Yellowhead Institute’s Land Back report delivers devastating critique of land dispossession in Canada

Artwork by Julie Flett (from) A Day With Yayah by Nicola Campbell. Published by Tradewind Books.

Numbers don’t lie. Neither do maps.

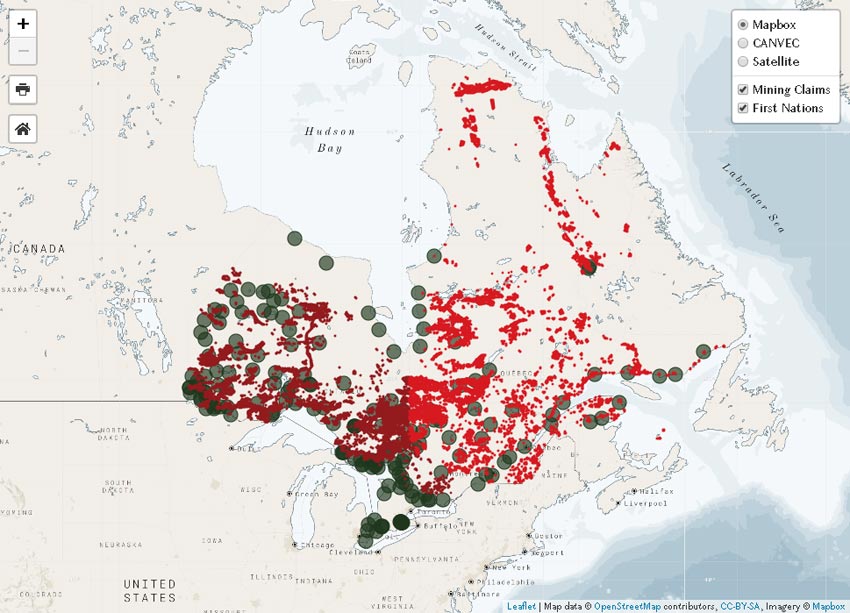

Last fall, Canada’s first Indigenous-led think tank released (PDF file) Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper (external link) , a report that unearths the history of land dispossession in Canada and the impact this has had on Indigenous people – particularly women. A map of Ontario and Quebec included in the report’s online version is blighted with blood red specks, revealing the scale of resource extraction in Canada’s two largest provinces.

“I think it’s a remarkable graphic depiction of how much land has been alienated from Indigenous people through mining exploration and development,” says Hayden King, executive director of the Yellowhead Institute.

The struggle to reclaim jurisdiction over huge swaths of land is a central demand for Indigenous people in this country. The Land Back report delivers a critique of the judicial environment that allows governments and corporations to “legally” steal historically Indigenous territory, and the effects that this has had on their communities.

(external link)

(external link)

Mapping the overlap between mining claims (red) and the presence of First Nations (green) shows the extent of fragmentation of Indigenous land caused by resource extraction. Click on the map to learn more. Courtesy of The Yellowhead Institute.

Land alienation and economic growth are interconnected. Statistics detailed in the report illustrate the size and extent of Canada’s natural resource sector:

- Canada exports $81.4 billion worth of minerals and metals per year – over 20 per cent of our national exports.

- The forestry sector alone accounted for 186,838 jobs in 2017, contributing $24.6 billion to GDP.

- Natural resource sectors accounted for 84 per cent of total water consumption in 2005.

