My Two Days with the Bertauds

By: Diana Petramala

(PDF file) Print-Friendly Version Available

October 18, 2019

The Centre of Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) invited Alain Bertaud, Senior Research Fellow at the Marron Institute at New York University, former Principal Planner at the World Bank and author of the book “Order without Design” to Toronto to speak at three events over the course of two days. I was fortunate enough to attend all three talks given by Alain, and also to spend a morning touring the Financial District and King West area with Alain and his wonderful wife, Marie-Agnes, his collaborator in urban planning.

Alain Bertaud’s discussion at all three events focused on the key theme of his book “Order without Design”:

- It is people that shape cities, not urban planners.1

He believes that cities are largely labour markets and that the market (or economic forces) will drive their development, no matter what regulations are in place. Regulation, if not well thought out, can add additional costs and cause unintended consequences, such as (ironically) contributing to deteriorating housing affordability and congestion.

The idea that an understanding of economics and how markets function can help planners make better, more informed decisions was corroborated by Matthias Sweet (Associate Professor at the School of Regional and Urban Planning at Toronto Metropolitan University), and Russel Matthew (Principal at Hemson Consulting), Alain’s fellow speakers at CUR’s event on Monday, September 30th.

(The presentations and a video of the event can be found on our website. We will also be making Matthias Sweet’s remarks available in a separate blog as they were quite insightful.)

At an event hosted by the Toronto Association of Business and Economics (TABE) on October 1st, Alain was joined by Paul Waddell, an urban data scientist from Berkley University. Here, Paul illustrated how he is attempting to put Alain’s theory into practice through the development of the UrbanSims model – an analytical tool for assessing the impact of urban planning policy decisions within an urban metropolis.

(Alain also presented at a dinner meeting of Lambda Alpha International’s Simcoe Chapter.)

The two days of events and time spent with the Bertauds taught me a lot and here is what I learned:

Cities (metropolises) are integrated labour markets, and the job of an urban planner is to make sure these markets functions well

While urban planners want to design cities as nice places to live in, in reality cities are a place where businesses come to cluster and people come to look for jobs. Alain argues that the best way to support the development of well functioning regional labour markets is to:

- Make sure everyone has the opportunity to access a variety of jobs within an hour commute; and

- Make sure all households can find accommodation that would not cost more than 35% of their income.

As such, the best thing urban planners can focus on is investing in transportation infrastructure, especially out to where land is available for affordable housing.

Markets will ultimately shape the design of cities and certain regulations can be counterproductive

In his work, Alain argues that markets, not urban planners, shape cities using two examples:

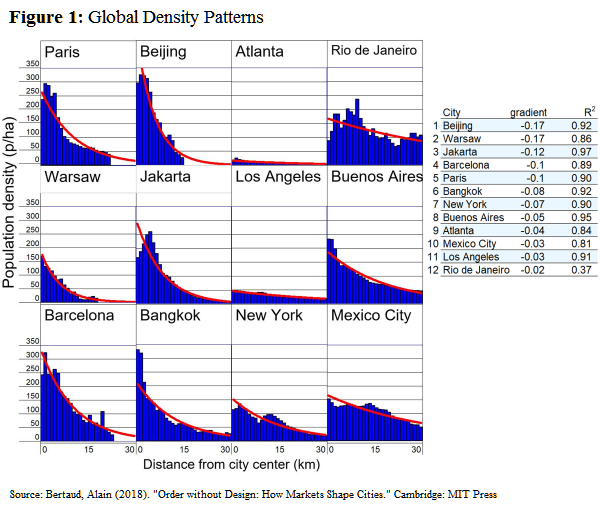

- Density patterns are similar across global major cities, despite differences in regulation. Alain uses charts of nine cities – three in North America, three in Asia and three in Europe (see Figure 1). They show the change in density as you move further from the central business district (CBD). While these cities have different regulations, they ultimately follow the same pattern as a result of economic forces – density is highest near the CBD and lessens as you move further away from downtown.

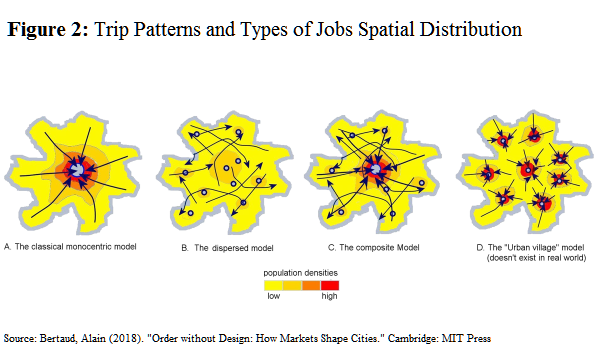

- Designs laid out in master plans rarely translate into reality because, despite the best efforts of planners, these plans go against the reasons cities get built in the first place. Alain highlights “four spatial” patterns of urban development (see Figure 2). The first pattern is the predominant outcome for major cities. As seen in the first pattern, firms like to cluster and households like to move to where housing is affordable. Jobs cluster in the CBD and the labour force mostly commutes into work. The fourth pattern, “urban villages” (or complete communities in the jargon of urban planners) projects a city with a number of nodes where households live, work and play. In Alain’s words, this is the pattern you most often see in master plans, but rarely in reality since it largely goes against why and how cities grow. “Urban villages” are a planner’s dream, but not an urban reality.

