Associate Professor Baruch Zone Reflects on Teaching Legacy at DAS

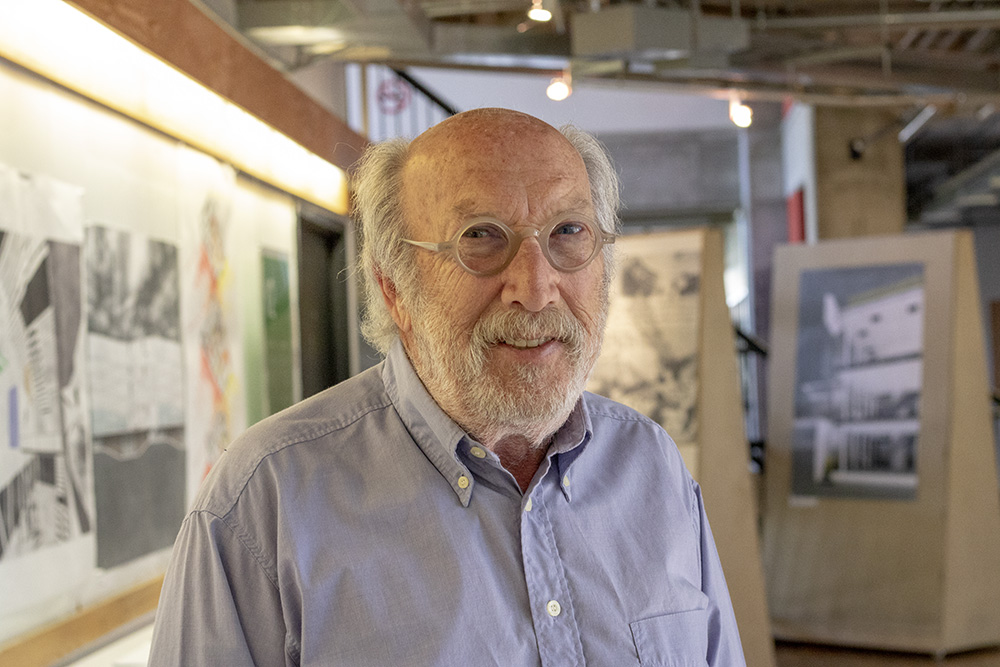

After teaching at the department for over 35 years, Professor Baruch Zone is retiring. We spoke to Baruch about his journey from being a registered architect in the seventies and opening his own private practice in 1980, to teaching at the department. Baruch practiced architecture while a CUPE instructor from 1985-1999 up until his appointment to the RFA.

Highlighting the design of the Ministry of Revenue building in Oshawa, the most energy efficient building in Canada at the time, Baruch remarks:

“In terms of energy efficiency and from a basic design perspective, the building respects notions of heat gain and heat loss conditions on different elevations. It is the first building in Canada to make use of a sheet metal vapour barrier throughout the building. The idea of keeping the wall assembly protected from the interior environment was groundbreaking at the time. The building’s atrium space is dovetailed into heating, ventilating, and reclaiming heat before it’s exhausted for fresh air. The project is very technical in its approach and I brought my knowledge of that to the department.”

