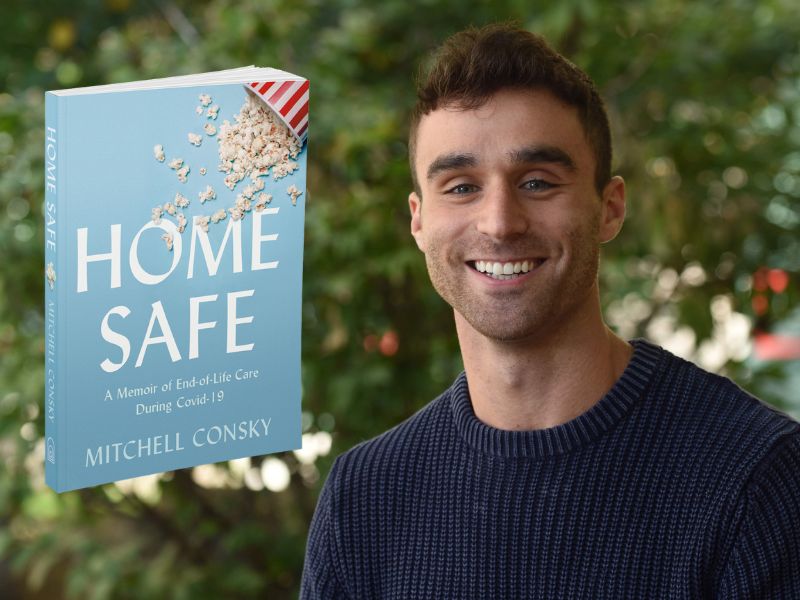

‘The inclination to save him and the obligation to let him go’: Q&A with alum Mitchell Consky, author of “Home Safe”

MJ alum Mitchell Consky (external link) started writing “Home Safe: A Memoir of End-of-Life Care During COVID-19 (external link) ” when he was collecting journal entries and audio recordings throughout his father’s decline.

What is the backstory behind writing this book?

It started off as journal entries and I really wanted to audio-record him throughout everything. He [Consky’s father] was diagnosed a few weeks after World Health declared an international health emergency. I abandoned my Toronto apartment, and I moved into my parent's house. There was just this urgency to capture what I knew I was going to lose soon. I think most of us are aware that our parents are going to die at some point in our lives and it's something that I've always thought about.

When it was happening, I was blessed with this rare opportunity for the entire world to shut down. Yes, that was scary, obviously, for all the reasons that the pandemic made everything so scary, but it was also a blessing because I was able to stop and slow down and spend more time with my dad than I think I would have been able to if the pandemic wasn't happening. So it started as just audio recordings, and journal entries, and then I wrote this piece in The Globe and Mail. From there, there's a literary agent that I've been in contact with for years. I eventually told her that I have more written on the topic and she encouraged me to send her more stuff. I grabbed all these journal entries, and all these audio recordings and I pushed them into the book. That's what it became.

How did you decide what to include? Was it a difficult process?

It was a lot of consulting with my family afterwards. This is such an intimate book, it spotlights my family and some of our darkest moments. There's a lot of joy and happiness, but this was a really sensitive period for my whole family. A lot of the process in deciding what to keep and what not to keep was getting notes from my family. I wrote an initial draft and then I sent it around to my family. They told me what they would like me to include and what they wouldn't like me to include.

In all honesty, it taught me the struggle of writing about family, and especially writing nonfiction about family. I don't know if I'm ever going to do it again. A lot of it was sort of a consultation process with my whole family.

How has writing this book changed your outlook on life?

I think we all are aware of the fact that we're gonna die and that our family and close people in our lives are gonna die. Being confronted with the actuality of that definitely offers a lot of clarity. As I write about in the book, I also lost a really good friend in a motorcycle accident. Since then, there has been this acute awareness of the inevitability of death. I think that those ideals of trying to squeeze out as much of life as possible were accentuated as my father was dying, as we were approaching the end game. I write a lot about these moments of joy, and moments of beauty that were able to emerge, despite the fact that we were accepting the end. I think that that says so much to what end-of-life care could be, but also what life can be in general.

