Listening to Rice

The shifting, encyclopedic knowledge of our ancestors, at times leaking truths that modernity conceals.

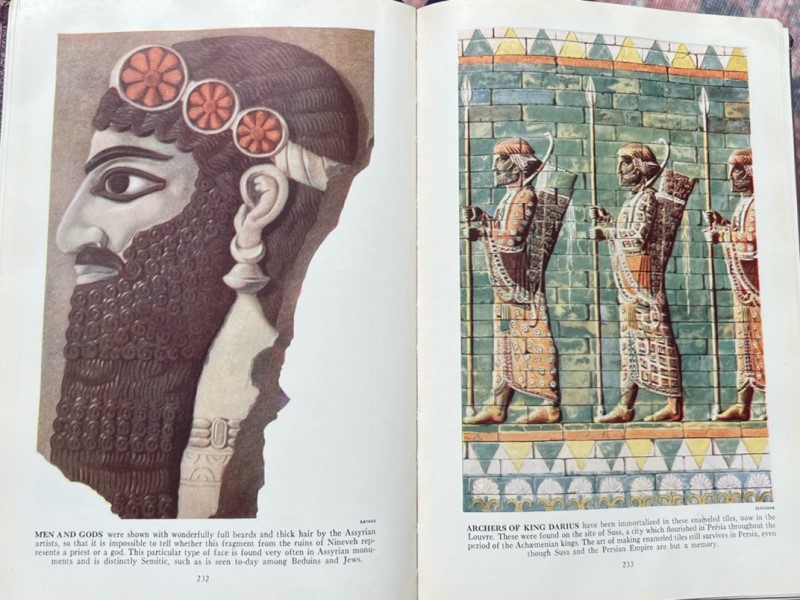

Image: Open page from the encyclopedia ‘Lands and Peoples’, published in 1957 (The Grollier Society). Photo Credit: Sahar Te.

I have too much on my mind but not enough on my tongue these days. So, I’ve been writing! Far more than I knew I could. Out of necessity, urgency and frustration.

I’ve been reflecting on why I write. I edit films, which is another form of writing. Both practices shape my life and my PhD. Here, I want to bring them closer to one another.

There is so much content in the world. Technically, everything has already been said. Yet within academia and the creative industries, more is being said than heard.

Things have been said yet not heard.

Things have been said but not translated.

Things have been said but intentionally discredited, not cited, and not noted.

Things have been lived.

What often strikes me now is that new terms and methods merely rename experiences that have long been lived by others: by Buddhist monks, Sufi dervishes, Indigenous elders, Palestinian mothers, cowboys, farmers, prisoners, slaves, taxpayers, butchers, bakers, bartenders, DJs and graffiti artists.

Anthropologists coin concepts that Black farmers have embodied for generations. Media theorists devise methods practised by Middle Eastern children role-playing television crews. French philosophers publish ideas first voiced by Islamic thinkers five centuries ago. Economists praise critical strategies long upheld by Indigenous communities.

My grandfather spoke of all this long before I knew Edward Said or Gayatri Spivak put it into print. He would say it over lunch while listening to Voice of America misrepresent the film industry’s account of the Battle of Thermopylae.

Many scholars have yet to discover insights and analysis shared around our own tables, while pouring stew on rice, worth far more than any credited source.

How do you measure rice for twenty-eight people? My grandmother simply eyeballs it.

I used to write in reaction or response, in dialogue with a cause, a topic or a perspective, out of care, anger, necessity, solidarity, love or curiosity.

I wrote to defend, to clarify, to counter, to engage or disengage, and to agree or disagree.

Lately something has shifted. I write in a new way, and something strange has begun. I am discovering something I always knew was there. It arrives like a visitor. It takes me by the hand and we go on walks together. This thing that writes is me, yet it feels both unfamiliar and more me than ever before.

The more I do this, the more I hear a voice within that is intensely social, collective and communal. There is grief and celebration. I type, and as I encounter each word, I write without seeking resolution or a fixed outcome. The words form ripples, circles and spirals. They entrance, dance and invite. I cannot call them poems or academic writing, yet they inform both my creative and scholarly practice.

Trust grows. I trust what is being said, to me and to everyone. I used to be terrified of this voice. I still am at times. I sometimes stare at a trap growing before my eyes, inviting me to psychoanalyse, to deconstruct, to seek and to edit. I believe there is something I call ‘the scholar’s gaze’. As an academic, a scholar and a writer—any label that separates modes of being—I have now found a different way of being. It shapes my research, my writing, my curiosity and even how I make tea, cook rice or brush my hair.

I love rituals, collective and personal. Most academic rituals feel unidirectional: gathering data, collecting, writing about, numbering and analysing. It seems to me that the self becomes centre stage—important, in control and in charge. In that posture there is licence and audacity. What I am saying here is about my own voice. I am not speaking for anyone else.

How do I remain an active scholar while allowing other ways of being in the world, practised widely though rarely taught as methods, to enter my work? Ways that can be respected, nurtured and invited as rituals, and as knowledge.

I write this from the moment I pour water onto rice until it has evaporated. I listen for the bubbling to slow, then I cover the pot and let it simmer. Growing up in a cuisine centred on rice, I have met many who treat it as a precise science, anxious to follow recipes and measurements to the letter. I never studied this craft, gathered data or measured anything. I grew up with intergenerational knowledge transfer, an embodied understanding and an improvised relation to the world, and it has always worked. In that process I am not rejecting established methods. I am discovering my own surrender, my own rhythm, my own trust and my own encounter with the world. I have yet to taste rice better than my grandmother’s. The secret does not lie in measurement but in the way she listens to the rice. The rice speaks to those who listen, and those who eat it learn to trust how it was made.

Sometimes relying on strict measurements and predefined methods reflects a lack of trust in what the world can teach us. I’ve learned that humility, not certainty, is essential to my research. After all, methods are grounded in lived experience and rooted in listening to the rice.

Rice will cook in different ways, with different formulas, in different places and for different intentions. Each ritual will yield a distinct flavour.

I like the taste of rice this way.

About the author: Sahar's research explores the intersections of literature, culture, and politics within the context of the Iranian diaspora. Her interdisciplinary approach combines literary analysis, feminist theory, and postcolonial studies to deepen our understanding of how diasporic identities are constructed, communicated, and mobilized in pursuit of social justice and collective empowerment.

Insights & Ideas is a ComCult blog series showcasing the research and expertise of ComCult students. Designed to engage a broad audience, the series features op-ed-style posts that connect academic insights to real-world issues, making complex ideas accessible and relevant. Each entry highlights the unique perspectives and innovative thinking within the ComCult program. We invite you to explore more stories that amplify research and inspire ideas! (News and Events Archives)