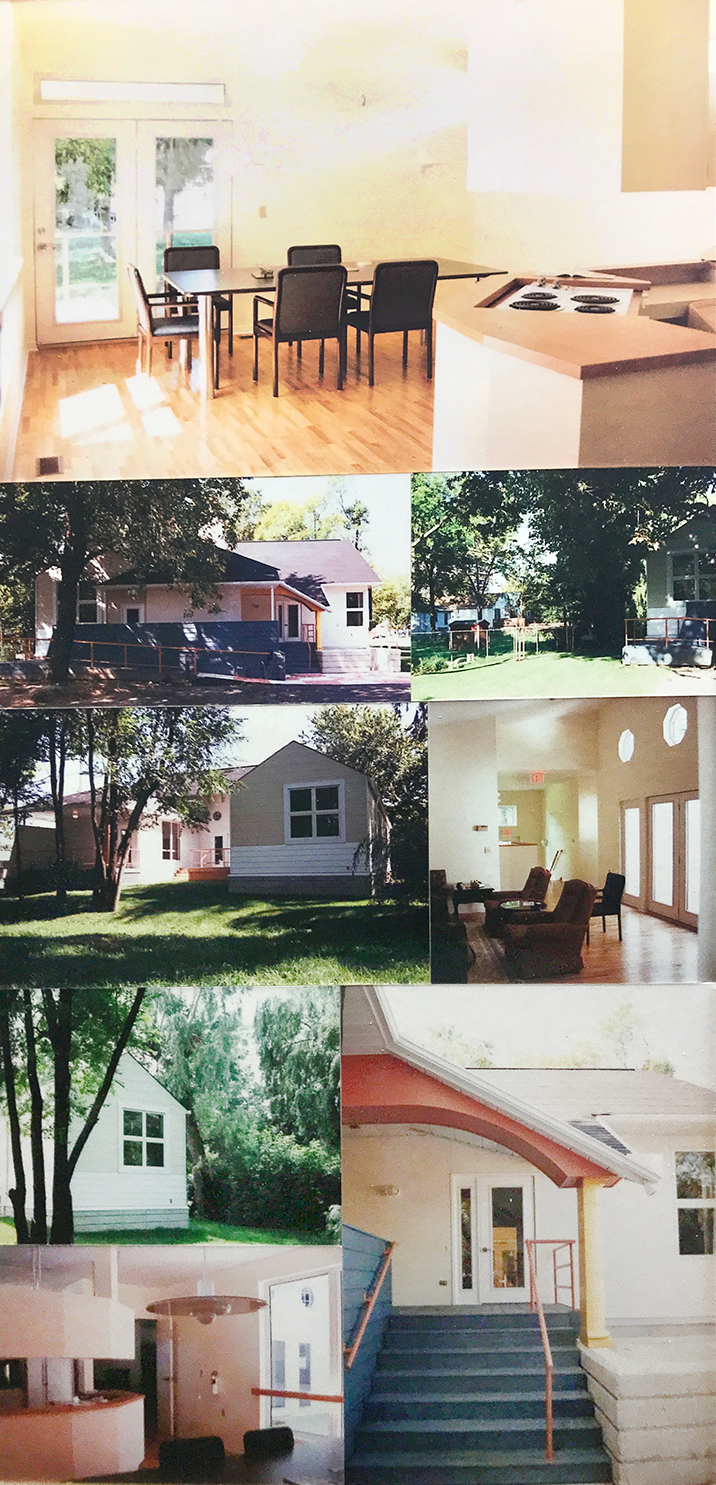

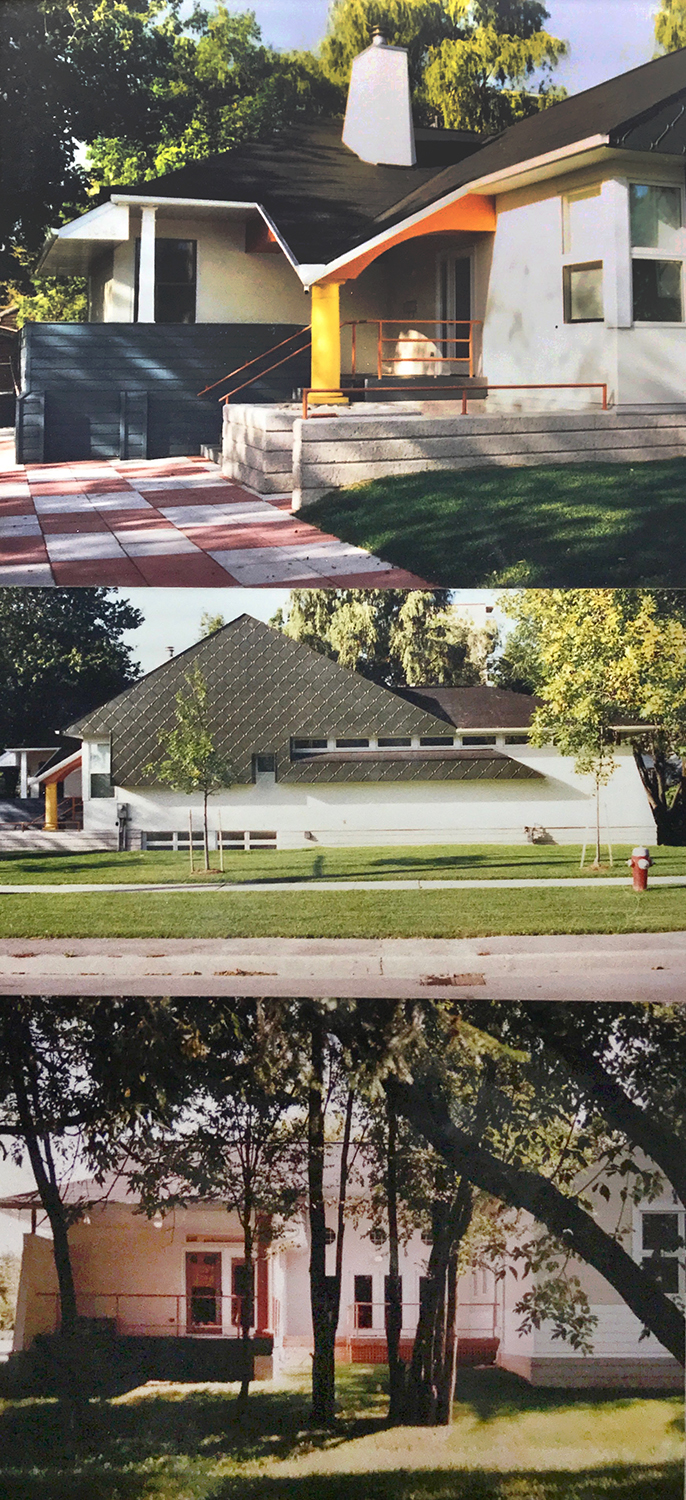

Baruch’s extensive work on governmental projects includes accessible housing and care facilities, from social housing with barrier-free accessible units to group facilities for the rehabilitation and support of those living with the effects of acquired brain injuries.

“Along with the client, we agreed to deinstitutionalize these facilities as much as possible to create or recreate a comfortable and inviting living environment–we were tasked with making the unconventional conventional.”

It was while working on the PHABIS (Peel Halton Acquired Brain Injury Services) facility designed in 2000 for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Ministry of Long-Term Care, that he first collaborated with associate professor and architect Yew-Thong Leong.

The needs of the project included being mindful of creating a safe living and learning environment for brain injury survivors by considering scale, as well as minimizing auditory and visual stimuli. The two architects agreed that Baruch would lead the design of the facility while Yew-Thong’s practice would develop the technical documents and production with his input. Graduate student Tony Diodati, employed by Yew-Thong at the time, took on a significant part of the work as the project architect.

