialized Canadians are more likely than non-racialized Canadians to report receiving comments about their communication skills, feeling out of place at work, and experiencing (PDF file) stalling of their career prospects (external link) . Similarly, immigrants, many of whom are racialized, are perceived to possess fewer soft skills than native-born Canadians. This perception is related both to biases about language proficiency and the devaluation of international experience. Without a clear framework to guide the assessment of skills, biases and prejudices can lead to widening inequalities in the labour market.

A focus on improving the assessment of social-emotional skills is critical because addressing potential employer blind spots in processes of hiring and talent assessment will open avenues to access a readily available (but underutilized) talent pool. It is imperative to redefine the way that social-emotional skills are assessed to increase inclusivity of the Canadian job market. There are some promising avenues to reduce the role stereotyping and personal bias play in the assessment of soft skills. One such avenue is the approach of (PDF file) SRDC’s Skills for Success Framework (external link) , which identifies a number of strategies to reduce bias in the assessment of social-emotional skills.

Inclusive pathways to skills training

Improved assessments will only help people from equity-deserving groups if they are able to access relevant training. There are two major difficulties in providing that access. The first is that the training programs need to be targeted to provide the specific skills that employers need. Labour market data are a good indicator of the kinds of skills that are in demand. These data should inform the syllabi of skills training programs, which can then be updated as labour market needs evolve. The second difficulty is that the pathway into skills training programs needs to be inclusive and accessible.

To improve inclusion and accessibility, service providers need to be aware of the cognitive and financial burdens facing their potential participants and of how this may impact their participation in skills development programs. According to (PDF file) survey responses from over 6,600 individuals collected by the Environics Institute (external link) in partnership with the Diversity Institute and the Future Skills Centre (external link) , those who felt they did not have adequate levels of income to cover their needs were significantly less likely to report being able to find balance between work/school, household, and personal priorities; less likely to feel hopeful for the future; and more likely to report feeling depressed, compared to those who reported sufficient levels of income. In turn, people who are Indigenous (compared to non-Indigenous people), women (compared to men), and those aged 45 to 54 years (compared to those aged 18 to 34 or 55 and older) were more likely to report feeling stretched or having a hard time financially. Understanding how these burdens can hinder participation in skills development programs and acknowledging that certain groups are more likely to carry heavier burdens is crucial to designing inclusive skills development programs and supports.

Behavioural research (external link) , particularly that related to scarcity, shows how financial and mental burdens can make it more difficult to participate in, or benefit from, skills training programs. Scarcity (external link) refers to situations in which an individual faces limited time, limited income, or multiple demands, leading to worry (including worry about money) or feelings of depression (external link) , and/or a feeling of being overwhelmed. From a behavioural perspective, scarcity is important because, like an unrelenting grip on the mind, it captures our attention and depletes mental resources, leading to the neglect of important priorities, despite our best intentions. The reason for this is that the experience of scarcity leads to “tunnelling”: focusing single-mindedly on the most immediate issue or problem at hand (e.g., how to budget enough to pay rent, where to get the next meal, how to meet competing demands from family and work). Scarcity impedes the ability to focus on matters outside of the tunnel; that is, it reduces the amount of attention—or bandwidth—a person has available to make good decisions, stick to plans, and generally deal with everything else in their life. It is important to stress that the impacts of scarcity are involuntary. The impact of scarcity is not unique to or universal among equity-deserving groups; but these groups are often disproportionately impacted by scarcity.

The concept of scarcity has relevance to the design of inclusive and accessible skills training services. The question for the skills training ecosystem is how to help individuals facing conditions of scarcity—such as those unable to find balance or those feeling less hopeful—to fully engage with skills training resources. Part of the solution may lie in tailored and meaningful wraparound supports ranging from culturally appropriate services, mental health supports, access to technology, child care, or income supports for those grappling with the burdens of poverty. Although the need for these supports is abundantly clear, more work needs to be done in determining what combinations of wraparound supports are the most effective in enabling access to training and education. Broadly speaking, the tools above are all important, as is knowledge of the programs available and of key labour market information, such as the paths to employment and employers’ skills needs. It is most vital that access to programs and the presentation of key labour market information be as simple and (PDF file) barrier-free (external link) as possible.

Conclusion

As Canada’s economy adjusts to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing technological shifts, employment services have the potential to play a critical role in supporting the success of job seekers. This research summary reviews the top skills sought by employers, which are mostly social-emotional skills, and highlights a few key considerations related to reducing barriers to participation in employment programs (i.e., through the provision of wraparound supports) and the way soft skills are assessed.

Another takeaway from this analysis is that labour market information needs to be coupled with additional demographic and quality-of-life data to support conversations about EDI. Statistics Canada is leading promising work in this regard at a broad scale with the introduction of its Quality of Life Hub (external link) , which brings together key social, economic, and environmental indicators to inform decision-making. Emulating this approach of combining labour market information with an understanding of the lived experience of potential users—particularly those from equity-deserving groups—will enable the design of programming and supports that are not only impactful, but truly inclusive as well.

The journey to inclusive labour market information and skills training programs requires a coordinated effort within the skills ecosystem to meet job seekers where they are. Labour market information needs to be up-to-date and easy to access so that job seekers and skills development providers can benefit from the latest information. Employers can re-evaluate their skills assessments to ensure hiring, retention, and promotion processes are free of bias. Finally, the provision of wraparound supports—alongside good labour market information and good skills assessment—may be the combination needed to make skills training services more inclusive and more appealing to users.

Table data sourced from Vicinity Jobs (external link) Hiring Demand Analytics Suite.

Authors:

Yuna Kim, Senior Research Associate, Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University

James Walton, Research Associate, Diversity Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University

Labour Market Insights

A research series by the Diversity Institute

Reports in the Labour Market Insights from the Diversity Institute series cover a variety of topics relevant to the study of labour markets and are based on analyses of collated data from online job postings across Canada, as well as other traditional and innovative data sources. This project is funded by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Centre (external link) .