Russel Matthew reinforced this view by referring to the development in the King West/Fashion District area. The City of Toronto had zoned streets along King West for maximum heights of 12 storeys, but the market ultimately won, as buildings are being built with much higher heights. For instance, the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) building at King Street West and Spadina Avenue is being replaced with a 49-storey development.

Urban planners must take market forces into consideration when designing policy

Alain argues that urban planners need to understand market forces in order to design effective policies. My favourite quote of all three events was this…

“If there is an outcome you don’t like, you can’t change it if you don’t understand it.”

Quite often regulations are inefficient or counterproductive because the impact they will have on the market is not well understood by those designing them. In many cases, poorly designed regulations only add to the challenges that comes with rapid population growth, such as deteriorating housing affordability and congestion. A growing body of research has been published recently linking these challenges to ineffective regulation, supporting Alain’s views.

Yellowbelt zoning is counter to achieving the city of Toronto’s affordable housing goals

Okay, Alain did not exactly say this. However, he does argue that policies that restrain density and housing sizes, such as those found in the Yellowbelt zoning, are often inefficient. In his presentations, he argued that both urban planners and economists should not play a role in determining what densities in a city should look like. Alain is neither pro-density nor pro-urban sprawl, and had positive things to say about both in our conversations. He just thinks it is a decision the market should be able make, and that households should have greater choice.

The same goes for policies that aim to regulate the size of housing. In large cities, households make trade-offs between the amount of housing they consume, how much they pay for housing and commute times. Living near the central district allows households to access amenities and jobs within short commutes, but they also have to be prepared to live in small housing spaces, unless they are affluent. Households who choose sprawl get big more affordable housing, but have to commute longer into the CBD. Households should have choice. Outcomes of those choices will only be efficient if the prices are not distorted by regulation.

The role of urban planners and economists should be to attempt to forecast densities so that they can be prepared to provide the appropriate infrastructure in areas where densities are expected to increase. Of course, forecasts can be wrong and any plan must leave room for flexibility.

Alain acknowledged that, historically, regulation has had a role to play in urban planning. Zoning was largely used to control density and separate housing and employment districts to avoid negative externalities. However, those externalities have become less and less over time, so less regulation is now needed.

He points out that regulating densities rarely lead to outcomes urban planners are trying to achieve, such as affordable housing and shorter commutes. In fact, denser areas tend to be more expensive and more congested.

Design does matter

Touring a small part of downtown Toronto with the Bertauds helped me remember that it is a terrific city and does do a lot of things right! I also had the opportunity to see Toronto through the eyes of an urban planner/architect rather than as an economist.

As the Bertauds gawked at the design of Toronto’s buildings and its spacious, well-thought out sidewalks, I began to understand that design does matter. They enjoyed the quality of the buildings and the underground Path in the Financial District, which they felt provided a nice realm for public space. They really enjoyed how the building designs and restaurant patios flowed onto the street and were largely integrated as part of the streetscape along King West, between Spadina Avenue and Portland Street.

Some food for thought on affordable housing

My heart and soul belongs to affordable housing research and the feedback loop to economic growth – and so I made sure to ask lots of questions about how cities could attain affordable housing. This conversation left more questions than answers, to be honest.

Alain is cautious of inclusionary zoning (a land-use tool that allows a city to negotiate over density to ask for more affordable units). He argues against its use, as these units can come at a hefty cost to those who buy or rent market units, not just in the buildings for which inclusionary zoning is applied but more broadly across the housing markets.

This leads to the conclusion that there needs to be more economic research on the winners and losers (‘pareto efficiency’ in economist jargon) of affordable housing policies and into the most optimal way to provide more inclusive housing in rapidly growing cities.

Conclusion: planners and economists should learn to work together

In an online interview with Alain Bertaud, Paul Romer (last year’s Nobel Laureate in Economics) joked that economists and urban planners / architects are known to be mortal enemies.2 However, Bertaud argues that the professions have very different objectives and that they both have important knowledge to contribute to city building. The debate should not focus on design OR markets, but on how cities have to do a better job at bridging and integrating the two in planning and economics departments.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Alain uses the term "city" as referring to urban metropolises or regions.

[2] The full interview between Alain Bertaud and Paul Romer is available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYOpjXg0Amc

Diana Petramala is Senior Researcher at Toronto Metropolitan University's Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.