Yew-Thong fondly reflects on his time on the project, underscoring Baruch’s empathy for his clients:

“The residents by and large are quite independent… But occasionally their symptoms would kick in and accommodations would need to be made for spaces where they could safely work through their symptomatic phases… The community kitchen was a place where residents could cook light meals or snacks for themselves or each other, and something Baruch put a lot of care and attention into… We used a special insulated polycarbonate panel envelope system in the outdoor activity space–Baruch is technically skilled and a good designer who was always on the lookout for new innovations.”

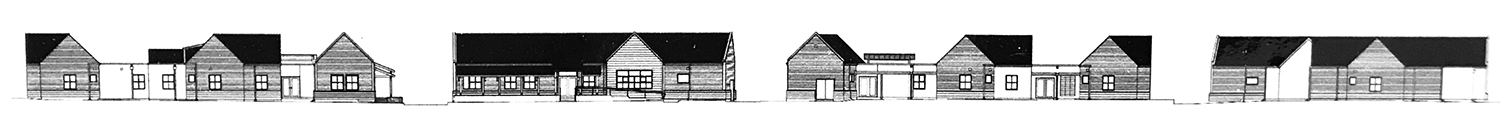

HIAPH House (Head Injury Association of Peel and Halton) Rendering

HIAPH House

HIAPH House

Elevation Drawings of HIAPH

The approach Baruch adopts to his work is a humble one: “We could never really break into the ‘champagne projects’, and we didn’t compromise on ideals - we treated each project with honour and respect - we didn’t regard ourselves as heroic in any way.”

Good design for Baruch means doing away with a repetitive template and focusing on program and site analysis - what he designates as the hallmarks of a healthy architectural process in terms of design development, “It was always important in the end to meet not only the client’s expectations but also our own. We never worked our way backwards in order to justify design decisions.”

Baruch decided to not maintain a practice when starting his tenure track position at the department in 1999, and teaching proved to be a rewarding and enriching experience: “There’s this kind of joy that exists when things click in a studio-based culture. You can pick up on all the energy that’s brought into a project which can be discussed on a multitude of levels that is driven by both theoretical principles and decisions based on subjectivity. It’s a unique experience that you may not get in other courses, where student work is driven by objective learning goals, shall we say. I feel lucky to get to see a variety of processes and ask ‘How did you arrive at that?’ - you’re experiencing the building blocks of architectural thought.”

Having taught ASC 622 for a decade and a half, where students learn to prepare construction documents, Baruch describes the class as an “architectural siv”, where students’ presuppositions about how to design are challenged:

“Everyone thinks they can design. But it’s actually working it out in the end, and tackling it from a building science perspective, putting together that 50% of architecture you base your fees on - ‘where the rubber meets the road’ - is really felt… Everyone can design, not everyone can build.”

“Many of our students in the industry right now owe their current knowledge base to Baruch’s class on construction documents.”

For Baruch, small buildings have big appeal. From wilderness survival cabins to public washrooms, they are crucial to our lives; but they often don’t get their due. When Baruch began teaching ASC 856, he celebrated the infinite potential of small structures. “This kind of design takes them back to the scale of first year, but with all the knowledge they now have.” The result? Fantastically creative projects that challenge the definition of what a small building can be–from an adventure playground that hangs from Toronto's Bloor viaduct, to body armour that can be transformed into an emergency shelter.

Baruch would also encourage students to look at the intersection of architecture and pop culture: “We’d have an entire class on ‘Googie Architecture’ in LA…drive-in restaurants, white towers, hamburger joints, we’d look at the branding, signage, Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas… How do you make a statement when people are passing you by at 60 km/hr?” Students explored themes around youth culture, suburbia, the automobile, and freedom, asking fundamental questions like: “What makes a building?” Does it need four walls? A roof? Can it imply a roof? Is the Parthenon still a building or the Acropolis if it doesn't have a roof? You can envision the roof, right? How do you represent or define things spatially?... What are the differences between Habitat 67 and favelas in Rio de Janeiro? The difference is economics, and technology–but they’re both small buildings when you break them down. They follow principles of modularity and shared ownership - the roof of the adjoining unit, the outdoor spaces, for example.”

Baruch underscored the happiness and recharge he would get from student work, as well as constantly redeveloping the Small Buildings course which would be constantly shifting to maintain contemporary relevance: “I would include things that became architectural news, but instead of doing Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, I would do the sculpture inside by Richard Serra - a building within a building. We would look at how the sculpture engages with the acoustics of the space–it’s so playful…”

When speaking to his pedagogical approach, Baruch underscores the aim to “understand what students were doing, and why they were doing things that didn’t seem to fit the rubric of what they were doing…”

Baruch leaves behind a legacy of care and attention, always encouraging students to think things through in original terms, even when it comes to conventional projects. He emphasises the importance of constantly questioning and redefining what the built environment means.

“One of the secrets of architecture is to develop a big idea, then you don’t have to worry about accessorising it with things that may or may not work. You don’t pile it on. I would ask students: Why would you do this? Would you lose anything if we made this disappear? Let’s make it easy to represent - let’s break this down, like a precis of their design. Can you take out every third word and still have a sentence, a paragraph, and have the meaning stay exactly the same? Can you clarify certain aspects so it falls in line with your intent? Things can be hidden or brought to life depending on what you want to achieve.”