Can Toronto Multiplexes Help Save the Greenbelt?

Photo of 401 Highway within Ontario Greenbelt by Haljackey courtesy Wikipedia, Creative Commons license.

Last week, Toronto City Council approved a new “multiplex” policy, allowing duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes to be built in every residential neighbourhood city-wide. The Multiplex policy joins its Missing Middle cousins, laneway and garden suite programs introduced over the past couple years as part of Toronto’s Expanding Housing Options in Neighbourhoods (external link) initiative.

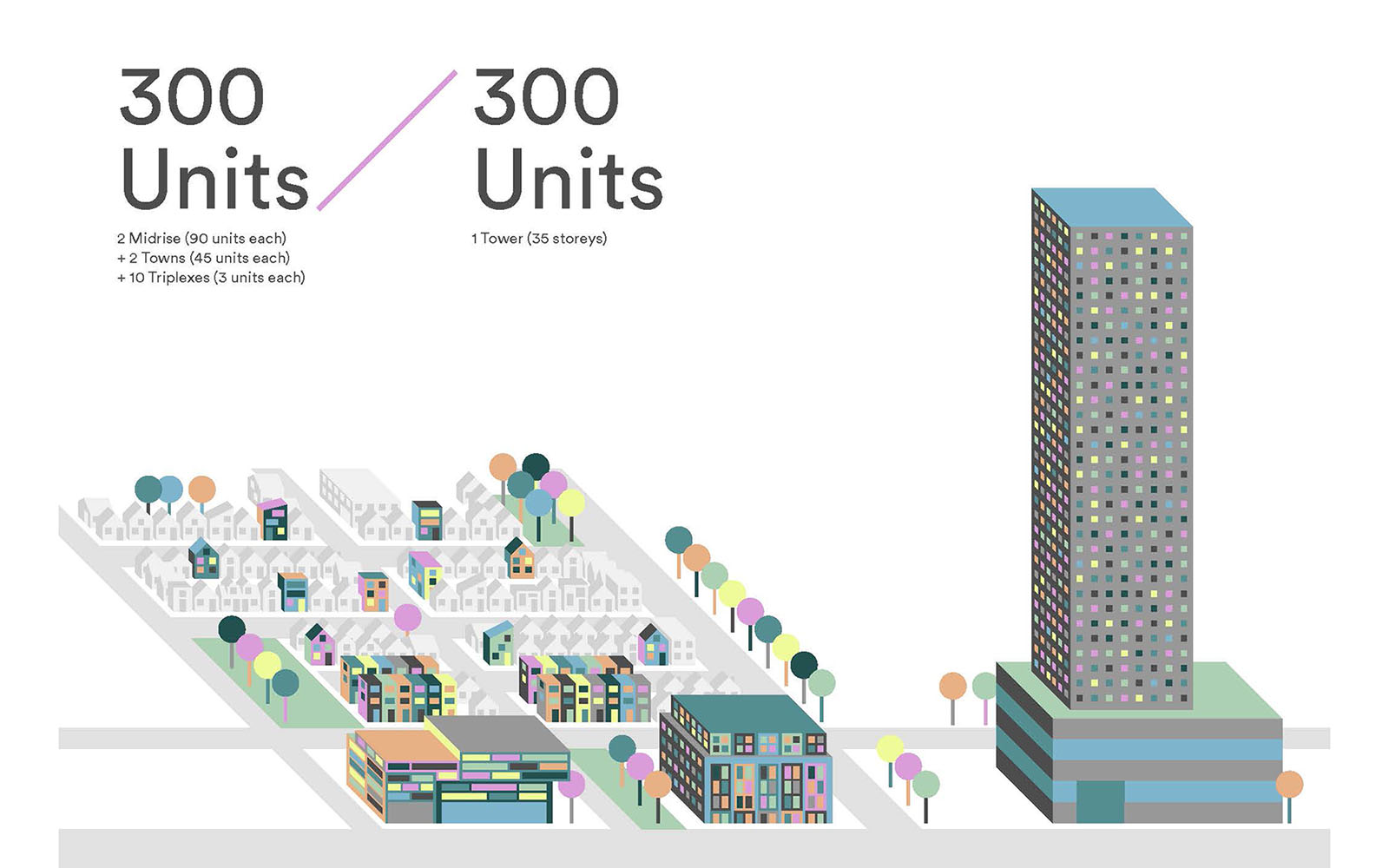

This is a big deal. Until now, about seventy percent of Toronto’s entire residential land base has been restricted to detached or in some areas semi-detached houses. In a housing crisis, that’s a lot of under-utilized space. With so much land off-limits to anything but single-family homes, Toronto spent the past two decades cramming new housing in the form of condo towers onto a very small portion of the city’s land designated for intensification. For example, the Downtown and Central Waterfront area accounts for only 3.4% of Toronto’s total land base, but contains 36.6% of all residential units that were in the development pipeline from 2014 to 2018. In the same time frame, another 10.5% of all new residential units were proposed or built in Toronto’s four growth centres (Yonge-Eglinton, North York, Etobicoke and Scarborough), and 21.5% along designated Avenues.

Years of outdated zoning policy is reflected in our built form – a sea of single-family homes interrupted by spiky spines and clusters of tall condos. But what does this have to do with the Ontario Greenbelt? After all, Toronto ran out of greenfield land for outward expansion many decades ago, and has had no other choice but to build up and in. It’s other municipalities in the region that are still sprawling, right?

Years of outdated zoning policy is reflected in our built form – a sea of single-family homes interrupted by spiky spines and clusters of tall condos. Image courtesy Unsplash.

Toronto, and all Ontario municipalities, have a role to play in tackling urban sprawl by (PDF file) doing density right, distributing it throughout our urban footprint, making density livable, more affordable and inclusive. There is a common saying among planners, housing experts and policy makers: the only thing residents hate more than urban sprawl is urban intensification, referring to the strong NIMBY (“Not In My Backyard”) who opposes neighbourhood developments.

Tall condos have an essential role to play in our housing system, providing much-needed housing supply, and they are vital along transit lines and at stations to encourage transit ridership as well as walkability in our urban centres. However, if most of what gets built in growing municipalities like Toronto continues to be small units in tall condos, this can exacerbate urban sprawl. Home-seekers in Toronto face dismal choices: a single-family home’s average sticker price currently ranges between $1.5 and $2 million, and the other option is a small condo unit, which is not suitable for all household sizes.

A recent analysis by journalist Matt Elliot shows that while the number of condo units squeezed into condo projects in Toronto has increased, the size of the units in 2021 shrunk by 200 SF to an average unit size of 614 SF. This isn’t limited to the 416; an analysis by the City Building Institute and Urbanation in 2017 examined the five-year condo pipeline for the entire GTA and also found a trend in diminished unit size, a decline in units of two bedrooms or more, and an increase in building height.

Thus, hopeful buyers chase new single-family homes in far-flung bulldozed farmland as the only attainable family-friendly housing option. To this effect, new provincial OPAs mandate municipalities to expand their boundaries (external link) to enable new subdivisions. These actions, along with opening up the Greenbelt and pushing through new highways to facilitate sprawl are truly the opposite of what is needed to address climate change (external link) and housing affordability, especially if you factor in the transportation costs home buyers must bear in car-dependent locations.

The Missing Middle might represent our region’s best hope to combat urban sprawl and related GHG emissions associated with urban sprawl such as the large energy inefficient houses, which consume twice the energy as compact homes, and the increasing number of cars and trucks on the roads to service these car-dependent landscapes. More spacious “ground-related” Missing Middle housing could provide the closest alternative to sprawl houses, and these new homes – be it a fourplex or a basement suite – don’t involve choosing between houses or farmland, as they are added to neighbourhoods that already have municipal infrastructure, roads and transit, health clinics and schools, thus saving municipalities (external link) a bundle.

Illustration from the report Density Done Right, published by the City Building Institute in 2020. See our page News & Research (opens in new window) to download the report.

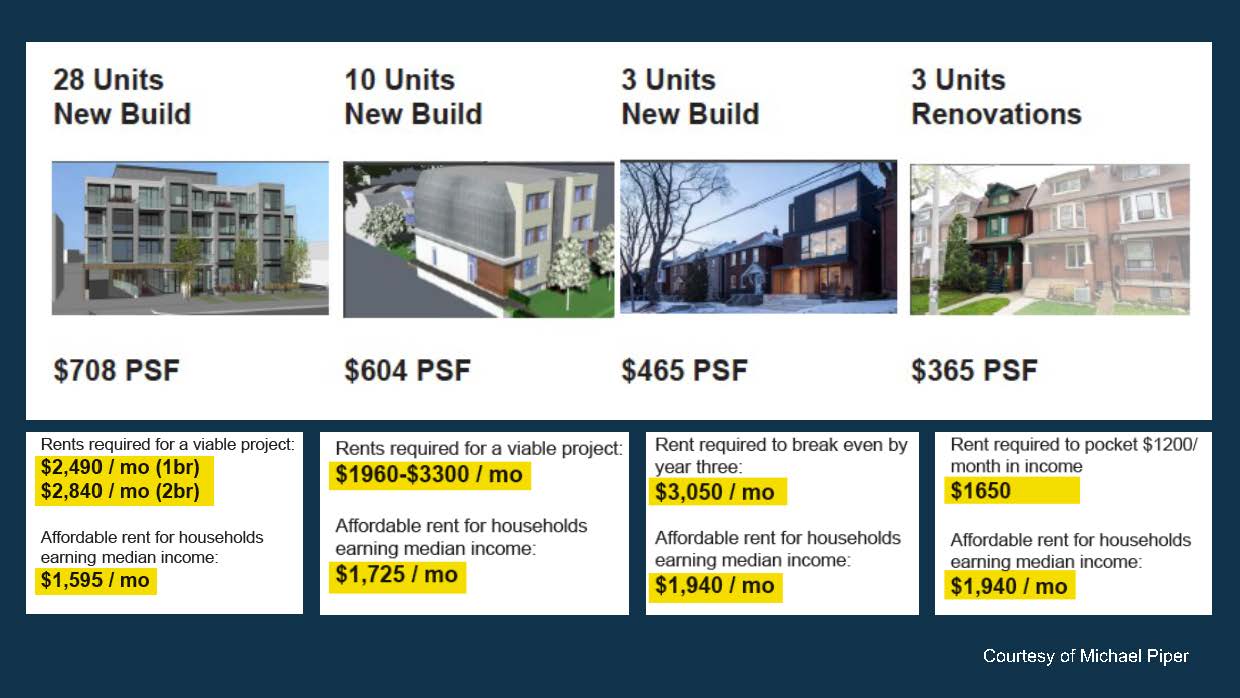

We need both – the condos and the Missing Middle – but we need choice, and we need it fast. Now that multiplex policy has been approved, the hard work comes next. The challenge is making this housing affordable, or at least “attainable.” There is (PDF file) early evidence (external link) that current approaches to building multiplexes produce market-rate housing. While Missing Middle programs have been rolled out in many municipalities and zoning has been changed, the uptake by homeowners has been disappointingly low due to costs and the onerous process. For example, Toronto and Los Angeles are comparable in population, yet LA has seen 10,000 ADUs built in five years, while Toronto has seen fewer than 50 laneway homes completed to date.

Moving Quickly and Affordably with the “Missing Little”

According to a report by ULI Toronto, it is faster to scale housing supply throughout our neighbourhoods with Missing Little instead of converting/constructing a new building, and it is most cost effective to address affordability and equity in neighbourhoods by adding units to an existing home – not demolishing it. In Toronto, adding one unit to 15% of single-family homes would be equivalent to building 100 condo towers. California, through coordinated efforts, achieved 20% of the State’s total new housing supply (external link) through secondary suites added to single family homes over five years.

With an effective well-resourced municipal program, supported by the Federal Housing Accelerator Fund (external link) , Missing Little housing has the potential to be the faster method of delivering new, more climate-friendly housing supply.

Missing Middle housing has long been championed as a solution to housing affordability and sustainability by planners (external link) , homebuilders, advocates (external link) and urban thinkers (external link) alike. We now have many tools to slice and dice the Missing Middle. Zoning is no longer the key obstacle to adding residential housing. Second-generation barriers (outdated building and fire codes, suburban street parking restrictions, etc.) still need to be busted, along with other challenges to update, such as what’s in it for the homeowner. Our next mayor needs to bring fresh thinking and creativity to this file and understand how getting this right is critical to building the type of supply the city – and the region – needs.

Original image by Opticos, with additional sketch showing "Missing Little" housing types by Michael Piper.