I think that we don't have to wait for somebody we love to be dying to ask these, personal, intimate questions. We tend to look at our parents like they're just parents, and we forget that they were children too once. We forget that they've gone through their own trials, their own difficulties. I knew that my dad lost his parents when he was young, but he never really was able to speak about that until he was dying himself. I think if there's a lesson here, it's that we should be willing to have these conversations before time expires and before it's too late. That's something that I've been thinking about ever since for sure.

Was there a story from your father that you didn’t expect to hear?

When the scenes where I'm recording him, and I'm talking to him, I got his answers, but at the beginning, at least, they were very surface level, and he would give me fragmented details. A lot of this stuff was actually in follow-up interviews after my father died with his two siblings. I knew that my father lost his father when he was 22. He lost his mother when he was 15. My dad had told me this, but I didn't know until afterwards, that his father died when his family wasn't around. They were praying at a synagogue and their father died and you know. To me that offers such an interesting contrast to what my father experienced, they didn't get to hold his hand until his last breath, whereas my father until his last breath, he was surrounded by family surrounded by love. There were photos of family pictures, plastering the walls, and there was that article that I wrote, pinned next to his bedside.

I think we're all gonna die someday, but not all of us are going to die, surrounded by all the people that we love, all the people that we care about. An important juxtaposition to consider is the fact that so many people didn't get that throughout the pandemic, they died in isolated hospital wings with nothing but masked nurses, attending to their every breath. To me, it shows how lucky I was and how grateful I should be that we were able to have this home hospice and that we were able to spend every single moment until his last breath.

What made you want to include the perspective of health care during COVID-19 in the book?

Something that's interesting about my family is that the majority of us work in health care. In my extended family, there are three emergency physicians, a couple of social workers, a general surgeon and neurologist and a nurse. So when the pandemic struck, they had to navigate their frontline obligations with a family-based approach to end-of-life care. It's not that this is just a story about a family taking care of a dying loved one. It's very much a family of healthcare workers taking care of a dying loved one. That opened my eyes to a lot about what medicine currently stands for, and areas for improvement. I thought it would be important to mention the fact that my family was healthcare workers because they were also juggling these opposing perspectives, there was that inclination to save him, and then the obligation to let him go. I think that that was a difficult thing for us to truly reconcile. In doing that, we were able to bring so much meaning to the end of his life.

How was the experience for your family?

In the beginning, it was difficult merely for the distance factor and the fact that they couldn't come into the house. So my current brother-in-law, for instance, was going into the hospital every single day. My sister who was living with him, at the very beginning, was going into her hospital too. Every time they came home and hung their scrubs up or threw them into the wash, the risk of exposure was reintroduced. So because of that, they weren't able to be together at first and then also my sister wasn't able to come home.

Eventually, what ultimately ends up happening as the book describes, is we create this sort of bubble, this hospice at home where we had this open door policy, and the doctors and my family were coming in, throughout all hours of the day and nights. The thing with my father is that it was only seven weeks from diagnosis to death. The home hospice aspect, the parts in which we accepted the fact that he was going to die and that his treatment wasn't working, that was almost for two weeks, maybe less than two weeks of us understanding that. They were able to pause their frontline medical obligations and come in and help to the best of their ability.

Other than that there was also, my cousin Daniel, and the other doctors, my family, they had this urgency, they wanted to help, they wanted to do something. That was their medical inclination. That was their desire to fix a problem and they could only stand by, they can answer questions and they can do some research, but I think that they felt helpless. I think they felt there was nothing that they could really do. The experience I believe offered them an intimate and intimate perspective of what end-of-life care could be and the opportunities that it can hold.

What do you hope people take away from reading this book?

It's important for me to convey that for people that haven't read this book, it's not just a sob story. It's not just this traumatic experience that happened to me, I do believe that there's joy, and there's beauty. It's not just a story about sadness. The fact that we had all these moments, we were able to have these pyjama dance parties, and we were able to hear my dad's awful jokes, binge-watch Netflix and be together in the shattered world.

There's hope in this story. I hope that they can realize that there's a great relief that can come with accepting the inevitability of dying, leaning into the dialogue about death and grief, and leaning on your family to get you through these difficult times. I hope people can realize that it's a story about all that as much as it's a story about loss.

Join Consky at the Home Safe Book Launch event (external link) to hear a public reading and get a signed copy, on Nov. 1 at 7 pm.