Kenya is set to achieve clean energy for all – can other countries too?

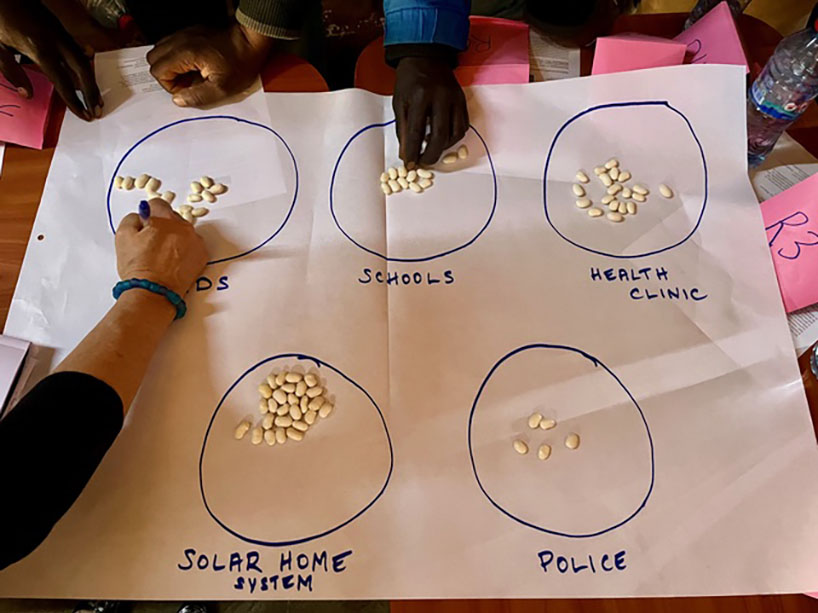

Focus group participants discuss how they would allocate the national budget to citizen energy needs with Christopher Gore, TMU professor and researcher. Photo by: Elizabeth Baldwin

Climate scientists continue to sound alarms over the rate at which the world is warming – in fact, NASA officially declared 2023 the warmest year since global records on the earth’s temperature began in 1850.

With the window to respond effectively narrowing each year, TMU researcher and professor Christopher Gore has just returned from a SSHRC funded trip to Kenya. The International Energy Agency expects Kenya will achieve the U.N. Sustainable Development Goal 7 - Affordable and Clean Energy For All by 2030.

Gore and his research team – which includes collaborators at the University of Nairobi, Indiana University, the University of Arizona and Northern Illinois University – have been researching whether Kenya’s model is something for other countries to mimic, and how the model has improved or complicated the economic and social conditions of households in several Kenyan counties. This move toward green energy that Kenya is going through reveals some challenges in addressing climate change through energy policy.

As a PhD student, Gore made his first visit to Kenya in 2000, when he was investigating environmental policy. “I visited both Kenya and Uganda at the same time, and at the time, both countries had dismally low supplies of electricity,” he says. “In Uganda, below 15 per cent of the population had electricity, and in Kenya about 20 per cent of the population had access to electricity.”

In 23 years, Kenya has rapidly shifted the country’s approach to energy generation: now, 90 per cent of the electricity generated in Kenya comes from green sources and almost 80 per cent of the population has access to some form of electricity in their household.

“The president of Kenya has argued that it’s an example of how African countries can leapfrog fossil fuels and completely produce all the energy they need through green sources,” says Gore. “What we're trying to do is understand whether Kenya is a model that other countries can follow and what the implications of the approach is for well-being at the household level.”

Kenya’s unique model

Gore stresses that Kenya’s shift in energy provision has been both for proactive and reactive reasons.

“Kenya was open and willing to experiment with different energy provision for a number of reasons, including energy shortages and droughts that lead to low supply from hydroelectric dams,” he says.

When Kenya started to see energy shortages as far back as the 1970s, they began looking for alternatives to hydroelectric production and fossil fuels. “They have resisted the push to build coal power plants, which they’d considered for some time,” he says. “But that's based on a couple of very favourable conditions: they have geothermal electric power that other places don't have.”

Now, climate change is making diversified energy provision in African countries a near necessity. “Global climate change is having a detrimental impact on the capacity of African countries to rely on things like hydropower,” says Gore.

So while Gore and his team see potential in Kenya’s model to achieve a clean energy grid, he points out that the international community has to recognize the particular conditions established decades earlier in Kenya that can't be quickly replicated in other countries.

Gore’s research has involved household to household surveys, to discover how Kenya’s increased access to energy has impacted citizens. Photo by Christopher Gore

Gore’s research methodology and findings

Gore and his team have been conducting a multi-phased study using qualitative and quantitative methods, which include phone surveys, household surveys, focus groups and interviews, to understand how households are using energy and how it’s changed lives. The survey team worked in both rural low-income areas and urban spaces to achieve as representative a sample of access to electricity as they could.

Through the surveys, the research team has gained some surprising insights into how this energy provision model is working on the ground – and what challenges people are facing.

One major benefit Gore heard over and over was access to electricity has improved simple things like security. “Many women said that having lighting, they just felt much more at ease,” he says.

Other benefits include the fact that people with small businesses have been able to stay open longer, improving their business outcomes. Residents also noted improvements to air quality, and they had more access to information through radios and televisions.

Focus group participants show how they would allocate the national budget, comparing subsidized solar home systems with other needs. Photo by Christopher Gore

But Gore and his team noticed some important social changes from greater access as well.

“When people have electricity, they don't go out as much because they can entertain themselves,” he says. “So there’s been impacts to social engagement as well as political engagement.”

And, cost continues to present challenges. “Some people can’t afford to get a simple connection to their household. There are innovative micro-financing systems where you can pay a daily rate for a small solar home system, but as soon as you get access to a little bit of electricity, you tend to want to buy more appliances and there are lots of challenges with gaining access to more supply,” says Gore.

Challenging the global narrative around climate change

This project in Kenya gives Gore an opportunity to focus on energy justice, something we should all be considering, he says. “There’s this amazing tension between celebrating the value of green energy access and moving away from dirty fossil fuels, while being very mindful of the fact that this doesn't come without major limits and challenges,” he says.

“Why is it that a country like Kenya – which makes very little impact on global climate change – should rely on systems that are potentially unstable or not necessarily sufficient to meet demand while other countries that have relied on fossil fuels have a steady supply of power?”

At the household level, Gore says his research team noticed that the population wasn’t thinking about the relationship between climate change and energy production. “Transitioning to green energy choices is purely pragmatic, they're only thinking about their energy reality.”

And the demand for energy supply is only increasing. “Ultimately, they want as much access to power and electricity as everyone else does,” says Gore. And even though Kenya is on target to meet the U.N. SDG target of ‘Energy Access for All’ by 2030, there are still large improvements to be made to increase and improve household access.

What’s ahead

Gore and his team are analyzing the data they’ve collected from their last trip, and will return to Kenya in another six or eight months to share the results with the survey respondents, focus group participants, Ministry of Energy, the African Development Bank and with colleagues and connections at universities in the region.

“Then we hope to expand this work and take the lessons we learned in Kenya to other countries. Energy access is a problem all across the continent, so our hope is to apply for new research funding and to bring in other partners from countries across the continent.”

For Gore and his research team, Kenya is a pilot study to try to understand what's taking place in their green energy transition and see how it might differ for other countries. “If we want to see these extraordinary outcomes in other countries, it's going to require massive investments in green energy technology as well as transmission and distribution networks,” he says. “And if there isn’t, then of course people are going to choose the energy sources that are the cheapest available to them.”

Related stories: