Fighting for equal rights for LGBTQ2S+ community

Pride month is a time to reflect on the struggles for equality and the fight for social justice as much as it is a time to celebrate our differences. Professor Alison Kemper has been on the frontlines of the LGBTQ2S+ movement for almost 40 years. Photo credit: North 128 via Pexels

As a church minister in the early 80s, business management professor Alison Kemper, along with her partner, Joyce Barnett, also an acting minister, decided they couldn’t continue working in their parish and be closeted about their relationship.

By not being able to live authentically as a couple they wouldn’t be able to move forward with their lives and have a family. “Being in the closet within the church was terrifying. You could lose your job and your housing overnight,” Kemper says.

Today, Kemper wants to remind younger generations that it wasn’t very long ago that protections did not exist in the Human Rights Code for sexual minorities. “We have to keep fighting, we can't take our rights for granted,” she says.

The struggle for recognition

“The experience turned us into queer activists with nothing to lose.”

Kemper and her partner Barnett bought a house on Pride day 1985 at the same time that Barnett fell pregnant with their daughter. They began to look for a queer-positive church that would accept them as a family.

She had been invited to preach at Holy Trinity at the end of October 1985, a parish she knew was committed to social justice and accepting of gay and lesbian congregants, and expressed their desire to find a welcoming congregation. They told the parish they did not want to hide for fear of persecution any longer, and the parish embraced them.

Although their church was accepting, they were very publicly ‘outed’ in 1986. The Archbishop, Lewis Garnsworthy, who was alerted by someone in their parish, inhibited the couple from functioning in the Anglican church for violating the church’s morality standards, an action that was covered in news media around the world. The scandalization of their relationship took an exacting toll.

“These were cruel, horrible and real experiences of discrimination within the church, and not theoretical. After Joyce and I were thrown out of our orders, we later found out that we had been placed on a list of clergy that included child sexual abusers. People stopped talking to us. The homophobia was real, it was present and it was active.”

However, far from silencing them, the incident radicalized them. “The experience turned us into queer activists with nothing to lose.”

The early struggles

In the 1980s it was very rare for employers to extend health care benefits coverage to same sex partners and their children. Working for small immigrant women's agencies under the United Way, Kemper fought to have the United Way extend coverage to all its umbrella agencies, and update stipulations in their anti-discrimination code.

“Before there was any notion of relationship recognition there were some real hard pushes towards inclusion into the Human Rights Code, but they hadn't come to fruition yet,” she says.

Even though she succeeded in obtaining coverage for herself and her family, she met with obstinate resistance from the United Way leadership at that time to extend benefits to other agencies.

The struggle for legal same-sex parental recognition and a landmark court case

In the 1990s, while working at The 519 (external link) , a City of Toronto agency and community centre serving 2SLGBTQ+ communities, Kemper was fighting on the legal front to secure recognition for parents of same-sex couples’ children. Kemper and her partner were approached by lawyer Laurie Pawlitza, who was recruiting couples to challenge the Ontario Child and Family Law Act at that time. They were one of four couples who took up the fight.

In May 1995 they successfully won the right to adopt their own children. The groundbreaking decision made by Ontario Court Judge James Nevins reasoned that the definition of spouse under the relevant Ontario law was discriminatory and violated Canada’s charter of rights and freedoms by not allowing same-sex couples to adopt. On May 24, 1995, Ontario became the first province to make adoption legal for same-sex couples.

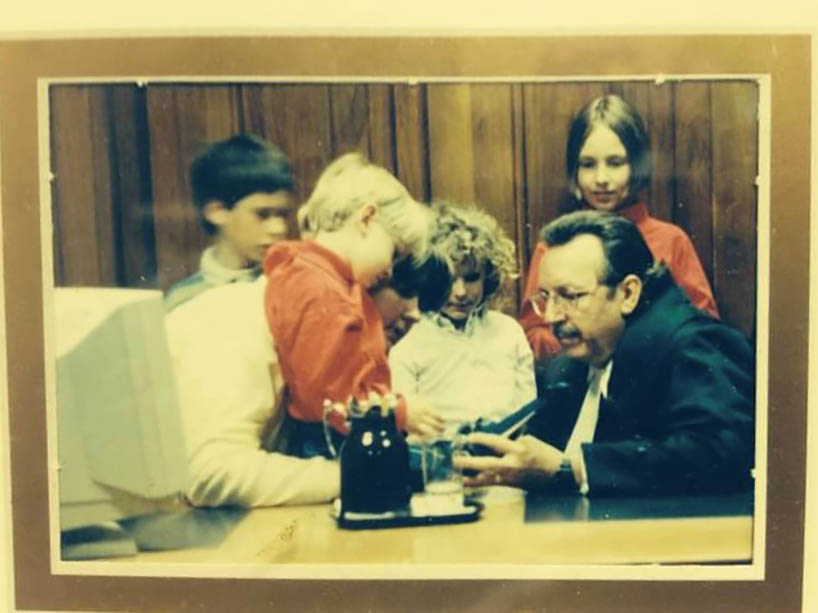

Kemper and Barnett’s young son with Alison Kemper and Ontario Court Judge James Nevins during a legal challenge to the Ontario Child and Family Law Act in 1995.