Court injunctions and First Nations

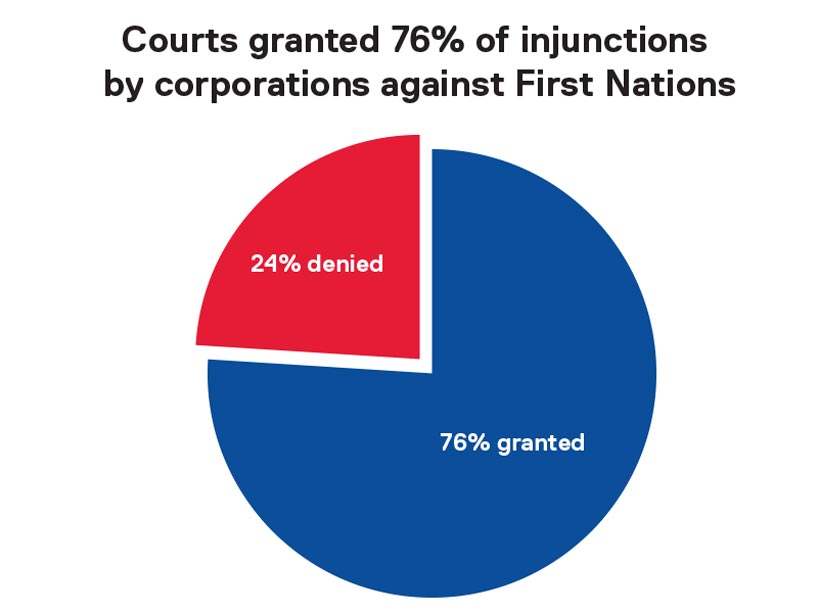

In reviewing over 100 cases of injunctions, court orders that restrain someone from doing something, Yellowhead researchers found that 76 per cent of injunctions filed against First Nations by corporations were granted. Conversely, 81 per cent of injunctions filed against corporations by First Nations were denied. Furthermore, 82 per cent of injunctions filed against the government by First Nations were denied. This means that 4 times out of 5, the courts side with corporations and government rather than Indigenous claimants on land use cases.

After reviewing 100 cases, researchers found that corporations were granted injunctions against First Nations 76 per cent of the time. Source: The Yellowhead Institute.

“I suspected that we were going to find that First Nations were losing injunctions at a high rate, but I was pretty blown away by the staggering discrepancy in those figures, that overwhelmingly corporations and governments succeed in serving injunctions against First Nations, and First Nations lose in the courts,” says Yellowhead Research Director Shiri Pasternak.

Power imbalances between First Nations and well-financed companies mean that while the former must commit to lengthy, costly litigation to protect their land and waters, the latter can gain an injunction at the mere prospect of economic loss.

Land dispossession and its profound effect on Indigenous women

After Indigenous people were uprooted from their lands and forced onto reserves in the 18th and 19th centuries, they lost significant control over their land. Even in today’s legal environment, where the courts have determined that the government has a duty to engage with First Nations when their constitutional or treaty rights may be affected by the state, consultation is often equated with consent.

Yellowhead researchers argue that court injunctions are used to override Indigenous Peoples’ lack of consent to develop their lands.

“What we’re suggesting in Land Back is a movement from a principle of consultation, which the courts have required governments to pursue, to a principle of consent, which the international community and Indigenous Peoples have endorsed,” says King.

“Right now we have this gulf between consultation and consent that we hope can eventually be bridged,” says King.

Land dispossession has had a negative impact on Indigenous women in particular. European settlement broke down traditionally strong female authority in society, replacing them with male-dominated systems of governance. Misogyny remains a legacy of colonization.

“Violence against the land and violence against Indigenous women’s bodies are deeply interconnected,” says Pasternak.

Furthermore, in resource extraction industries the phenomenon of “man camps” – temporary bases for male employees of construction projects in remote areas – make worse gender-based violence. Their presence has been linked to various forms of sexual assault.

Cities, land and legitimacy

Pasternak believes that Canadians aren’t properly educated about the history of colonization in Canada and Indigenous law. One fact not often discussed in the media, she says, is that there are already laws governing land tenure and jurisdiction in Canada.

“People don't know about the long court struggles. They don’t know what Indigenous people have won in the courts, and that Canada has tried to roll back those wins,” says Pasternak.

Protests led by Wet’suwet’en Nation against the $6.6-billion Coastal Gaslink pipeline project in Northern British Columbia make the Land Back report’s findings even more important.

Though the report discusses land dispossession happening in areas far from Toronto, the authors believe that the report’s findings are relevant to people who live in major cities.

“While we think of rural areas as peripheral to urban centres they actually are central to the production of urban life, in terms of all of the raw materials we all depend on in our lives, such as oil and gas, timber to build our homes, the hydroelectric power generated by massive electricity stations and so on, we’re actually deeply interconnected with land outside of cities,” says Pasternak.

King points out that Ryerson University itself occupies a large chunk of land.

“I think that there are questions about what Ryerson can do in terms of Land Back and working with Indigenous partners to make sure we’re not gentrifying the neighbourhood and we’re not pushing people – especially Indigenous people – out of their homes,” he says.

Both King and Pasternak believe the Land Back report isn’t just relevant to Indigenous people. The legal history analyzed in the paper raises questions about the country’s policies towards Indigenous rights and land tenure.

“We are the subjects of a colonial government and Canada does things in the name of their citizens so it’s up to us to hold our government accountable for the values that we want to embody,” says Pasternak.

The Yellowhead Institute gratefully acknowledges the Land Back report was made possible by the support of the Laidlaw Foundation and the Faculty of Arts.