The fight for equal marriage rights

Kemper and Barnett would have been celebrating 20 years of marriage on June 13th, 2023 if it wasn’t for the tragedy of Barnett’s passing in November 2021 after a battle with cancer. After 38 years together, fighting for equality of rights, Kemper felt fortunate in Barnett’s last weeks to be able to see how far they had come together.

The road to equal marriage rights had been a long one, taken up by various people and groups at the time. In their case, lawyer Martha McCarthy approached Kemper and Barnett in 2000 as part of a legal strategy to work with a couple that had children and to argue that it was the children’s right to have their parents’ relationship legally recognized.

“McCarthy would make clear that the children's rights to married parents - permanently committed parents - were what was at stake here. It turned out to be a strategically genius move,” says Kemper.

Their children, a young son and daughter, savvy, articulate and dimpled, were enlisted in the legal challenge.

A Globe and Mail article from 2001 (external link) quotes their son Robbie, who was 9 years old, telling reporters at the inception of a constitutional challenge brought to the Ontario Superior Court on the steps of Osgoode Hall, "I think this case means no one will be able to say I don't have a real family." At 12 years old, Robbie lobbied for inclusive legislation in Ottawa in 2004. “The lawyers on the case called Robbie their secret weapon,” says Kemper.

On June 10, 2003, Ontario was one of the first provinces to legalize same-sex marriage when a decision by the Ontario Court of Appeal determined the common law definition of marriage violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which guarantees Canadians’ equality rights. Three days later, Kemper and Barnett were married at Toronto’s City Hall on June 13th, 2003. This was followed by a second wedding ceremony and celebration on September 6, 2003 at their church with 250 guests. This would be the third time they had exchanged vows.

Their first wedding had taken place in November 1984, in a very private and secretive ceremony at a friend’s home, blessed by an Anglican clergy member and ally.

“We had three very different experiences of getting married. The first was exciting and terrifying, the second was intimate and brief at City Hall. The last one was just utter triumph. One woman said it seemed like the parishioners were levitating off the ground. Everyone knew it was a massive event, and they were just excited and proud to be part of it.”

Alison Kemper married her long-time partner Joyce Barnett after a decades long struggle to achieve equal legal recognition of their family and domestic partnership. In June 2003, Ontario was one of the first provinces to legalize marriage for the LGBTQ2S+ community. The federal government followed in 2005.

We feel a new sense of equal dignity and acceptance in our community… we are theoretically fully equal persons. We have the same fundamental rights as other citizens, including the right to choose marriage… We feel that our relationship now has equal respect and consideration.

Gender identification becomes embedded in human rights

In 2000, Ceta Ramkhalawansingh, a former city councillor and advocate for human rights, invited Kemper to contribute to the development of new human rights contract compliance regulations for the City of Toronto. Kemper suggested the inclusion of gender identification, which was a relatively unknown term at the time. Ramkhalawansingh readily accepted the suggestion, and the inclusion of gender identification was recognized in the new policy framework.

“She sent this to me and I thought, ‘Oh my god, we could put gender identification in there’, and because almost no one on the city council knew what gender identification meant in 2000, it just sailed right in.”

This seemingly minor language change had significant implications. For instance, it meant that organizations like the Salvation Army could not discriminate against transgender individuals without homes if they wanted to continue receiving funding from the City of Toronto.

Against the backdrop of the HIV/AIDS crisis

An important aspect to their story, says Kemper, is the LGBTQ rights movement that involved so many other passionate, dedicated activists and advocates during a time of enormous urgency for their communities — the period, Kemper says, that extends from the time of the bathhouse raids to formal legal equality.

“There were many people involved in the fight in all areas. Much of it was fueled by the enormous passion and energy fomented by the HIV/AIDS movement. People meant it when we said silence equals death. We knew that the closet would kill people, and it was killing people. We fell into that symbiotic energy. We felt we had to fight on all fronts.”

Speaking truth to power

After a career as a non-profit leader, Alison Kemper now researches the impact of social and environmental issues on business strategy at the Ted Rogers School of Management. Her life is deeply interwoven with LGBTQ2S+ rights movement in Canada.

Pride month is a time to celebrate diverse gender and sexual identities and expressions, as well as recommit to the fight for equality and freedom from discrimination. Recent years have seen a rise in homophobia, in particular towards the trans community. The struggle is still far from over.

Kemper encourages young people to volunteer with grassroots community organizations to gain an important understanding of the issues and to get familiar with how advocacy can lead to real-world policy changes at all levels of government.

“Kids need to know that they are precious, no matter how they identify. They will not be free of battles and their friends need to be their allies.”

Related stories: